HIGHLY COMMENDED IN THE BRITISH RECORDS ASSOCIATION’S JANETTE HARLEY PRIZE 2020:

https://www.britishrecordsassociation.org.uk/press-release-winner-of-the-2020-janette-harley-prize-announced/

John Balshaw’s Jigge: Singing, Star-Crossed Lovers and Signing a Civil War Petition

Some years ago, Jenni Hyde found herself sitting in the British Library reading room looking at a seventeenth-century jigge. Probably best thought of as an early modern musical, jigges were small-scale theatrical entertainments in which the story was told entirely through song. Each scene was set to the tune of a ballad, the popular songs of the early modern period which required no musical training to sing. However, as she soon discovered, this particular jigge was a rather unusual one with quite a story behind it... Jigges had been particularly popular during the Elizabethan period, but the jigge that I uncovered in the British Library was a very late example of the genre given that it wasn’t written until after the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. In my critical edition of the text, I point out that this is only one of the reasons it is especially noteworthy. Another is that it is the only extant jigge which deals explicitly with political themes – the impact of the Civil Wars on small rural communities. But although I knew the name of the jigge’s author, John Balshaw, he proved to be quite elusive. He’s not up there with the great early modern playwrights like William Shakespeare and Aphra Behn. He’s not even an oft-overlooked dramatist like Mary Wroth, whom my Lancaster colleague Alison Findlay has done so much to bring back into the limelight. In fact, as far as we know, this was the only theatrical work that Balshaw wrote. We can’t even be sure that it was ever performed. We really don’t know anything for certain apart from his name and where he lived. We know that he composed the jigge in the small Lancashire village of Brindle, because he says so at the end of the manuscript. I was therefore fascinated to discover only in May 2023 that Balshaw appears on the Civil War Petitions site, supporting the 1676 petition of another Brindle resident, Thomas Hilton, for a military pension. Set in the dying days of the Interregnum, Balshaw’s jigge is a Romeo and Juliet type of story, albeit with a happy ending. The families of the star-crossed lovers are not Montague and Capulet, but Royalist and Parliamentarian, although it has to be said that the hero and heroine themselves remain loyal to King Charles II throughout. Balshaw’s character names hint at his own allegiances. The Royalists are called Trueman, while the Parliamentarians are called Causeless! This is not particularly surprising, as Brindle was a Royalist area throughout the Civil Wars. The community even had a new parliamentarian vicar imposed because their own incumbent, Edward Rigby, was away taking part in the siege of Lathom House near Ormskirk, Lancashire, attempting to defend this Royalist stronghold from Parliament’s forces. We can only speculate on how well the new pastor’s Presbyterian beliefs went down in Brindle, where many residents, like Balshaw, clung to the Roman Catholic faith. It is interesting, in fact, that in the same year that Balshaw appeared as a witness to Thomas Hilton’s infirmity, the recusant rolls show that a John Balshaw from Brindle was fined for not attending church. Nevertheless, we also know from the parish church registers that a John Balshaw was buried in Brindle in 1679. I think, although I cannot prove it, that these John Balshaws were the author of the jigge. What is fascinating for me, though, is less Balshaw’s relative obscurity as an author than the way that he brings into his jigge so many of the problems that the Civil Wars caused for local communities. Captain Causeless started life as a ploughman, but before the piece begins he has been rewarded for his service in Cromwell’s army with lands confiscated from a Royalist ‘delinquent’. Although he now has at his command ‘poor peasants, rich yeomen and gentry likewise’, he lacks the social standing (and indeed, the wealth) of the traditional landed gentry. Trueman is, or was, the affluent local Justice of the Peace, until his loyalty to the king sees him threatened with sequestration, a process of asset stripping in which the king’s supporters’ lands were confiscated by parliament. So Balshaw’s jigge reflected common concerns about the ‘world turned upside down’ of the Civil War period. The deciding factor in the happy ending to the story is the return of Charles II from exile. Contemporary pamphlets complained about how the traditional local elites were undermined by base-born opportunists, who owed their positions solely to their allegiance to parliament. In fact, so central to the plot is the royalist/parliamentarian divide that I was frankly surprised that none of the scenes were set to the tune of the famous Royalist ballad The King Enjoys His Own Again. Moreover, given that Balshaw describes himself in the jigge’s dedication as an ‘old decayed poet, new fallen in amongst the beggars’, I suspect this theme of fortune’s ups and downs and its impact on both wealth and social status was particularly resonant to both John Balshaw and his audience. Obviously, the horrors of war were real for those people who took up arms either for king or parliament, but the impact of the Civil Wars was felt much more widely. The economic effects of the wars were enormous, not only in terms of the number of men killed (which is famously higher as a percentage of the population than the casualties of the First World War), but also in terms of those men who returned to rural communities unable to work because of their injuries. Thomas Hilton’s petition to the Wigan Quarter Sessions in January 1676 would seem to bear this out. Hilton was a labourer, but his war wounds meant that he was in a ‘deplorable condition’. Having fought under the command of one of the leading Lancashire Catholics, Sir Thomas Tyldesley, in a skirmish near Chester, he had sustained a bullet wound to the chest and indeed, the bullet still remained in his breast. Moreover, his leg had been broken in several places and he had several other wounds. Among the men who supported his petition for a pension from the king were some of the key members of the Brindle community. William Gerrard was presumably descended from the Gerrards who had once held the manor of Brindle, which the family sold in 1582 to pay their fines as recusants who refused to attend the Church of England.[1] Interestingly, although the 1673 Michaelmas hearth tax returns for the parish include several Gerrards, William is not one of them.[2] Nevertheless, several of the men who endorsed Hilton’s petition appear in the lists. William Bennett, William Hilton and Thomas Hilton himself appear consecutively in the return, only a few entries down from Balshawe House. Thomas Sharrocke, another of Hilton’s supporters, also appears in the list. All five properties had a single chargeable hearth – indeed, so did the majority of properties in the village. Although Hilton’s petition appears to be signed by Thomas Bailson, I suspect that Thomas simply forgot to cross his ‘t’ – there are many Baitsons in the local area at the time! As part of the 50th anniversary celebrations for Lancaster University’s award-winning Regional Heritage Centre, I was asked to stage what we believe to be the world premiere of the jigge in Brindle on 17 June 2023. The performance begins at 7pm with a short talk to set the jigge in its historical context. The musical itself consists of a prologue, which I will perform, followed by four scenes, each of which is set to a different ballad tune which was popular at the time that Balshaw wrote his jigge. With a cast from across the university, including students from History, English Literature and Creative Writing, Computing, Sociology, and Linguistics, supported by actors and musicians from the early music ensemble Passamezzo, we hope to bring John Balshaw’s Jigge to life, and give modern audiences a sense of what this piece might have sounded like. Balshaw’s story revolves around a girl, Lucina, who has been cheated out of her inheritance by her wicked, Parliamentarian uncle, Captain Causeless. Although it is unclear from the text, it would seem that Lucina’s parents are dead, and were presumably Royalists. Her love interest, Samwell Trueman, is the son of the local Justice of the Peace. I suspect that probably this is a courtesy title rather than reflecting his actual position, as many Royalists were stripped of their roles as community officials during the Interregnum. In order to shore up the fortunes of both families, the Captain cooks up a plot to marry his daughter, Juviana, to Samwell. He sells this to the Justice as a way to prevent the confiscation of his lands. Lucina disguises herself as a serving maid in order to keep tabs on Juviana’s attempts to seduce Samwell, and the servant Bobbe introduces an element of farce to the proceedings as he laments for his previous relationship with Juviana while he reports to the Captain how well the romance is (or rather isn’t) advancing. The Justice, meanwhile, has no intention of marrying his son to one of ‘baser blood’, and is mightily relieved to hear that Bobbe might hold the key to calling off the contract. In the event, however, it is the return of the king that up-ends the proceedings, as Lucina is restored to her lands and the Causlesses are exiled for their deception. Although we are unsure whether the jigge has ever been performed in the past, we think that if it had been, the performance would have taken place in one of the local gentry homes. Our performance will take place in Brindle’s Community Hall, close to the Parish Church which has stood on that site since Balshaw’s time. Thomas Hilton’s petition to the Quarter Sessions adds another layer of local knowledge to the jigge – as I suspected all along, I now know that the residents of Brindle knew first-hand how devastating the effects of the Civil Wars could be. [1] ‘The parish of Brindle’, pp. 75-81 in William Farrer and J. Brownbill (eds.), A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 6 (London, 1911) via British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol6/pp75-81 [accessed 29 May 2020]. [2] I am grateful to Andrew Wareham of the Centre for Hearth Tax Research at Roehampton University for supplying me with the 1673 Lancashire hearth tax returns transcript ahead of its publication on Hearth Tax Digital, https://gams.uni-graz.at/context:htx [accessed 19 May 2023]. Dr Jenni Hyde is a Trustee of the Historical Association and Lecturer in Early Modern History at Lancaster University. Her first book, Singing the News: Ballads in Mid-Tudor England, was published in 2018 by Routledge while her critical edition of a seventeenth-century ‘musical’, John Balshaw’s Jigge: Revelry and Royalism in Restoration Lancashire, appeared in 2021. She is a former music teacher, a classically-trained soprano and a keen folk singer. Further Reading Stephen Bull, ‘A General Plague of Madness’: The Civil War in Lancashire (Lancaster: Carnegie Press, 2009) Roger Clegg and Lucie Skeaping, Singing Simpkin and Other Bawdy Jigs (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2014) Jenni Hyde, John Balshaw’s Jigge: Revelry and Royalism in Restoration Lancashire (Lancaster: Lancaster University Regional Heritage Centre, 2021)

