The Last Soldiers of the English Civil Wars

‘They say I am the last of them alive; they say I am the last roundhead’, begins the fictitious Blandford Candy in the novel The Last Roundhead by Jemahl Evans (Holland House Books, 2015). The real identity of the last surviving civil-war soldier will probably never be known for sure. The last surviving member of the Long Parliament was Sir John Holland, who sat for Castle Rising in Norfolk, and died aged 97 on 19 January 1701. We now know that quite a few of the war’s officers and soldiers outlived Sir John. Richard Cromwell, the former Lord Protector died in 1712, yet his military service is uncertain and may have been limited to a brief spell in Fairfax’s lifeguard in 1647. Mark Stoyle considers the last surviving field officer in the army of Charles I was Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Neville who also died in 1712. The last Welsh royalist officer that we know of who received a pension was Captain Richard Vaughan of Llanwrst, Denbighshire. A previous blog by Lloyd Bowen showed that Vaughan was blinded having been shot in the face, but found support among the poor knights of Windsor during the 1660s Vaughan’s portrait was drawn by Sir Peter Lely at a St George’s Day ceremony at Windsor. He did not die until 5 June 1700, aged eighty. But what of the rank and file who made up the armies on both sides? ‘Welsh Thomas’, conscripted for the royalists in Carmarthen, claimed in 1717 to have been captured at the siege of Gloucester in 1643 [Mark Stoyle, ‘Memories of the Maimed: the Testimony of Charles I’s Former Soldiers, 1660-1730’, History, 88:290 (2003), p. 207]. In counties where good records survive, our team’s research is demonstrating that significant numbers of maimed and wounded soldiers survived into the eighteenth century…

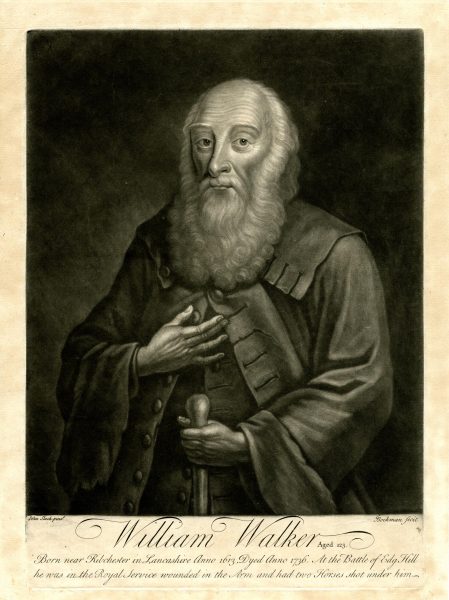

William Walker of Ribchester, Lancashire. Mezzotint by John Slack from a portrait by Gerhard Bockman (© The Trustees of the British Museum, reproduced under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence).

Some historians have considered that the last civil-war soldier was William Walker of Ribchester, Lancashire (1613–1736). Walker fought for Charles I at the Battle of Edgehill in 1642, where he was wounded in the arm and had two horses shot under him [Charles Carlton, Going to the Wars (London, 1994), p. 349; Peter Young and Wilfrid Emberton, The Cavalier Army: Its Organisation and Everyday Life (1974), p. 144. Walker has a portrait in the University of Leicester’s Fairclough Collection, but not digitised yet]. Yet no petition for a pension survives for him among the Lancashire quarter sessions. Walker attained some contemporary fame by appearing as the subject of a portrait by Gerhard Bockman and a later mezzotint by John Slack. The Ribchester parish register has a burial entry for 16 January 1736 which states ‘William Walker, a Cavalier aged 122’ [Lancashire Archives, PR2905/1/2]. The Anglican clergyman-antiquarian, Thomas Dunham Whitaker noted in 1823, that ‘At the Church of Ribchester was interred, in all probability, the last survivor of all who had borne arms in the war between Charles I and the Parliament … How long he retained his faculties I do not know; if nearly to the close of his life, he must have been a living chronicle, extremely interesting and curious’ [T.D. Whitaker, History of Richmondshire (London, 1823), vol. ii. p. 465]. The claim that Walker lived 122 years is suspicious as it far exceeds the Guinness World Record of 116 years for the world’s oldest ever man. But it remains possible that Walker had fought at Edgehill and was around 110 when he died.

William Hiseland by George Alsop (image from Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Hiseland).

