John Balshaw’s Jigge: Singing, Star-Crossed Lovers and Signing a Civil War Petition

Some years ago, Jenni Hyde found herself sitting in the British Library reading room looking at a seventeenth-century jigge. Probably best thought of as an early modern musical, jigges were small-scale theatrical entertainments in which the story was told entirely through song. Each scene was set to the tune of a ballad, the popular songs of the early modern period which required no musical training to sing. However, as she soon discovered, this particular jigge was a rather unusual one with quite a story behind it…

Jigges had been particularly popular during the Elizabethan period, but the jigge that I uncovered in the British Library was a very late example of the genre given that it wasn’t written until after the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. In my critical edition of the text, I point out that this is only one of the reasons it is especially noteworthy. Another is that it is the only extant jigge which deals explicitly with political themes – the impact of the Civil Wars on small rural communities.

Town House, which stands on the site of John Balshaw’s home ©Jenni Hyde

But although I knew the name of the jigge’s author, John Balshaw, he proved to be quite elusive. He’s not up there with the great early modern playwrights like William Shakespeare and Aphra Behn. He’s not even an oft-overlooked dramatist like Mary Wroth, whom my Lancaster colleague Alison Findlay has done so much to bring back into the limelight. In fact, as far as we know, this was the only theatrical work that Balshaw wrote. We can’t even be sure that it was ever performed. We really don’t know anything for certain apart from his name and where he lived. We know that he composed the jigge in the small Lancashire village of Brindle, because he says so at the end of the manuscript. I was therefore fascinated to discover only in May 2023 that Balshaw appears on the Civil War Petitions site, supporting the 1676 petition of another Brindle resident, Thomas Hilton, for a military pension.

Artist’s impression of Lathom House at the time of the Civil Wars (Image credit: Wikipedia, reproduced under a Creative Commons licence).

Set in the dying days of the Interregnum, Balshaw’s jigge is a Romeo and Juliet type of story, albeit with a happy ending. The families of the star-crossed lovers are not Montague and Capulet, but Royalist and Parliamentarian, although it has to be said that the hero and heroine themselves remain loyal to King Charles II throughout. Balshaw’s character names hint at his own allegiances. The Royalists are called Trueman, while the Parliamentarians are called Causeless! This is not particularly surprising, as Brindle was a Royalist area throughout the Civil Wars. The community even had a new parliamentarian vicar imposed because their own incumbent, Edward Rigby, was away taking part in the siege of Lathom House near Ormskirk, Lancashire, attempting to defend this Royalist stronghold from Parliament’s forces. We can only speculate on how well the new pastor’s Presbyterian beliefs went down in Brindle, where many residents, like Balshaw, clung to the Roman Catholic faith. It is interesting, in fact, that in the same year that Balshaw appeared as a witness to Thomas Hilton’s infirmity, the recusant rolls show that a John Balshaw from Brindle was fined for not attending church. Nevertheless, we also know from the parish church registers that a John Balshaw was buried in Brindle in 1679. I think, although I cannot prove it, that these John Balshaws were the author of the jigge.

What is fascinating for me, though, is less Balshaw’s relative obscurity as an author than the way that he brings into his jigge so many of the problems that the Civil Wars caused for local communities. Captain Causeless started life as a ploughman, but before the piece begins he has been rewarded for his service in Cromwell’s army with lands confiscated from a Royalist ‘delinquent’. Although he now has at his command ‘poor peasants, rich yeomen and gentry likewise’, he lacks the social standing (and indeed, the wealth) of the traditional landed gentry. Trueman is, or was, the affluent local Justice of the Peace, until his loyalty to the king sees him threatened with sequestration, a process of asset stripping in which the king’s supporters’ lands were confiscated by parliament. So Balshaw’s jigge reflected common concerns about the ‘world turned upside down’ of the Civil War period. The deciding factor in the happy ending to the story is the return of Charles II from exile. Contemporary pamphlets complained about how the traditional local elites were undermined by base-born opportunists, who owed their positions solely to their allegiance to parliament. In fact, so central to the plot is the royalist/parliamentarian divide that I was frankly surprised that none of the scenes were set to the tune of the famous Royalist ballad The King Enjoys His Own Again.

Moreover, given that Balshaw describes himself in the jigge’s dedication as an ‘old decayed poet, new fallen in amongst the beggars’, I suspect this theme of fortune’s ups and downs and its impact on both wealth and social status was particularly resonant to both John Balshaw and his audience. Obviously, the horrors of war were real for those people who took up arms either for king or parliament, but the impact of the Civil Wars was felt much more widely. The economic effects of the wars were enormous, not only in terms of the number of men killed (which is famously higher as a percentage of the population than the casualties of the First World War), but also in terms of those men who returned to rural communities unable to work because of their injuries.