Read More

‘Meamed and Lamed’: Approaching Civil War Petitions through the Lens of Disability History

We have published several blogs on what the documents on Civil War Petitions can reveal about the medical history of the Civil Wars but so far we have said little about what the petitions reveal about disability history. Therefore, in this week's blog, Liv Bennison uses the petitions to uncover how those disabled by the Civil Wars spoke about themselves and how the petitions can tell us about life as a disabled person in the seventeenth century... When Christopher Mowson's petition in 1665 declared that 'I am disabled', it had a very different meaning to how we might understand its today. In declaring himself disabled, Mowson's petition was commenting on the impact of his wound, his financial situation, the rights of ex-soldiers and early modern perspectives on disability. This blog approaches the petitions through the lens of disability history, exploring the lives of disabled petitioners and presenting them as individuals searching for agency. Disability Theory Much has been said about the medical history of the Civil Wars. Large scale conflict brings injury, medical developments and, naturally, curious historians willing to study it. As a result, the history of medicine in the Civil Wars is a subject brimming with historiography and debate. The field of disability history is, when compared to the history of medicine, a relatively new discipline. It was conceived in the 1980s with the advent of the disability rights movement and has developed alongside wider disability theory. While the two disciplines would seem, at first glance, to be largely identical, the difference between medical history and disability history is in their approach to impairment. Medical history often sees the end goal of a disabled individual as being 'fixed', or in other words, being as similar to non-disabled people as possible and in doing so solely conceptualises the individual in a medical world. Disability history, on the other hand, places the disabled individual within the context of everyday life, characterising the way society is composed as being the barrier, not the individual's disability itself. This way of conceptualising disability is called the 'social model' and sees exclusion occur through social, economic and political means rather than a person's disability itself. The main periodisation of disability historiography tends to be concerned with the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This is largely because revolutionary medical treatments and changing attitudes towards impairment transformed how disabled people were perceived. Unfortunately, this leaves the stories of pre-modern disabled people largely untold and one area that remains particularly neglected by disability historians, beyond the work of a few historians such as Geoffrey Hudson, is the Civil Wars. The Civil War Petitions Project offers a major opportunity to expand the scope of disability history and to see the impact that Civil War wounds had on a person's life. The petitions often describe how an individual's disability is life limiting and gives a glimpse into how disabled people made accommodations to their routines to make them more accessible. Petitions also give a tantalising insight into how petitioners conceptualised their disability. While the vast majority of petitions were not written by the claimant themselves, their stories and their language still shine through in the scribes' work. In that sense, the petitions come incredibly close to seeing how individuals perceived their own disabilities and how it specifically affected their lives. Being a Disabled Petitioner in Practice Before looking at how people described themselves, it is first important to assess how the legislation that enabled disabled petitioners affected how they presented themselves to the County court. The core piece of legislation that governed how the relief of the poor was delivered throughout the Old Poor Laws (1601-1834) was the 1601 Acte for the Reliefe of the Poore. This act placed the burden for most poor relief at a parochial level, creating Overseers for the Poor whose role was to distribute relief received from the Poor Rate tax to the most needy. The act specifically states that money should be used to relieve the 'the lame ympotente olde blynde and such other amonge them beinge poore and not able to worke', therefore designating the disabled and chronically ill as particularly deserving. This was developed by the 1601 Act for the Necessary Relief of Soldiers and Mariners which acted as a predecessor to Civil War era legislation about relief for the disabled. This legislation states that disabled service men were able to apply to their parish for a pension distributed at the county Quarter Sessions. The Old Poor Law was further developed during the Civil War to accommodate for the growing number of widows, orphans and disabled veterans. Three key pieces of legislation were passed: the 1643 Ordinance for the relief and maintenance of sick and maimed soldiers, and of poor widows and children of soldiers slain in the service of the parliament, the 1647 Ordinance for relief of maimed soldiers and mariners, and the widows and orphans of such as have died in the service of the parliament during these late wars and the 1662 Act for the relief of poor and maimed officers and soldiers who have faithfully served his majesty and his royal father in the late wars. What is particularly intruiging about these acts is their use of the word 'disabled'. The term 'disabled' was not used the way we use it today until the twentieth-century when language used to describe bodily difference changed. In this instance, 'disabled' was used to mean 'disabled to relieve themselves by their usual labour' or in simpler terms, unable to work due to their disability. On a winter's day in January 1659, Gowther Butterworth approached the Manchester Quarter Sessions asked for 'Relief & susten[a]nce in some good measure'. In this petition he described that during his service, he contracted diseases that prevented him from working for a living. Butterworth was being described as being 'disenabled' to work, using the exact language from the legislation in the plea. He furthers this by saying during the wars he 'travelled to London for Reliefe as to a sick souldier (so as aforesaid disenabled)'; however, the treatment was unsuccessful and as a result he grew 'more sick & weake'. This petition uses the term 'disabled', or in this case 'disenabled' in the typical way described above - as being impaired to the degree that he could not work to support himself or his six children. Other examples use the language of disablement; however, they use the more familiar term of 'disabled'. Richard Mason's petition at the Quarter Sessions of Derbyshire, around ten years earlier states that 'something disabled [him] from Followinge his p[ar]ticuler Callinge' because of his 'Skull beinge Fractured & hee dayly growing worse & worse'. Much like the last example, Mason's injury prevented him from pursuing his trade and having gainful employment to provide for his family. As a result he petitioned the Derbyshire Quarter Sessions using the language of the legislation to prove his eligibility. Mobility Beyond language, these petitions can tell us much more about life as a disabled person in the seventeenth century. These petitions give a greater insight into the lived experience of disability in the shadow of the Civil Wars. Mobility, or lack thereof, is intrinsically associated to disability; therefore, it is only natural that this theme comes out in the pleas of disabled petitioners. Adam Crompton's petition from 1660 uses the language of disablement discussed earlier, stating that having been 'ridden ouer' by horses was 'thereby disinabled to worke for his liuing'. However, what