‘Meamed and Lamed’: Approaching Civil War Petitions through the Lens of Disability History

We have published several blogs on what the documents on Civil War Petitions can reveal about the medical history of the Civil Wars but so far we have said little about what the petitions reveal about disability history. Therefore, in this week’s blog, Liv Bennison uses the petitions to uncover how those disabled by the Civil Wars spoke about themselves and how the petitions can tell us about life as a disabled person in the seventeenth century…

When Christopher Mowson’s petition in 1665 declared that ‘I am disabled’, it had a very different meaning to how we might understand its today. In declaring himself disabled, Mowson’s petition was commenting on the impact of his wound, his financial situation, the rights of ex-soldiers and early modern perspectives on disability. This blog approaches the petitions through the lens of disability history, exploring the lives of disabled petitioners and presenting them as individuals searching for agency.

Disability Theory

Much has been said about the medical history of the Civil Wars. Large scale conflict brings injury, medical developments and, naturally, curious historians willing to study it. As a result, the history of medicine in the Civil Wars is a subject brimming with historiography and debate. The field of disability history is, when compared to the history of medicine, a relatively new discipline. It was conceived in the 1980s with the advent of the disability rights movement and has developed alongside wider disability theory.

While the two disciplines would seem, at first glance, to be largely identical, the difference between medical history and disability history is in their approach to impairment. Medical history often sees the end goal of a disabled individual as being ‘fixed’, or in other words, being as similar to non-disabled people as possible and in doing so solely conceptualises the individual in a medical world. Disability history, on the other hand, places the disabled individual within the context of everyday life, characterising the way society is composed as being the barrier, not the individual’s disability itself. This way of conceptualising disability is called the ‘social model’ and sees exclusion occur through social, economic and political means rather than a person’s disability itself.

The main periodisation of disability historiography tends to be concerned with the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This is largely because revolutionary medical treatments and changing attitudes towards impairment transformed how disabled people were perceived. Unfortunately, this leaves the stories of pre-modern disabled people largely untold and one area that remains particularly neglected by disability historians, beyond the work of a few historians such as Geoffrey Hudson, is the Civil Wars.

The Civil War Petitions Project offers a major opportunity to expand the scope of disability history and to see the impact that Civil War wounds had on a person’s life. The petitions often describe how an individual’s disability is life limiting and gives a glimpse into how disabled people made accommodations to their routines to make them more accessible. Petitions also give a tantalising insight into how petitioners conceptualised their disability. While the vast majority of petitions were not written by the claimant themselves, their stories and their language still shine through in the scribes’ work. In that sense, the petitions come incredibly close to seeing how individuals perceived their own disabilities and how it specifically affected their lives.

Being a Disabled Petitioner in Practice

Before looking at how people described themselves, it is first important to assess how the legislation that enabled disabled petitioners affected how they presented themselves to the County court. The core piece of legislation that governed how the relief of the poor was delivered throughout the Old Poor Laws (1601-1834) was the 1601 Acte for the Reliefe of the Poore. This act placed the burden for most poor relief at a parochial level, creating Overseers for the Poor whose role was to distribute relief received from the Poor Rate tax to the most needy. The act specifically states that money should be used to relieve the ‘the lame ympotente olde blynde and such other amonge them beinge poore and not able to worke’, therefore designating the disabled and chronically ill as particularly deserving. This was developed by the 1601 Act for the Necessary Relief of Soldiers and Mariners which acted as a predecessor to Civil War era legislation about relief for the disabled. This legislation states that disabled service men were able to apply to their parish for a pension distributed at the county Quarter Sessions.

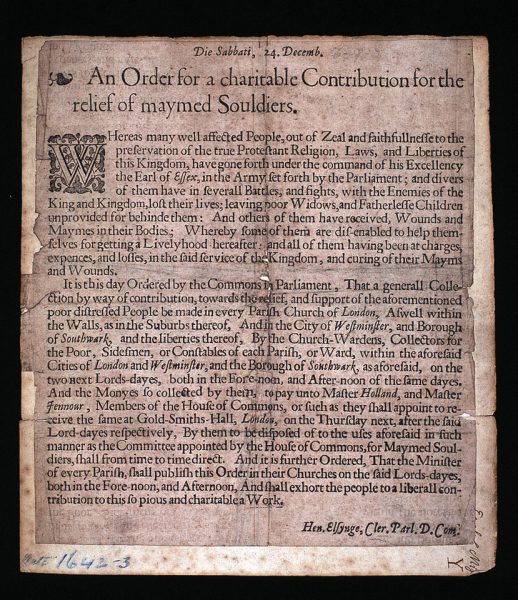

An Order for a charitable Contribution for the relief of maymed Souldiers, 1643 (image from the National Army Museum: https://collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=1967-10-82-1).