Thomas Hilton’s petition to the Wigan Quarter Sessions in January 1676 would seem to bear this out. Hilton was a labourer, but his war wounds meant that he was in a ‘deplorable condition’. Having fought under the command of one of the leading Lancashire Catholics, Sir Thomas Tyldesley, in a skirmish near Chester, he had sustained a bullet wound to the chest and indeed, the bullet still remained in his breast. Moreover, his leg had been broken in several places and he had several other wounds. Among the men who supported his petition for a pension from the king were some of the key members of the Brindle community. William Gerrard was presumably descended from the Gerrards who had once held the manor of Brindle, which the family sold in 1582 to pay their fines as recusants who refused to attend the Church of England.[1] Interestingly, although the 1673 Michaelmas hearth tax returns for the parish include several Gerrards, William is not one of them.[2] Nevertheless, several of the men who endorsed Hilton’s petition appear in the lists. William Bennett, William Hilton and Thomas Hilton himself appear consecutively in the return, only a few entries down from Balshawe House. Thomas Sharrocke, another of Hilton’s supporters, also appears in the list. All five properties had a single chargeable hearth – indeed, so did the majority of properties in the village. Although Hilton’s petition appears to be signed by Thomas Bailson, I suspect that Thomas simply forgot to cross his ‘t’ – there are many Baitsons in the local area at the time!

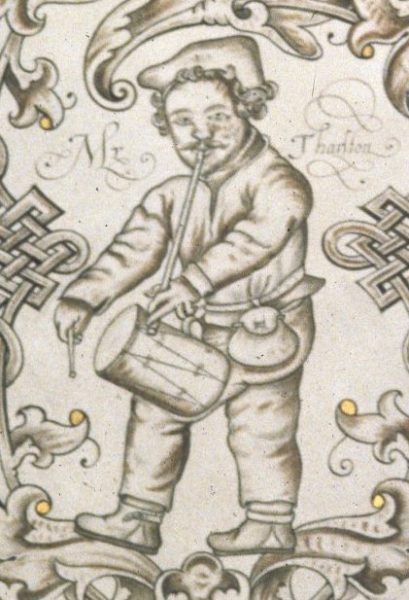

A jigge being performed by Richard Tarleton, a well-known author of jigges during the sixteenth-century (image credit: Wikipedia, reproduced under a Creative Commons licence).

As part of the 50th anniversary celebrations for Lancaster University’s award-winning Regional Heritage Centre, I was asked to stage what we believe to be the world premiere of the jigge in Brindle on 17 June 2023. The performance begins at 7pm with a short talk to set the jigge in its historical context. The musical itself consists of a prologue, which I will perform, followed by four scenes, each of which is set to a different ballad tune which was popular at the time that Balshaw wrote his jigge. With a cast from across the university, including students from History, English Literature and Creative Writing, Computing, Sociology, and Linguistics, supported by actors and musicians from the early music ensemble Passamezzo, we hope to bring John Balshaw’s Jigge to life, and give modern audiences a sense of what this piece might have sounded like.

Balshaw’s story revolves around a girl, Lucina, who has been cheated out of her inheritance by her wicked, Parliamentarian uncle, Captain Causeless. Although it is unclear from the text, it would seem that Lucina’s parents are dead, and were presumably Royalists. Her love interest, Samwell Trueman, is the son of the local Justice of the Peace. I suspect that probably this is a courtesy title rather than reflecting his actual position, as many Royalists were stripped of their roles as community officials during the Interregnum. In order to shore up the fortunes of both families, the Captain cooks up a plot to marry his daughter, Juviana, to Samwell. He sells this to the Justice as a way to prevent the confiscation of his lands. Lucina disguises herself as a serving maid in order to keep tabs on Juviana’s attempts to seduce Samwell, and the servant Bobbe introduces an element of farce to the proceedings as he laments for his previous relationship with Juviana while he reports to the Captain how well the romance is (or rather isn’t) advancing. The Justice, meanwhile, has no intention of marrying his son to one of ‘baser blood’, and is mightily relieved to hear that Bobbe might hold the key to calling off the contract. In the event, however, it is the return of the king that up-ends the proceedings, as Lucina is restored to her lands and the Causlesses are exiled for their deception.

Although we are unsure whether the jigge has ever been performed in the past, we think that if it had been, the performance would have taken place in one of the local gentry homes. Our performance will take place in Brindle’s Community Hall, close to the Parish Church which has stood on that site since Balshaw’s time. Thomas Hilton’s petition to the Quarter Sessions adds another layer of local knowledge to the jigge – as I suspected all along, I now know that the residents of Brindle knew first-hand how devastating the effects of the Civil Wars could be.

Brindle Parish Church and the Cavendish Arms ©Jenni Hyde

[1] ‘The parish of Brindle’, pp. 75-81 in William Farrer and J. Brownbill (eds.), A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 6 (London, 1911) via British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol6/pp75-81 [accessed 29 May 2020].

[2] I am grateful to Andrew Wareham of the Centre for Hearth Tax Research at Roehampton University for supplying me with the 1673 Lancashire hearth tax returns transcript ahead of its publication on Hearth Tax Digital, https://gams.uni-graz.at/context:htx [accessed 19 May 2023].

Dr Jenni Hyde is a Trustee of the Historical Association and Lecturer in Early Modern History at Lancaster University. Her first book, Singing the News: Ballads in Mid-Tudor England, was published in 2018 by Routledge while her critical edition of a seventeenth-century ‘musical’, John Balshaw’s Jigge: Revelry and Royalism in Restoration Lancashire, appeared in 2021. She is a former music teacher, a classically-trained soprano and a keen folk singer.

Further Reading

Stephen Bull, ‘A General Plague of Madness’: The Civil War in Lancashire (Lancaster: Carnegie Press, 2009)

Roger Clegg and Lucie Skeaping, Singing Simpkin and Other Bawdy Jigs (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2014)

Jenni Hyde, John Balshaw’s Jigge: Revelry and Royalism in Restoration Lancashire (Lancaster: Lancaster University Regional Heritage Centre, 2021)