is particularly interesting about this petition is how it describes Crompton's lack of mobility. He is described as 'not being able to moue or goe' and that he was 'lyinge vpon his bed not able to helpe himselfe'. While the petition provides no detail about the nature of Crompton's injuries, we can assume that he must have been severely injured to be confined to his bed. While mobility aids were in their infancy, early modern disabled people did find ways to aid their mobility. These included walking sticks, crutches, wooden legs, the help of other people (as is the case in Raphe Cooper in 1650) and even using horses. This was the case in the petition of Francis Calverley and eight other other maimed soldiers which told of a veteran who had 'lost both his feete had a litle horse which dying & failing him he is great trouble to ye rest & in great paine to trauill'. Therefore, for Crompton to have had such a diminished quality of life implies that his injury was extremely severe and maybe implies some remaining chronic pain. Possibly the most common mobility aid was the use of crutches. Roger Dawson's petition of 1653 describes that under the command of Captain Richards in Ireland, he was so 'meamed and Lamed' that he was unable to move 'w[i]thout the assistance of Crutches'. As a result, he was unable to earn a living and was granted a twenty shilling gratuity and twenty shilling pension to maintain himself. Similarly, George Yearsley also used crutches as a result of his injury in Dorset under the command of Sir Thomas Aston. Yearsley underwent surgery for half a year to try to improve his condition and 'did vndergoe much payne and sorrow', unfortunately without result. It was only after this that George Yearsley began to use crutches. While crutches were popular, this popularity was down to their low price and availability rather than their comfort and ease of use. The 'T-Shaped' crutch was the mainstay of crutches for many centuries and while they did aid mobility, they limited the user's ability to use their hands. Also, as the crutches were made of wood they lacked any cushioning leading to discomfort. Despite the flaws of early modern crutches, they provided a vital lifeline to disabled veterans to enable their mobility and facilitate their return to the wider community. It would be remiss to not mention other key examples of mobility aids during this period. Although not mentioned in the petitions, likely because of their exorbitant cost reserving them for only the gentry who would not need to petition, Sir Arthur Aston's wooden leg and Sir Thomas Fairfax's wheelchair are prime examples of mobility aids in this period. Aston's leg broke in September 1644 as a result of a riding accident. His leg had to later be amputated in the December of that year after gangrene set in. This provided Aston with renewed mobility and was remarkably back serving the royalist army in Ireland as early as 1645. However, the reason Aston's wooden leg is so famous is unfortunately much more harrowing. On the 24th August 1649, Aston, now in the position of Governor, was defending Drogheda from Cromwell's superior besieging forces. Aston's forces were defeated on the 10th September and he was beaten to death with his own wooden leg as the besiegers believed it contained gold pieces. While Aston's story ends in disaster, he is a crucial example of how mobility aids enabled Civil War veterans to resume their service and how an individual's disability did not always mean they were completely debilitated. Sir Thomas Fairfax, on the other hand, died long after the end of the Civil Wars in 1671. In his older years, Fairfax had a series of illnesses and became increasingly frail. By 1664 his mobility was incredibly impaired due to the stone and gout. In order to remain as mobile as possible, Fairfax used a wheelchair. The magnificence of this wheelchair cannot be understated. As part of the Battle-Scarred Summer School, I greatly enjoyed the opportunity to study the wheelchair in depth, appreciating its towering size and advanced mechanisms that enabled Fairfax to propel himself. It really was ahead of its time as a piece of engineering and gave the opportunity for Fairfax to vastly improve his quality of life. Disability and Non-Servicemen While disabled servicemen are the most prominent disabled petitioners, they were not the only ones. As alluded to previously, widows and orphans of the Civil Wars were also entitled to relief. Those among these groups deemed particularly needy and deserving were those who also had a disability and therefore there are some exciting examples of disability that were not connected to battle injuries. Frances Hughson petitioned as an orphan in 1665. Her father died under the service of Parliamentarian Captain Thomas Talbot at the Battle of Marston Moor. As a result Hughson was left in the care of her grandmother, Elene Clearke, who died shortly before the petition. On occasion of her grandmother's death, Hughson would be expected to find a way to maintain herself; however, Frances Hughson was left blind as a result of having smallpox and the King's Evil as an infant. As a result she was 'vnable to do anything towards her livelihood' and requested a yearly pension 'towards her maintenance'. Hughson's petition was successful, unfortunately we do not know to what extent. Jane Wood, on the other hand, petitioned as a war widow in 1672. Wood's husband, Edward Wood, served in the royalist armies, himself gaining a disabling injury that allowed him to receive a yearly pension of ten shillings. With her husband unfortunately dead, Wood's petition describes her as 'a poore lame woman haueinge but one hand and almost blynde' with very little money to support herself. As a result of her petition, she received ten shillings to repair her cottage and a pension of a shilling a week. These examples tell us much about disability culture more widely. They show that while these women's disabilities did not come from loyalty and service, they were viewed with similar respect and compassion. Concluding thoughts The examples discussed in this post only scratch the surface of the potential that Civil War petitions have for disability studies. As they are separated by time from the point of initial injury and instead take a biographical approach, the petitions hold great potential for showing how the lives of wounded servicemen have had to change and adapt to life as a disabled veteran. Also, as shown with the examples of Frances Hughson and Jane Wood, Civil War petitions have the potential to give rise to discussion about disability culture more broadly and how disabled people who did not gain their disability through warfare were treated. What these petitions all have in common, is the resilience they depict their petitioners as having. While they all are in a position of poverty, these petitioners all successfully negotiate having a disability in a vastly unequal society by finding accommodations and aids to maintain agency. Liv Bennison has completed both a BA in History and an MA in Social and Economic History at Durham University. Her master's thesis discussed how Disability and Chronic Illness Impacted Poor Relief and Work in Durham 1660-1760. She attended the Battle-Scarred Summer School in 2022 with the hope to study Disability and the Civil Wars. Further Reading Catherine Kudlick, 'Social History of Medicine and Disability History' in Michael Rembis, Catherine Kudlick and Kim E. Nielsen (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Disability History (Oxford, 2018). Dan Goodley, Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction (London, 2011). Geoffrey L. Hudson, ‘Arguing Disability: Ex-Servicemen’s Own Stories in Early Modern England, 1590–1790’, in Roberta Bivins and John V. Pickstone (eds.), Medicine, Madness and Social History: Essays in Honour of Roy Porter (Basingstoke, 2007).