The Old Poor Law was further developed during the Civil War to accommodate for the growing number of widows, orphans and disabled veterans. Three key pieces of legislation were passed: the 1643 Ordinance for the relief and maintenance of sick and maimed soldiers, and of poor widows and children of soldiers slain in the service of the parliament, the 1647 Ordinance for relief of maimed soldiers and mariners, and the widows and orphans of such as have died in the service of the parliament during these late wars and the 1662 Act for the relief of poor and maimed officers and soldiers who have faithfully served his majesty and his royal father in the late wars. What is particularly intruiging about these acts is their use of the word ‘disabled’. The term ‘disabled’ was not used the way we use it today until the twentieth-century when language used to describe bodily difference changed. In this instance, ‘disabled’ was used to mean ‘disabled to relieve themselves by their usual labour’ or in simpler terms, unable to work due to their disability.

On a winter’s day in January 1659, Gowther Butterworth approached the Manchester Quarter Sessions asked for ‘Relief & susten[a]nce in some good measure’. In this petition he described that during his service, he contracted diseases that prevented him from working for a living. Butterworth was being described as being ‘disenabled’ to work, using the exact language from the legislation in the plea. He furthers this by saying during the wars he ‘travelled to London for Reliefe as to a sick souldier (so as aforesaid disenabled)’; however, the treatment was unsuccessful and as a result he grew ‘more sick & weake’. This petition uses the term ‘disabled’, or in this case ‘disenabled’ in the typical way described above – as being impaired to the degree that he could not work to support himself or his six children.

Other examples use the language of disablement; however, they use the more familiar term of ‘disabled’. Richard Mason’s petition at the Quarter Sessions of Derbyshire, around ten years earlier states that ‘something disabled [him] from Followinge his p[ar]ticuler Callinge’ because of his ‘Skull beinge Fractured & hee dayly growing worse & worse’. Much like the last example, Mason’s injury prevented him from pursuing his trade and having gainful employment to provide for his family. As a result he petitioned the Derbyshire Quarter Sessions using the language of the legislation to prove his eligibility.

Mobility

Beyond language, these petitions can tell us much more about life as a disabled person in the seventeenth century. These petitions give a greater insight into the lived experience of disability in the shadow of the Civil Wars. Mobility, or lack thereof, is intrinsically associated to disability; therefore, it is only natural that this theme comes out in the pleas of disabled petitioners.

Adam Crompton’s petition from 1660 uses the language of disablement discussed earlier, stating that having been ‘ridden ouer’ by horses was ‘thereby disinabled to worke for his liuing’. However, what is particularly interesting about this petition is how it describes Crompton’s lack of mobility. He is described as ‘not being able to moue or goe’ and that he was ‘lyinge vpon his bed not able to helpe himselfe’. While the petition provides no detail about the nature of Crompton’s injuries, we can assume that he must have been severely injured to be confined to his bed. While mobility aids were in their infancy, early modern disabled people did find ways to aid their mobility. These included walking sticks, crutches, wooden legs, the help of other people (as is the case in Raphe Cooper in 1650) and even using horses. This was the case in the petition of Francis Calverley and eight other other maimed soldiers which told of a veteran who had ‘lost both his feete had a litle horse which dying & failing him he is great trouble to ye rest & in great paine to trauill’. Therefore, for Crompton to have had such a diminished quality of life implies that his injury was extremely severe and maybe implies some remaining chronic pain.

Jacques Callot, Beggar Woman with Crutches. France, 17th Century (Image from The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, reproduced under a Creative Commons Zero licence).

Possibly the most common mobility aid was the use of crutches. Roger Dawson’s petition of 1653 describes that under the command of Captain Richards in Ireland, he was so ‘meamed and Lamed’ that he was unable to move ‘w[i]thout the assistance of Crutches’. As a result, he was unable to earn a living and was granted a twenty shilling gratuity and twenty shilling pension to maintain himself. Similarly, George Yearsley also used crutches as a result of his injury in Dorset under the command of Sir Thomas Aston. Yearsley underwent surgery for half a year to try to improve his condition and ‘did vndergoe much payne and sorrow’, unfortunately without result. It was only after this that George Yearsley began to use crutches. While crutches were popular, this popularity was down to their low price and availability rather than their comfort and ease of use. The ‘T-Shaped’ crutch was the mainstay of crutches for many centuries and while they did aid mobility, they limited the user’s ability to use their hands. Also, as the crutches were made of wood they lacked any cushioning leading to discomfort. Despite the flaws of early modern crutches, they provided a vital lifeline to disabled veterans to enable their mobility and facilitate their return to the wider community.

