‘Wounded att Stampford Worke’: Two Devon ‘Tinners’ Recall their Wartime Service

The horrors of war are known to forge strong bonds of friendship and reinforce existing ones; friendships that do not end once the fighting is over. Here, Mark Stoyle examines the petitions of two men recruited from the same Devon parish and who served in the same regiment, revealing that their recollections of royalist service reveal strikingly significant similarities…

After the Restoration, two former Royalist soldiers from the remote Dartmoor parish of Lustleigh petitioned the Devon JPs for pensions to support them in their declining years, both men testifying that they had been wounded in Charles I’s service during the Civil War. The first petition was that of Laurence Elliott, whose occupation was left unspecified, the second that of Robert Spray, a husbandman. Although the petitions are in different hands, there are hints that there may have been personal or textual interconnections between the scribes who penned them as both petitions refer to their subjects being now grow ‘old … and decrepped’: a slightly unusual formulation. The stories which the two documents tell possess a number of striking parallels, moreover. Thus Elliott’s petition states that he had served in the king’s western army ‘under the commaund of Bartholomew Gidley, Esquire, Captain of the Tinners’, while Spray’s petition states – rather more expansively – that he had served ‘under … Bartholomew Gidley, Esquire, Captain under the command of Sir Nicholas Slanning, K[nigh]t, Colonell of the Tinners’.

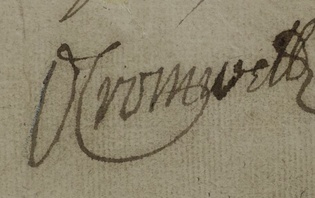

Slanning and Gidley were names to conjure with in post-Restoration Devon. Sir Nicholas Slanning had been the original commander of one of the five ‘Old Cornish’ regiments which had conquered South West England for the king during the summer of 1643: a regiment which had been largely recruited from among the ‘Tinners’, or tin-miners, of Devon and Cornwall. In July 1643 Slanning had been mortally wounded at the storm of Bristol. Sixty years later, his name – together with those of other key officers who had died in the king’s service in the West – was still remembered by local loyalists in the mournful distich: ‘[Gone] the four wheels of Charles’s Wain: Grenville, Godolphin, Trevanion, Slanning slain’. The phrasing of Spray’s petition strongly suggests that he had served under Slanning’s personal command – but it is also conceivable that he had joined the Tinners regiment after the death of its most famous colonel, and that he and/or the scribe who drew up his petition had subsequently taken the tactical decision to include Slanning’s name in the document in order to furnish it with added lustre. What is crystal clear is that both Elliott and Spray had served in the company of Captain Bartholomew Gidley, of Winkleigh: a Royalist gentleman who had fought with distinction in the Tinners regiment throughout the war and who had been appointed to the Devon Bench after the Restoration. Indeed, Gidley himself was one of the four JPs who appended their signatures at the bottom of Elliott’s petition and affirmed that they believed its contents to be true: striking evidence of the fact that the bonds between some former Royalist officers and their soldiers had continued to endure long after the Civil War was over.

That Elliott and Spray later testified that they had served under the same company commander in the same regiment strongly suggests that the two men had joined up at the same time, and it is fascinating to note that their petitions also show that they had gone on to be wounded in the very same engagement: the assault on the Parliamentarian fort of Mount Stamford, near Plymouth, in late 1643. Following the Royalist capture of Bristol that summer – an event which had seemed, to many, to herald the imminent collapse of the Parliamentarian cause – the king’s western army had marched back to Devon in order to reduce the remaining Roundhead strongholds there. Exeter was taken on 7 September and Dartmouth a month later, and by mid-October the king’s victorious forces were closing in on Plymouth: by now the only place in Devon and Cornwall which continued to hold out for the Parliament. Having surveyed the town’s defences, the Royalists quickly decided that Mount Stamford – an isolated earthwork fort which the Parliamentarians had thrown up on a peninsula on the other side of the Catwater, and which was thought to command Plymouth Sound – was the key to the entire position. Accordingly, they made their dispositions and prepared to move into the attack.