Read More

‘Lost and impoverished for ever’: The effect of the Civil Wars on Local Communities as seen through Civil War Petitions

As part of the 'Battle-Scarred' Summer School held at Merton College in July 2022, the Civil War Petitions team issued a challenge to the students on the course to write a blog post which reflected upon the petitions. One student who accepted that challenge was Sarah Cooley and we are delighted to publish her blog this week. Continuing the themes raised in the last blog by Maureen Harris, Sarah examines the effects of the Civil Wars on civilian communities at a local level... Petitioning for compensation during and after the British civil wars was not just the preserve of those, or the family of those, who fought in the field engagements like Edgehill or Naseby, or people who served as engineers, surgeons, and drivers (see David Appleby’s blog – ‘They also served’); Petitions also came from civilians who were impacted when the conflict crashed into their communities: People like William Summer of Leicester whose house and orchard were destroyed ‘before ye taking of the towne, for ye better securing thereof’ and then whose goods were plundered when the town was sacked. His livelihood and property were destroyed, and his family were traumatised. This blog explores what the petitions can tell us about local communities during the civil wars. They shed light on some of the reasons why men joined the army, the attitudes of local officials to the conflict, and the financial losses families incurred. Allegiances Due to the wording of the legislation that governed who was eligible for compensation, explicit professions of loyalty particularly to the Royalist cause are very noticeable. For example, Mary Ewin of Melling Lancashire who petitioned after her husband abandoned their family, professed that they had been ‘true and loyall subiects to his Ma[jes]tie and for their loyaltie and faith theirin were brought into povertie in these late and vnhappy distractions…’. However, a theme that runs through the petitions is that men, like Thomas Stockton (Aliis Stockon) and Thomas Fisher, enlisted through necessity. - ‘pouertie enforcing’ the former and the latter having no option but ‘through extreame hung[e]r… to leaue her w[i]the 2 poore smale children and betake him to a sould[ie]rs life…’. Both would likely have done so in the hope of regular pay as well as a pension for their wives and children should they be killed in service. Furthermore, emphasising their poverty supported their argument that they were worthy of help while signalling that they had been let down by the very system designed to support them. Authority While some chose military service as an alternative to destitution, others had it thrust upon them due to the practice of local conscription - a recruitment tool used by both sides during the wars and implemented by the parish constables. Some like Richard Dobson were caught up in the process; his wife Jane petitioned for relief because he had been ‘by Accident was in the Towne of Aughton about his affaires…’ and ‘was by the Constable & officers of the said Towne of Aughton pressed for a Souldier & soe taken to the sea…’ Jane presented Richard as having been in the wrong place at the wrong time. There were also those whose conscription appeared to be more targeted as the cases of Edmund Rowse of Methwold, Norfolk, and John Tomptson of Tunstall, Lancashire suggest. It is not known why these men were chosen, however, Rowse had been recently acquitted of horse stealing and Tomptson was a traveling rope maker so pressing them into military service it can be argued helped fill the local constables’ quotas and removed two potential troublemakers from the community. Local officials were also responsible for bringing petitions either on behalf of or against their parishioners. The churchwardens of Tunstall petitioned against John Tomptson’s wife mentioned above ‘because She and hir Childeren is now able to maintaine themselfes and She for hir part is grone to be a very drunken Realinge woman.’ Their counterparts in Bolton however, petitioned on behalf of Marie Houlte whose son had been killed so that ‘shee maie bee releeued amongst the rest of the widdowes and haue allowance towards her Liuelyhood nowe haueinge noe other Meanes to subsist withall.’ Not that this was an altruistic act; for a financial settlement from the county committee removed the person concerned from reliance on the parish poor rate. Agency and advocacy The petitioning process also illuminated community and family disagreements and the petitions of Jenet Pearson highlight the familial split of allegiances which sometimes occurred. She applied for assistance because her husband, was imprisoned by Parliamentarian forces and she had been evicted by her Royalist sympathising stepson from ‘the said Tenemente which should haue Maintained me and fiue small Children but also all my goodes till it came to my beds where my said Children did lye on & conerted [sic.] them to his owne vse…’. Pearson’s petitions, the first dated 1650 with a subsequent one submitted in 1653, illustrate the agency and persistence of petitioners in achieving their aims. The first-person language and non-standard formulae of the earlier appeal indicate that this was Pearson’s ‘voice’ though possibly through dictation to a literate friend. However, by her second petition of 1653, Jenet had come to realise that she was entitled to financial help from the army and had been ‘deprived thereof by some indirect meanes of the paymaster’ and that due to her children’s poor health she was entitled to an uplift in her financial assistance ‘to receaue such allowance as is granted to others of the like condic[i]on…’ This implies that she had taken professional advice, a theory corroborated by the third person language and standard formula of the petition. The role of local community networks and the advocacy of neighbours is also apparent in the petitions through the role of the endorsers, those who countersigned petitions. In some instances, such as the petition in 1657 of Jane Cooke of Garthiffe, Cheshire, and who requested to remain as a pensioner, the endorsers supported the claim. However, the motivations of the supporters are more difficult to determine. Did it come from family and friends who wished to see the petitioner gain all the help to which they were entitled or was it from parish officials mindful of the potential extra burden on the parish poor rate should no pension be given. In other cases, for example that of Nathaniel Maund of Tenbury, Worcestershire, support from the community was not forthcoming. Maund had been granted assistance of 1s 4d a week, which the county justices had ordered his parish to provide, but in 1680 he was the subject of a counterclaim by the ‘Minister & Church-wardens, with severall others ye Inhabitants of ye said Town’, who argued that Maund was not deserving of the money as he used it to buy drink and was ‘a common drunkard; a Railer, & will abuse any of ye Town or parish with most base & opprobrious language.’ Abuses Like the petition of William Summer above, some of the documents record the abuses suffered by civilians when military activities landed on their doorsteps. The work done by Dr Maureen Harris and her team on the Warwickshire Loss Accounts identifies a large number of potential claimants of material losses as a result of Parliamentarian activity from 1642-1646 but this is not reflected within the petitioning process of the county pensions scheme. The petitions which do survive show the direct impacts the fighting had on communities. For some, like Margaret Pratchet of Nantwich, recompense for these impacts was the reason for petitioning. In 1655 she was still owed arrears of £22 9s 6d for quartering maimed soldiers. For others, the loss of personalty was referenced in their petitions to add weight to a claim for support. Matthew Bakewell of Uttoxeter ‘was spoiled of all that he had’ when Queen Henrietta Maria’s army under Colonel Tyldesley captured and plundered the town of Burton in 1643. This loss of goods, however, was not the reason for his petition; old age and ill health curtailed his ability to earn a living to support his orphaned grandchildren. Abuse in the form of physical assault was also recorded by Anne Boyde, widow of Lieutenant William Boyde of the Gloucester garrison as she stated she was stripped naked and robbed by her royalist captors. Anne’s accusation raises wider questions about the treatment of prisoners and at the time would also have fed into the Parliamentarian narratives around the behaviour of the English Royalists by comparing their actions to those with which the Irish were accused against Protestant settlers in 1641. The above examples demonstrate how the civil war petitions can be used to explore the relationships within communities and between communities and local authorities. They can be used to identify why people took up arms and how the local administration could potentially use conscription to their advantage. In addition, they also help with understanding how non-combatants were affected on a physical and emotional level and the extent to which individuals had the agency to seek redress. Furthermore, the petitions illustrate the community networks and the economy of makeshifts which people used to help them “get by” and how the support or lack of support from the same community, together with the narrative of the deserving or undeserving poor could enhance or diminish a petitioner’s case. Sarah Cooley worked as an archivist and then in volunteer management for many years, before returning to study in 2019 to read for an MA History (Local History) at the University of Leicester. In 2022, she commenced study for a DPhil in English Local History through the Department of Continuing Education at the University of Oxford. Her research interests concern the relationships between the British Civil War garrisons in Warwickshire and Staffordshire, and their local communities.