Another, more believable claimant is William Hiseland of Wiltshire (1620–1733). His tomb’s inscription at the burial ground of the Royal Hospital in Chelsea stated that he was born on 6 August 1620 and died aged 112 on 7 February 1733. Hiseland claimed to have fought at Edgehill in 1642 and after a long career in soldiering, with the Royal Scots at Malplaquet, despite being 89 years old in 1709. Hiseland was rewarded with a place at Chelsea Hospital until he became an out-pensioner following his marriage at the age of 100 in 1720. He sat for a portrait by George Alsop in 1730, in which a sturdy appearance is strikingly fashioned for a man of 110 years of age.

Claims of advanced age were difficult to verify for certain in this period, because of the relative absence of portable, authoritative life documents. Individuals outside the parish of their birth might make exaggerated claims without the fear that sceptics would travel to their home parish to consult the baptism register. Indeed, evidence from our petitions suggests that people of advanced years did not always know their precise age.

With our material for Wiltshire and Lancashire still to be uploaded, it is currently not yet known if Walker or Hiseland benefitted from county welfare payments because of their civil-war service. It is quite possible they did, because although the 1662 Act to relieve royalist maimed soldiers officially expired in England and Wales in 1679, in many counties collections for them continued. For example, the Thirsk Sessions in Yorkshire, with the advice of the Attorney General, ruled in October 1688 that although the 1662 Act had expired, the Elizabethan Act of 1601 remained in force. This enabled Yorkshiremen to petition well beyond 1700. The last surviving petition for the North Riding of Yorkshire came from Robert Wrigglesworth of Little Thirkleby in April 1701. Fittingly, he claimed to have served in Sir Robert Strickland’s regiment, the first regiment to be raised for the King, in May 1642.

Our last surviving petition from the West Riding of Yorkshire came from John Genn, who claimed in January 1709 that he was 82 years old and had served under Sir Francis Fane, royalist governor of Lincoln. Genn’s petition is among eight surviving petitions from the West Riding that all date after 1700. Six of these petitioners resided in Genn’s home parish of Aston, just south of Rotherham, and two in the neighbouring parish of Treeton. The marked concentration of these last petitions in two adjacent parishes, and the supporting signatures and marks beneath them suggest the influence of a local network of parish officers and neighbours pushing these elderly men forward. Three of their petitions were signed by Samuel Trickett, rector of Aston from 1694 to 1712. Trickett used the parish register to certify that one of them, Francis Petty, was baptised in 1623, making him old enough to have served in the wars. The clustering of these last petitions may also have been due to Aston having been the seat of Sir Francis Fane (d. 1680), under whom four of the petitioners claimed to have served. There is a strong likelihood that these eight men were all known to each other, suggesting something of a network of veterans similar to the Devon tinners discussed by Mark Stoyle. These men were sharing their memories of civil war and receiving community support over 60 years later. One wonders how many similar networks elsewhere in the country persisted into the eighteenth century.

The first of these eight men was Francis Jenkin of Aston, who received a pension of £2 per annum after he petitioned the Sheffield Sessions on 16 October 1700. He claimed to be ‘now Four score years ould & upwards’, and that he was a ‘souldier und[e]r King Charles ye first’ under the command of Major ‘Gore’ (possibly Major William Gower) at the siege of Hull in 1643. In 1701 two more petitioners from Aston, Anthony Davy and Richard Kelke, both secured pensions of £2 per annum having petitioned the sessions at Pontefract and Doncaster respectively. Davy claimed to be 84 years old. Both men claimed to have been among Fane’s Doncaster garrison before their capture by Lord Fairfax at the Battle of Selby on 11 April 1644, and that they both suffered imprisonment thereafter in ‘Reasor’ (likely Wressle Castle).

George Inkersell of Aston secured a pension of £3 per annum when he petitioned the Barnsley Sessions on 5 October 1704 that he was aged ‘ninety years & upwards’, and that he had been no further than ¼ mile from home in two years, reassuring the justices ‘my time cannot be long in this World.’ His petition was endorsed by Trickett, along with the churchwardens and a string of neighbours. In January 1706, William Walker in neighbouring Treeton secured a pension having petitioned the Doncaster Sessions that he had been wounded serving under the command of the martyred royalists John Morris and Michael Blackburne in the Pontefract Castle garrison during 1648–9. William Hilton, also of Treeton secured a pension of £3 per annum in August 1708, having petitioned the Rotherham Sessions that he too had served under Fane as a soldier ‘to his sacred Majesty K[ing] Charles the Martyr of ever blessed Memorie.’