On 21 October the Royalists began to erect earthworks of their own to the south of Mount Stamford, and over the following days a series of bitter skirmishes took place as the defenders tried to drive them off. It was not long before the Cavaliers were ready to launch their final assault. ‘The 5 of November, in the morning betimes’, wrote an anonymous Royalist eyewitness, who later composed a vivid account of events, ‘our ordenance begone to play upon Mount Stamfort’. The barrage continued all that day and the next morning, he went on and ‘all this whille wee stod in redinesse to fall on … being 3 regiments of foote and 5 trupes of horse’. Neither the eyewitness nor any other contemporary source names the three Royalist infantry regiments which took part in the assault, but the petitions of Elliott and Spray make it clear that the Tinners regiment was one of them. ‘The word beeing given, which was “victory”’, the eyewitness goes on, then ‘our foote marchet up [to the enemy work] … when, beeing together, wee made 3 shouts which made the hilles ring’. The Royalist forces now moved into the assault, and, after a hard-fought struggle, finally captured Mount Stamford. Among the many soldiers injured in the fighting that day were Laurence Elliott, whose petition attests that he was ‘wounded … att Stampford worke against Plimmouth’ and Robert Spray, whose petition likewise sorrowfully records that he ‘tooke great hurt … at the takeinge of Stampford worke against Plimouth’.

The fact that two men from Lustleigh – a little moorland parish whose entire adult male population in 1641-42 was only around 50 – can be shown to have been wounded in the same engagement is revealing. It reminds us that, because the regiments of the Civil War tended to be raised – initially at least – from quite tightly-contained geographic areas, it was possible for individual parishes to suffer very high casualty rates when ‘their’ regiments took part in especially bloody actions. The parallel journeys which Elliott and Spray made – from the peace of Lustleigh to the hell of the siege of Plymouth and back – also makes us curious about their own relationship. One cannot help wondering whether the two men were friends and whether they continued to meet up to discuss their wartime experiences long after the conflict was over – just as we know that the men of the nearby parish of Drewsteignton were to continue to meet up to discuss their wartime experiences in the local pub in the wake of another, still greater conflict, three centuries later.

A final question raised by these intriguing twin petitions is why the only wartime engagement which either of them mentions by name is the fight at Mount Stamford – even though Spray’s petition proudly declare that he had fought ‘in many battles’ on the king’s behalf? An obvious answer would be to suggest that both men’s military careers had been terminated by the wounds they received in November 1643, and that this in turn meant that the fight at Mount Stamford was the obvious ‘peg’ on which to hang their petitions. Matters are not so clear-cut, however, for, in point of fact, both men’s testimonies affirm that they had served throughout the conflict: ‘from the beginninge to the end of the said warr’ in Elliott’s case, and ‘to the end of the said warrs’ in Spray’s. The Civil War in Devon did not end until 1646, so – unless we presume that the petitions claimed that Elliott and Spray had fought throughout the entire war as a simple matter of form, as a method of putting their loyalty beyond doubt – there must have been another reason for the petitioners themselves, or for the scribes who wrote on their behalf, or both, to have laid particular emphasis on the fact that the former soldiers’ wounds had been received at Mount Stamford.

It is important to remember here, perhaps, that in November 1643, the Royalists had celebrated their successful assault on Mount Stamford as a glorious feat of arms: as a victory which would lead, ineluctably, to the surrender of Plymouth itself, and which would thus permit the remarkable string of victories which the king’s western army had achieved over the preceding six months to be crowned with final, definitive, triumph. Yet, in the end the Cavaliers were to be sorely disappointed. Cannon placed at Mount Stamford, it transpired, were unable to prevent Parliamentarian ships from entering Plymouth Sound and supplying the garrison with ammunition and food. As November passed away into December, moreover, the Royalist besiegers suffered increasingly heavy casualties as they strove, ineffectually, to breach the defences of the town itself. On Christmas Day 1643, the siege was lifted, and although the Royalists made many more attempts to capture Plymouth over the following two years they were invariably repulsed with heavy losses.

The Tinners regiment – including Captain Gidley’s company – is known to have taken part in a number of these fruitless operations, so it seems probable that Laurence Elliott and Robert Spray did so, too. Yet it is easy to understand why – when the two old soldiers and their local backers were pondering how best to ‘spin’ their petitions to loyalist magistrates after 1660 – they might well have decided that it would be more politic to highlight the injuries which the men had received during the brief moment of Royalist triumph before Plymouth in November 1643 than to itemise any further ‘hurts’ they may have suffered during the long, sad series of reverses before the same town which followed. Civil War petitions like the two discussed above not only provide us with vivid insights into the lived experience of the conflict itself, in other words, they also provide us with tantalising hints of the myriad ways in which individuals’ memories of that conflict could be subsequently sorted, sifted and deployed – both consciously and sub-consciously – in support of their own present purposes.