Read More

Civilian Suffering in the Civil War: the case of Tysoe in Warwickshire

In a previous blog, David Appleby described how the Civil War Petitions team often agonized over which claimants to military welfare to exclude from the project, many of those not making the cut being maimed civilians. Here, Dr Maureen Harris looks at a series of Civil War documents, the 'Loss Accounts', which focus specifically on civilians and the suffering caused by their financial and material losses in the First English Civil War (1642-6). As a result of a unique project, volunteers have for the first time transcribed and tabulated all the known 'Loss Accounts' for a single county: Warwickshire. The initiative was sponsored by the Dugdale Society with the Friends of the Warwickshire County Record Office and financially supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. Warwickshire has probably the best run of 'Loss Accounts' for the whole of England and Wales (some counties have few or none) and most of the original documents are at The National Archives (TNA) in the series SP 28. The Tysoe 'Account' discussed here (TNA: SP 28/184/4 and /2) is one of nearly 200 for Warwickshire now available on a publicly-accessible database hosted by Warwickshire County Record Office (WCRO) at: https://heritage.warwickshire.gov.uk/civilwaraccounts. 'Your Petitioner being a poore man and aged….' The petition of Thomas Tasker, a labourer of Epwell in Oxfordshire, is not, as might be expected, a plea for financial aid for a maimed soldier in the 'Civil Wars Petitions' project. Rather surprisingly it is one of two petitions which form part of the 'Loss Account' for Tysoe in Warwickshire, a document that evaluates the financial and material losses suffered by local inhabitants through parliamentary activity in their constablery. The two petitions follow the usual pattern of those in the 'Civil Wars Petitions' project with an address to the County Committee for Accounts and details of the petitioner's experience couched in the usual obsequious language and with prayers offered for County Committee members. Tasker's is signed but neither have the customary signatures of supporters. This blog looks at what the two petitions tell us about civilian suffering in the First Civil War in Warwickshire and why they might have been included in the Tysoe 'Account'. As Ann Hughes has shown, the parliamentary Committee of Accounts ordered the compilation of 'Loss Accounts' for constableries (usually the same as parishes) throughout the kingdom after the defeat of Charles I and his royalist forces at the battle of Naseby. Their compilation resulted from 'bitter intra-parliamentarian divisions' between moderates wanting a peaceful settlement with the King and fearful of 'military domination and autocratic committees' as opposed to the 'energetic war regime'. The 'Accounts' were to cover the period from the start of the 'Long Parliament' in late 1640 until the end of 1646. They are sometimes called 'compensation' accounts although there is no evidence that compensation was ever paid in any systematic way. Compilers, usually constables and 'chief inhabitants', were to include all losses of money, plate, horses, arms, household goods, rents, provisions, free quarter (free board and lodging for passing soldiers) and payments of taxes of all sorts. They were also to include the names of the parliamentary officers, soldiers or officials who had received, taken or seized these items. Losses from royalist activity should not have been included but quite often were. The inclusion of formal petitions for redress in Warwickshire 'Loss Accounts' is rare but Tasker's petition and that of Elizabeth Clarke are part of the 'Account' for the constablery of Tysoe in south Warwickshire (TNA: SP 28/184/2). Epwell was in the neighbouring parish of Swalcliffe, just over the Oxfordshire border, and Tasker's request for payment for the loss of goods and livelihood, along with a complaint of another Epwell man, Walter Medowes, may have been included in the Warwickshire returns by accident, or because both complaints relate to harsh treatment by the commander of a nearby Warwickshire garrison. He was Major George Purefoy, the young governor of the small Compton House garrison in the parish of Compton Wynyates adjacent to Tysoe. Compton had been the ancestral home of the royalist Earls of Northampton but was seized by the parliamentarians in June 1644 and the Tysoe 'Account' reveals the extent to which a governor like Purefoy could terrorize the local population. A succession of Tysoe petty constables had the unenviable task of acting on his forty or more warrants. One was addressed to the 'most base Malignant Counstable and Townes of Tysoes [sic]', commanding the constable to send a labourer from each household for a week's compulsory work 'upon paine of imprisonment and plunderinge'. Shortly after, Purefoy ominously commanded the constable and chief inhabitants 'to Answere to such thinges as should be laide to their charge'. Four days later he ordered the constable 'upon paine of Death' to send forty labourers, four cart-teams and all the available provision to the Compton garrison. Similar 'blustering Warrants' (as Mercurius Aulicus put it) confidently signed by Purefoy, were sent to constables in north Oxfordshire also controlled by troops from Compton and Warwick Castle garrisons. The Tysoe 'Loss Account' includes not only the petitions and detailed claims for recompense from individuals but also lists of named inhabitants, men and women, forced to undertake labouring tasks for long periods without pay: digging, pulling down walls, hay-making, breaking ice (presumably a defensive precaution to prevent a royalist attack across the moat in winter) and using horse-teams to carry turf, wood and muck. As David Appleby has pointed out waggoners and their carts were often conscripted from the local population and could suffer the same dangers of injury and death as soldiers. Nicholas Tysoe, constable of Tysoe in 1645, was sent to carry provisions and provender to the guard at nearby Ratley. He also paid for two carts, both lost when they were taken for Sir William Waller's use. William Callowe sent his team, cart and 'a man' to serve at Compton garrison for thirty days at a cost to him of six pounds. In another 'Loss Account', for Tanworth-in-Arden Heathside (TNA: SP 28/182/1 f5v), Thomas Disson, a carrier between Tanworth and London, was pressed into service with his wagon for six weeks to carry ammunition from London to Oxfordshire. Even though the better-off Tysoe residents could afford to hire labourers to perform work or fetch and carry for them, Major Purefoy's demands meant money and time were diverted away from the normal economic activities of farming, craft production and selling goods and produce. Purefoy's autocratic governance fell particularly heavily on Thomas Tasker and Walter Medowes. They had, they said, been 'wrongfully' and 'unjustly' imprisoned. Medowes' brief account tells of lost clothes, food and household goods but also of being hanged 'by neck and ristes' during his three weeks' imprisonment at Compton House. Tasker's petition speaks of goods being 'violently' taken away in the middle of a December night from him and his wife, both 'aged'. The Major's 'harsh speeches', unjust treatment and the 'sudden fright' of the attack rendered the couple 'sickly and weake' and unable to work and suggests trauma from a form of psychological torture. Arbitrary imprisonment, as experienced by Tasker and Medowes, seems to have been used by Purefoy to subdue the Tysoe inhabitants. Henry Eglington was incarcerated at Compton House, as was William Callowe who was not released until he had provided Purefoy with eight hundredweight of butter and seven hundredweight of cheese. Two Tysoe residents, Robert Rose and William Bratford, who had been former soldiers 'in the King's army' and had returned home to 'make [their] peace', were not surprisingly imprisoned by Purefoy until they were ransomed. Raphe Wilcox's and Henry Middleton's sons, and Rose Mister's servant, were seized on their way to the markets at Warwick and Stratford and were taken to Warwick Castle. The governor there, Colonel John Bridges, would not release them, or the goods they were carrying, until a substantial ransom was paid. The opportunity to collect ransom-money, to raise income for military expenses, was probably the chief reason for these men being seized but they may also have been suspected of carrying messages or spying. Anne Malins' husband and John Mister were both imprisoned for ransom at Warwick while trying to retrieve horses seized by parliament troops. Mister valued his horse at £8, the price for a superior animal, though this was nothing compared