The seal of the Committee for Maimed Soldiers, used as the Civil War Petitions logo, depicts a contemporary image of a soldier with a wooden leg

It would be remiss to not mention other key examples of mobility aids during this period. Although not mentioned in the petitions, likely because of their exorbitant cost reserving them for only the gentry who would not need to petition, Sir Arthur Aston’s wooden leg and Sir Thomas Fairfax’s wheelchair are prime examples of mobility aids in this period. Aston’s leg broke in September 1644 as a result of a riding accident. His leg had to later be amputated in the December of that year after gangrene set in. This provided Aston with renewed mobility and was remarkably back serving the royalist army in Ireland as early as 1645. However, the reason Aston’s wooden leg is so famous is unfortunately much more harrowing. On the 24th August 1649, Aston, now in the position of Governor, was defending Drogheda from Cromwell’s superior besieging forces. Aston’s forces were defeated on the 10th September and he was beaten to death with his own wooden leg as the besiegers believed it contained gold pieces. While Aston’s story ends in disaster, he is a crucial example of how mobility aids enabled Civil War veterans to resume their service and how an individual’s disability did not always mean they were completely debilitated.

Sir Thomas Fairfax, on the other hand, died long after the end of the Civil Wars in 1671. In his older years, Fairfax had a series of illnesses and became increasingly frail. By 1664 his mobility was incredibly impaired due to the stone and gout. In order to remain as mobile as possible, Fairfax used a wheelchair. The magnificence of this wheelchair cannot be understated. As part of the Battle-Scarred Summer School, I greatly enjoyed the opportunity to study the wheelchair in depth, appreciating its towering size and advanced mechanisms that enabled Fairfax to propel himself. It really was ahead of its time as a piece of engineering and gave the opportunity for Fairfax to vastly improve his quality of life.

The author, Liv Bennison, standing next to the exhibit of Thomas Fairfax’s wheelchair at the National Civil War Centre.

Disability and Non-Servicemen

While disabled servicemen are the most prominent disabled petitioners, they were not the only ones. As alluded to previously, widows and orphans of the Civil Wars were also entitled to relief. Those among these groups deemed particularly needy and deserving were those who also had a disability and therefore there are some exciting examples of disability that were not connected to battle injuries.

Frances Hughson petitioned as an orphan in 1665. Her father died under the service of Parliamentarian Captain Thomas Talbot at the Battle of Marston Moor. As a result Hughson was left in the care of her grandmother, Elene Clearke, who died shortly before the petition. On occasion of her grandmother’s death, Hughson would be expected to find a way to maintain herself; however, Frances Hughson was left blind as a result of having smallpox and the King’s Evil as an infant. As a result she was ‘vnable to do anything towards her livelihood’ and requested a yearly pension ‘towards her maintenance’. Hughson’s petition was successful, unfortunately we do not know to what extent.

Jane Wood, on the other hand, petitioned as a war widow in 1672. Wood’s husband, Edward Wood, served in the royalist armies, himself gaining a disabling injury that allowed him to receive a yearly pension of ten shillings. With her husband unfortunately dead, Wood’s petition describes her as ‘a poore lame woman haueinge but one hand and almost blynde’ with very little money to support herself. As a result of her petition, she received ten shillings to repair her cottage and a pension of a shilling a week.

These examples tell us much about disability culture more widely. They show that while these women’s disabilities did not come from loyalty and service, they were viewed with similar respect and compassion.

Concluding thoughts

The examples discussed in this post only scratch the surface of the potential that Civil War petitions have for disability studies. As they are separated by time from the point of initial injury and instead take a biographical approach, the petitions hold great potential for showing how the lives of wounded servicemen have had to change and adapt to life as a disabled veteran. Also, as shown with the examples of Frances Hughson and Jane Wood, Civil War petitions have the potential to give rise to discussion about disability culture more broadly and how disabled people who did not gain their disability through warfare were treated. What these petitions all have in common, is the resilience they depict their petitioners as having. While they all are in a position of poverty, these petitioners all successfully negotiate having a disability in a vastly unequal society by finding accommodations and aids to maintain agency.

Liv Bennison has completed both a BA in History and an MA in Social and Economic History at Durham University. Her master’s thesis discussed how Disability and Chronic Illness Impacted Poor Relief and Work in Durham 1660-1760. She attended the Battle-Scarred Summer School in 2022 with the hope to study Disability and the Civil Wars.

Further Reading

Catherine Kudlick, ‘Social History of Medicine and Disability History’ in Michael Rembis, Catherine Kudlick and Kim E. Nielsen (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Disability History (Oxford, 2018).

Dan Goodley, Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction (London, 2011).

Geoffrey L. Hudson, ‘Arguing Disability: Ex-Servicemen’s Own Stories in Early Modern England, 1590–1790’, in Roberta Bivins and John V. Pickstone (eds.), Medicine, Madness and Social History: Essays in Honour of Roy Porter (Basingstoke, 2007).