Turf House, Steel, Hexham, the home of Henry Norton (photograph by Andrew Hopper by permission of the owners Andrew and Jackie Middleton).

An even later petition survives in Northumberland: that of Henry Norton of ‘Turfe House’ in the hamlet of Steel, in Hexham parish, who, aged ‘near upon 90 years’, petitioned the midsummer sessions at Hexham in July 1710. In his petition, Henry claimed to have borne arms for King Charles I ‘of blessed memory’. Henry’s three sons had left to join ‘the Queen’s service’, and were probably fighting in Europe under the command of the Duke of Marlborough. This, he claimed, had left him in ‘miserable and deplorable circumstances’, wanting friends, and utterly dependent upon ‘the charitable help of well-disposed persons’. For good measure, he added that he had always ‘been of a good life & Conversation & a True Member of ye high Church of England’. This was a calculated appeal to the Tory JPs on the county bench and it was successful. On 12 July 1710, the JPs ordered the churchwardens and overseers of Hexham to pay Norton eight pence per week towards his maintenance. This was comparable to a pension of nearly £2 per year, and worth the effort to obtain in order to enable Norton to survive in his last years. We do not know how much longer Norton lived, or whether he witnessed the recruitment of 200 Northumbrians from his home neighbourhood for the Jacobite forces in 1715. Less than four miles northeast from Norton’s home was Dilston Hall, the seat of James Radcliffe, 3rd Earl of Derwentwater (1689-1716). A grandson of Charles II, Derwentwater was beheaded on Tower Hill on 24 February 1716 for leading the Northumbrian rebels and was buried in the family chapel at Dilston.

The last civil-war pensioner for whom we currently hold firm evidence was William Leaver the elder, a pinmaker of Aylesbury. William petitioned the Buckinghamshire Sessions at Aylesbury in July 1704, that he had been in receipt of a maimed soldier’s pension of £2 per annum for several years. A separate memorandum confirmed William had served ‘his most sacred Maj[es]tie King Charles the First’. William requested successfully that his pension be augmented to £4 per annum because he was ‘fallen almost Blind whereby he is rendered very helpless poor’. He signed a receipt with his mark on 27 July 1704. His pension was increased further; by 1716 William had been receiving £6 per annum for several years. In October 1716 his pension was enlarged to £8 per annum. William petitioned again, in July 1717, for a further augmentation now that he was ‘aged 100 yeares or thereabouts’, and ‘quite blind’. The Justices raised him to £10 per annum. In January 1718 his pension was increased yet again to £12 per annum, on account that he was ‘altogether unable & uncapable to help or support himself without the assistance & helpe of some person or persons to Assist him.’ The clerk of the peace noted the special nature of this payment, at a time when ‘the number of Pentioners of this County have encreased’. William did not collect this for long because on 24 April 1718 the county treasurer was ordered to pay William’s son John Leaver 40 shillings for the costs John had incurred in his father’s burial.

The last known war widow of the Civil Wars to receive money from a county treasurer was Mary, widow of William Hobbs of Chepping Wycombe. She was awarded 10 shillings as the last quarter of her late husband’s pension by the Buckingham Sessions on 11 April 1700, despite there being no legal basis by then that entitled her to relief. In 1694 William had been awarded a pension of £2 per annum for his service under Charles I, and his later service in the Anglo-Dutch Wars, with his petition supported by a certificate from the mayor of Chepping Wycombe.

A comparison with the American Civil Wars reveals an even longer period over which military pensions were provided. The last widow of an American Civil War veteran was Gertrude Janeway (1909–2003). She married John Janeway, a veteran of the 14th Illinois Cavalry in 1927 and received a pension of $70 every two months until her death. Janeway was outlived by Irene Triplett of Wilkesboro, North Carolina, the last pensioner of the American Civil Wars. Irene was born in 1930, the daughter of Union veteran Moses Triplett, who died in 1938, having married a woman 50 years younger. Irene passed away on 31 May 2020, having long collected a pension of $73 per month from the Department for Veterans Affairs because of her father’s civil-war service. Individuals such as Janeway and Triplett were the inspiration behind the prize-winning novel by Allan Gurganus, Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, first published in 1989. The individuals in this blog should remind us that the human costs and living consequences of civil war do not end when treaties are signed, republics are forged or kings are restored. They remain with us generations, even centuries later.