with Thomas Clerke of Wolfhamcote's valuation of £30 for the seizure of his 'great Bay horse fower yeres old' (TNA: SP 28/184/6 f3v). The average value for a horse was £4 to £6, or £2 to £3 for an inferior one. Tysoe man, Edward Boreman, had his good horse taken in exchange for a poor one and claimed a loss of £4. Some stolen animals were found and redeemed for perhaps half the animal's full value, but many horses died in battles and skirmishes or, if horses were returned or retrieved, they had often been worked so hard that they suffered illness or death. Most of Tysoe's 114 horses, mares, geldings and colts reportedly taken by parliament soldiers probably died. The seizure of horses (and sometimes oxen) resulted in the inability of farming communities to function. A Rowington man complained of 'hyndrance of Tillage' when all his cattle were taken including, presumably, his plough-team (TNA: SP 28/185 f60v), while the inhabitants of Lillington excused themselves to the Earl of Denbigh, Warwickshire's parliamentarian commander, who had demanded yet more horses for military use. They were, they said, 'wonderfully willing' to comply but heavy quartering, loss of seed-corn taken to feed cavalry horses, and particularly the 'spoyling some of our horses, & exchanging others' meant they were unable to accede to his request (WCRO: CR 2017/10/67). A second rare 'humble' petition in the Tysoe 'Account' is from the widowed Elizabeth Clarke and highlights a common complaint in many 'Accounts'; the burden of providing free food, drink and lodging for passing troops, sometimes in large numbers, and the 'unjust' plunder of essential items or prized possessions. Heavy quartering is described in the 'Loss Account' for Burmington, a small village near Tysoe with only 28 households. In June 1644, 450 of Waller's London foot-soldiers were quartered there for two days (TNA: SP 28/182/3). Stockton, a small township of 42 households in east Warwickshire, endured even heavier quartering with ten incidents between 1644 and 1647, often of hundreds of cavalry at a time such as Colonel Hammon's 800 horse-troops quartered there for two days and nights in July 1644 (TNA: SP 28/183/11). Cavalry horses were frequently left to graze unchecked, eating corn and pulses in the fields, meadow-grass reserved for hay-making or simply trampling growing crops. Mistress Clapham at Willenhall complained that Colonel Vermuyden's 2000 horses had 'Eaten up all my grasse, and spoyled my Corne and his men had all my provision in the house to the vallew of £30' (TNA: SP 28/182/2 f3v). Widow Clarke's Tysoe petition seeks redress for frequent and unauthorized quartering by Major Purefoy's troops and the plundering of a bed and hangings 'unjustly taken from her' by three of his soldiers. Her case was not particularly unusual. In the Tysoe 'Account' the bill of losses immediately before her petition is from Isabell Meakins, a widow of Tysoe Lodge, who claimed £12 10s for provisioning 500 men and horses of Waller's and some of his ox-teams in June 1643, stating she had lost some of her tax receipts when her house was plundered. Francis Clarke, a Tysoe gentleman, claimed £300 for loss of horses and most of his household goods and possessions as well as suffering heavy losses in tax, quartering and money. In large garrison towns such as Coventry and Warwick, and in villages near smaller garrisons, troops were quartered on a semi-permanent basis, usually in ordinary civilian homes where their armed presence must have been disturbing, particularly when they were 'strangers' from outside the locality. As David Appleby has found, the Scots Covenanter army, which swept through Warwickshire in the summer of 1645, was starved of money and food and plundered ruthlessly. It became deeply unpopular, and many 'Accounts' have a separate section for 'Losses from the Scots'. Even local troops regularly raided homes, smashed windows, stole goods, food and money and threatened the inhabitants. At Rugby in 1644 troop violence was so bad that four 'abusive fellowes for their ill behaviour' were punished at Coventry (TNA: SP 28/186/5 f3v). The reason for Purefoy's harsh treatment of civilians in the area around Tysoe is not hard to explain. This was royalist country, far from the centres of parliamentarian strength at Coventry, Birmingham and Warwick. Tysoe itself was under three miles from the royalist garrison at Banbury Castle, governed by the young William Compton, brother of the Earl of Northampton, who, like his siblings, was a royalist officer. Purefoy struggled to raise military taxes to support his garrison because some inhabitants, such as those at nearby Butlers Marston, also paid military taxes to 'his Majesty's garrison' at Banbury (TNA: SP 28/183/12). Many south-Warwickshire inhabitants in the area were the Earl's tenants, and parishes there were dominated by royalist and high-Anglican or Catholic families: the Underhills of Idlicote, the Clarkes of Oxhill and Tysoe, the Sheldons of Long Compton and Whichford and the Bishops of Brailes. It was to this safe royalist area that Archbishop Juxon 'retired' from London in the 1640s, celebrating Anglican services in the area unmolested until he resumed his appointments at the Restoration, and there is later evidence from Tysoe of sympathy for, and probably active adherance to, catholicism. For Purefoy, terror and threat were his weapons of choice to counter royalist support amongst a naturally hostile population. Thomas Tasker's and Elizabeth Clarke's claims were made in the form of formal petitions rather than the normal bills of individuals, and this potentially opened up direct channels of communication with the parliamentary County Committee and through them with the central accounts committee in London established in February 1644. As Ann Hughes has shown, this central committee was composed of mainly moderate 'Presbyterians', 'increasingly opposed to military dominance' and eager for 'potential evidence for the misdeeds of rival parliamentarians'. The two Tysoe petitions highlighted George Purefoy's tyrannical rule including imprisonment, threats, torture and illicit quartering and plundering. This was certainly 'potential evidence' of 'misdeeds'. What is perhaps more surprising is that Tysoe's 'Account' is the only one in this south-Warwickshire area to detail such incidents. There are rare references to threat and imprisonment in some of the north Oxfordshire parishes under George Purefoy's control (TNA: SP 28/43) but in the Warwickshire villages around Tysoe with extant 'Accounts' (Oxhill, Idlicote, Brailes, Pillerton Priors and Whichford) although they reported the same heavy parliamentary taxation, burdensome quartering and demands for forced labour there are no references to the tyranny, threat, torture and frequent imprisonment described in Tysoe. There was no obvious reason why the Tysoe inhabitants should have been singled out for particularly harsh treatment so were they unlucky, or particularly brave to submit such detailed claims of injustice? Were they counting on support from the Earl of Northampton, the royalist garrison at Banbury or the King at Oxford to exact revenge? It was more likely that, having been identified by Purefoy as inhabitants of a 'base Malignant' place, they had nothing to lose by calling attention to his tyrannical behaviour in anticipation of justice from the central Committee of Accounts, punishment for Purefoy and restitution for their suffering and losses, events that never in fact came to pass. Maureen Harris researched the relationship between Warwickshire clergy and parishioners between 1660 and 1720 for her PhD from the University of Leicester (2015) and has since published articles and chapters on this theme. She collaborated on the ‘Battle-scarred’ exhibition at the National Civil War Centre and between 2018 and 2020 devised and led a volunteer project to transcribe all the known Warwickshire ‘Loss Accounts’, now available on a publicly-accessible database. She is currently editing them for a Dugdale Society volume. Further Reading Ann Hughes: '"The Accounts of the Kingdom": Memory, Community and the English Civil War', Past and Present, 230: 11 (2016), pp. 311-329. Ann Hughes: 'Diligent enquiries and perfect accounts: central initiatives and local agency in the English civil war', in Chris R. Kyle and Jason Peacey (eds), Connecting Centre and Locality: Political Communication in Early Modern England (Manchester: 2020), pp. 116-132. Philip Tennant, Edgehill and Beyond: The People's War in the South Midlands 1642-1645, Banbury Historical Society, 23, (Stroud: 1992). John Wroughton, An Unhappy Civil War: the Experiences of Ordinary People in Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire, 1642-1646 (Bath: 1999, 2000).

Read More

‘Battle-Scarred’: The Civil War Petitions Summer School

From 10 to 15 July 2022, the Civil War Petitions team ran a residential summer school at Oxford’s historic Merton College, once home of the royal court of Queen Henrietta Maria. The team were joined by a number of guest experts and together, they introduced members of the public to some of the most recent scholarship on the consequences and legacies of the British Civil Wars. Combining lectures, lively Q&A sessions, practical workshops, a battlefield tour and a guided visit to the National Civil War Centre, the programme aimed to showcase some of the results of the Civil War Petitions project. In this week's blog, Denise Greany, a student on the summer school, reports on her experiences of the summer school... The dreaming spires of Merton College, Oxford, on a summer’s afternoon may seem like an incongruous setting for a summer school focused on the often harrowing tales of the men and women petitioning successive governments for aid after the British Civil Wars. No amount of sunshine and wandering through peaceful gardens can soften a sense of the pains described, for instance, by Johane Illery, whose family was threatened and possessions plundered after her husband was executed after the fall of Hemiock Castle, or Edward Bagshaw whose life surgeons saved by removing nine bones from his head wound and who afterwards ate and drank through a hole in the side of his face. But Oxford was not just a beautiful setting for this summer school attended by a group from a wide range of professions and hailing from all over Great Britain and the United States. As the royalist capital during the civil war, it played a central role in events and our studies were lifted from the page and onto its streets. We followed a guide who helped us to reimagine a busy shopping centre as the location of Queen Henrietta Maria’s flower-strewn reunion with Charles I on her return from Europe with soldiers and equipment purchased by selling the crown jewels. From the King’s headquarters at Oxford we travelled to the battlefield of his last stand. We walked the fields at Naseby, following the movements of his dashing cavalry commander Prince Rupert of the Rhine and were treated to a surprise meeting with one of Colonel Okey’s dragoons, whose hedge-hidden firepower helped Parliament’s New Model Army to victory. The power of storytelling emerged clearly throughout the week. Dr Hannah Worthen and Dr Stewart Beale showed us how skilfully both humble and elite widows fashioned themselves as pitiful and deserving cases whilst simultaneously reminding the court of its obligation to recompense such sacrifice. In small group workshops we noticed how selectively petitioners recalled their civil-war experiences long after the fighting had ended. In 1683, John Walpole of Skillington asked for help in his old age, but, as his keen-eyed neighbours stressed, his story left out his ‘king-catching’ antics in the service of Cromwell or, as they now called him, ‘Old Noll’. Printed stories were also powerful weapons for both sides. Prof Mark Stoyle described how the popular press, and its widely-read accounts of dangerous, knife-wielding, irish women and witches flying into battle above the King’s armies, was a contributing factor in the horrifying maiming of female camp-followers after the battle of Naseby. Dr Ismini Pells introduced us to a hero of Parliament’s New Model Army, Philip Skippon, whose remarkable recovery from grievous bullet wounds evidences effective surgical practice, grounded in a body of evidence-based medical knowledge that was described further in fascinating detail by Prof Stephen Rutherford. The group had the opportunity to look closely at the weapons used to inflict these injuries in an inspiring visit to The National Civil War Centre in Newark. In compelling detail, this course used civil war petitions to conjure seventeenth-century legal and medical practices, as well as battles and sieges, through the voices of ordinary men and women so often missing from history.

Read More

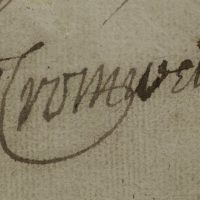

The Persistent Petitioner: Mary Burden, Oliver Cromwell and the Wiltshire Justices of the Peace

In an earlier blogpost on the Civil War Petitions website, David Appleby charted the tenacious efforts of a maimed soldier, William Gray of Braintree in Essex, to secure a pension from the interregnum authorities. Gray’s petitioning labours are impressive, but they are mirrored and even outshone by the resolve and persistence of a widowed mother from Wiltshire, Mary Burden, who petitioned the local bench for welfare relief on no fewer than seven occasions in the 1650s. Burden was even able to call on the support of Oliver Cromwell in her efforts to secure financial support following her husband’s death in military service. A previous blog by Ismini Pells highlighted Cromwell's support for the military pension scheme, but what did this support actually mean to those petitioners like Burden who endeavoured to secure a pension? Lloyd Bowen investigates... Our petitioner was born Mary Comley. She married William Burden in the Wiltshire market town of Corsham on 27 May 1638. Corsham was in a part of the county which had prospered through the wool and cloth industry, although this sector of the economy had seen something of a downturn in recent decades. It is possible that William Burden was involved in the clothing business as his wife would later describe his substantial investment in ‘goods & merchandizes’, by which she may have indicated cloth and fabrics. Civil war swept through England as William and Mary were starting a family: their first child was born only nine months after their nuptials and in a petition of 1656 Mary mentioned her six surviving children. We do not have evidence to show that William Burden served in the first or second civil wars, although it seems likely that he did so. However, in 1649 he ‘tooke up armes for the parliament’ and joined the New Model forces which sailed for Ireland. He became a captain in Colonel Petty’s regiment under Lord General Cromwell, and his wife claimed that, ‘coming newly to his troope’, he laid out some £100 ‘in horses for the state’. This substantial outlay suggests that Burden was a man of some substance and means. Venturing out from his garrison, however, William Burden was caught in up in an unidentified encounter with Irish forces, suffering ‘divers hurts & bruises by meanes whereof he dyed’. Mary’s eldest child at this point was only ten years old, and the family faced a hard and uncertain future. Mary Burden clearly struggled to maintain her family and needed support. In November 1650 she appears (as ‘Mary Burdon’) as one of a plethora of widows whose petitions for relief were referred by the Rump Parliament to the Committee of the Army for consideration. Perhaps her representation was brought before the House by a useful intermediary: could this have been Cromwell himself? We do not know what happened with Mary’s petition on this occasion, but she was evidently not satisfied with whatever resolution was made on her behalf. Thus it was in 1652 that she turned for help and assistance (perhaps once more, perhaps for the first time) to the most powerful man in the country: her husband’s sometime commanding officer, Oliver Cromwell. In October of that year, the Wiltshire justices recorded the lamentable estate of Mary Burden whose case had been recommended to them by the Lord General. We do not possess Mary’s petition to Cromwell (she later claimed that the sessions’ clerk lost or mislaid his order thereon), but he was an officer who took a keen interest in the welfare and support of his troops and their families. Indeed, in February 1652 the Wiltshire bench received a directive from Cromwell that ‘ye widdowes and orphants of those whose husbands and fathers have died … should be alowed a competent pencion in the respective counties where such souldiers inhabited or tooke up armes’. Despite the ordinances in place to ensure that these groups received sufficient support, Cromwell complained that many worthy cases had been refused by local JPs, and that many men and women where thereby ‘exposed to greate extreamity’. Perhaps with these phrases ringing in their ears, the local justices must have been impressed with the strings of patronage that Mary had managed to pull in her own case. Consequently, they awarded her a substantial payment of £10, although this was a single gift and not the pension which Mary evidently desired. As a result of failing to meet her ongoing needs, in April 1653 Mary submitted the first of her many petitions to the Wiltshire county bench when it met at Devizes. A substantial document, she presented herself as the widow of ‘Captayne William Burden’, and told the narrative of her husband venturing to Ireland with £120 in goods which he transported apparently in the hope of selling them there, and that, because she had received no payment for these goods, which were apparently secured on credit, she ‘cannot safely stay at home to manage any maner of dealing for feare of being arrested’. She also made sure to mention the big guns she had in her representational arsenal: Cromwell’s earlier recommendation of her case which was being held on file by the county clerk Francis Swanton, and which, she averred, directed the justices to give her a ‘competent maintenance … until such tyme as the parliament should settle upon her some yearely livelywhood’. A difference arose, however, between Mary Burden on the one hand and the Wiltshire justices on the other over the meaning of Cromwell’s directive that Burden should receive a ‘competent maintenance’. Mary evidently felt that this was a commitment to an annual pension, but the JPs had a very different interpretation. Rather than a considerable ongoing commitment, they felt that they had discharged their duty to her with a substantial gratuity. Despite these differences, and perhaps mindful of Cromwell’s looming presence in the matter, the justices nevertheless resolved to award Mary another single payment of £10. However, their irritation with her presumption in petitioning them so soon after receiving a considerable sum, seems evident in their ruling that she should only receive her payment after all other pensions in the county were satisfied first: Mary Burden was not to take any of the monies which were required to meet the county’s commitments to its regular body of pensioners. A year later, in April 1654, Mary Burden once again appeared with a petition at the Devizes sessions. She had recently been arrested and was currently languishing in prison – she had not received bail and was only appearing before the justices under sufferance. Mary had been arrested for non-payment relating to those goods which her husband had ‘adventured’ into Ireland. Perhaps emboldened by her desperate situation (in addition to her own predicament, Mary described her household as ‘being sick’), Mary attempted a piece of historical revisionism. She asserted that in February 1652 the justices had granted her a pension of £10 per annum rather than the single payment which was, in fact, the case, and she now requested that this pension be paid ‘to supply her present necessity’. The magistrates do not seem to have been impressed, however, and no order of any kind was forthcoming. Undeterred by this setback, and given greater urgency by the fact that she herself had now fallen lame and sick, Mary attended the Marlborough sessions in October 1654 with a new appeal. She again rolled out Cromwell’s recommendation of her case and begged the justices for ‘an yerely pencion according to the … Lord Generalls letter & the late ordinances of parliament’. Mary was clearly a canny operator and was looking to raise the spectre not only of (now Lord Protector) Cromwell’s particular interest in her case, but also his more general concern, as expressed in his February 1652 directive, that needy widows such as herself be relieved by the local authorities. However, the JPs again refused to fall for her claim that Cromwell had authorised her an annual pension, and the fact that they were running out of patience with her continued demands is indicated by their order that she be awarded £5, ‘& she [is] not to expect any more for the future to be payd unto her by the treasurer’. They evidently hoped that this would draw a line under the matter and that they would no longer be troubled by Widow Burden. Some chance! Six months later, in April 1655, Mary was once more at Devizes petitioning the sessions and claiming Cromwell’s authority for an annual pension of £10 which ‘hath bin wholy detained from her’. The sessions order book reveals the justices’ exasperation, noting that she had been allowed several previous payments and had ‘often promised to be contented therewith’; but she kept coming back with Cromwell’s name in her mouth! She was again awarded £5, ‘promiseinge to be troublesome noe further in this kynde’. It seems that this should be the end of her story, but after the apparent stop put on her representations to the Wiltshire sessions, Mary resolved to return to the patronage well which had worked for her previously. She journeyed to London and somehow once more found Cromwell’s ear, likely telling him her piteous story of service, widowhood, indebtedness and imprisonment, and likely also of her frustrations with the Wiltshire bench. And once again Cromwell intervened on her behalf. On 4 July 1655 he ordered that Mary, as the widow of ‘Captaine William Bourden’, should receive a ‘competent pention’ from the Wiltshire sessions to maintain herself and her numerous children. His order, sent from Whitehall and surmounted by ‘Oliver P’ survives as the first document in the ‘Autograph Book’ compiled from notable records found among the quarter sessions rolls (or ‘Great Rolls’) in the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre. Faced with the Lord Protector’s direct order, the justices allowed Mary another interim payment of £5, and directed that her case be considered further at the justices’ Easter meeting. So it was that in April 1656, after some difficulty with submitting the order to the sessions clerk, Mary demanded that her pension be confirmed, ‘that she may not any more be necessitated to travell either to him [Cromwell] or hither [to the sessions]’. Cromwell’s intervention secured Mary Burden an annual pension of £4. She had finally achieved a degree of secure financial support. Surely the Wiltshire justices could now rest easy. Of course they couldn’t! In October 1656 Burden presented a substantial petition to the Wiltshire justices lamenting the small amount she had been awarded, ‘which … cannot be a compitent pencion for the maintenance of her selfe and children’. Mary further maintained that she had not received a promised parcel of land in Ireland which was her husband’s debenture settlement from the Army and, moreover, that she was deeply indebted because of ‘many grevouse suits in lawe and … likewise [the] very tediouse sicknesse that it hath pleased God to inflict uppon her familie’. She thus asked the bench to augment her pension, a task it referred to Colonel William Eyre who was directed to examine what monies had been given to her previously and, who, if he saw fit, was to provide for a modest augmentation that should not exceed £5. The indefatigable Mary Burden’s petitioning story was not quite finished, however. Her constant entreaties and her refusal to act the demure and silent role of a grateful widow had likely alienated many of the justices. Moreover, they cannot have enjoyed having their orders crossed by a woman who could bring the Lord Protector into the equation. Thus it was in a review of pensions in north Wiltshire in October 1657 that, for reasons which are not recorded, the bench decided to stop Mary’s pension altogether, a mere eighteen months after it had been granted. In desperation she petitioned the bench for a final time in April 1659, ‘in a very lowe condicion’ and drowning in debt. She requested that her pension arrears be paid and that the award be reinstated ‘for her releife’. Instead, she received a single donation of forty shillings. The Restoration, of course, put paid to any hopes Mary Burden may have had of continued support from Wiltshire’s pension pot. Cromwell’s name was now anathema rather than a totem which might unlock the coffers of local welfare. We do not know how Mary fared with her debts and the challenges of single motherhood. She died, still a widow, in March 1678 and was buried in Corsham. Her life is poorly documented beyond her petitions, but these reveal a remarkably determined and resourceful woman. She was unflagging in her efforts to secure financial support for herself and for her family. Her case also reveals how resources of central patronage could be leveraged to apply pressure to local authorities in cases of military welfare. Return petitioners were not necessarily uncommon among the widowed and maimed of the civil wars, but Mary Burden’s seven petitions in six years constitute an unusual archive of dogged and tenacious resolve. Further reading Imogen Peck, ‘The Great Unknown: The Negotiation and Narration of Death by English War Widows, 1647-60’, Northern History, 53:2 (2016), pp. 220-235. David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion: Popular Politics and Culture in England, 1603-1660 (Oxford, 1985). Hannah Worthen, ‘Supplicants and Guardians: The Petitions of Royalist Widows during the Civil Wars and Interregnum, 1642–1660’, Women’s History Review, 26:4 (2017), pp. 528-40. John Wroughton, An Unhappy Civil War: The Experiences of Ordinary People in Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire, 1642-46 (Bath, 1999).

Read More

‘The hungry jaws of want’ – Basing House and the Maw of War