The Persistent Petitioner: Mary Burden, Oliver Cromwell and the Wiltshire Justices of the Peace

In an earlier blogpost on the Civil War Petitions website, David Appleby charted the tenacious efforts of a maimed soldier, William Gray of Braintree in Essex, to secure a pension from the interregnum authorities. Gray’s petitioning labours are impressive, but they are mirrored and even outshone by the resolve and persistence of a widowed mother from Wiltshire, Mary Burden, who petitioned the local bench for welfare relief on no fewer than seven occasions in the 1650s. Burden was even able to call on the support of Oliver Cromwell in her efforts to secure financial support following her husband’s death in military service. A previous blog by Ismini Pells highlighted Cromwell’s support for the military pension scheme, but what did this support actually mean to those petitioners like Burden who endeavoured to secure a pension? Lloyd Bowen investigates…

A seventeenth-century weaver’s workshop by Cornelis Gerritsz Decker, 1659 (image from the Rijksmuseum, reproduced under a Creative Commons licence).

Our petitioner was born Mary Comley. She married William Burden in the Wiltshire market town of Corsham on 27 May 1638. Corsham was in a part of the county which had prospered through the wool and cloth industry, although this sector of the economy had seen something of a downturn in recent decades. It is possible that William Burden was involved in the clothing business as his wife would later describe his substantial investment in ‘goods & merchandizes’, by which she may have indicated cloth and fabrics. Civil war swept through England as William and Mary were starting a family: their first child was born only nine months after their nuptials and in a petition of 1656 Mary mentioned her six surviving children.

We do not have evidence to show that William Burden served in the first or second civil wars, although it seems likely that he did so. However, in 1649 he ‘tooke up armes for the parliament’ and joined the New Model forces which sailed for Ireland. He became a captain in Colonel Petty’s regiment under Lord General Cromwell, and his wife claimed that, ‘coming newly to his troope’, he laid out some £100 ‘in horses for the state’. This substantial outlay suggests that Burden was a man of some substance and means. Venturing out from his garrison, however, William Burden was caught in up in an unidentified encounter with Irish forces, suffering ‘divers hurts & bruises by meanes whereof he dyed’. Mary’s eldest child at this point was only ten years old, and the family faced a hard and uncertain future.

Mary Burden clearly struggled to maintain her family and needed support. In November 1650 she appears (as ‘Mary Burdon’) as one of a plethora of widows whose petitions for relief were referred by the Rump Parliament to the Committee of the Army for consideration. Perhaps her representation was brought before the House by a useful intermediary: could this have been Cromwell himself?

We do not know what happened with Mary’s petition on this occasion, but she was evidently not satisfied with whatever resolution was made on her behalf. Thus it was in 1652 that she turned for help and assistance (perhaps once more, perhaps for the first time) to the most powerful man in the country: her husband’s sometime commanding officer, Oliver Cromwell. In October of that year, the Wiltshire justices recorded the lamentable estate of Mary Burden whose case had been recommended to them by the Lord General. We do not possess Mary’s petition to Cromwell (she later claimed that the sessions’ clerk lost or mislaid his order thereon), but he was an officer who took a keen interest in the welfare and support of his troops and their families. Indeed, in February 1652 the Wiltshire bench received a directive from Cromwell that ‘ye widdowes and orphants of those whose husbands and fathers have died … should be alowed a competent pencion in the respective counties where such souldiers inhabited or tooke up armes’. Despite the ordinances in place to ensure that these groups received sufficient support, Cromwell complained that many worthy cases had been refused by local JPs, and that many men and women where thereby ‘exposed to greate extreamity’. Perhaps with these phrases ringing in their ears, the local justices must have been impressed with the strings of patronage that Mary had managed to pull in her own case. Consequently, they awarded her a substantial payment of £10, although this was a single gift and not the pension which Mary evidently desired.

Oliver Cromwell by Robert Walker c. 1649, the year Cromwell led the New Model Army – and Captain William Burden with it – to Ireland (image from National Portrait Gallery, reproduced under a CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 licence).

As a result of failing to meet her ongoing needs, in April 1653 Mary submitted the first of her many petitions to the Wiltshire county bench when it met at Devizes. A substantial document, she presented herself as the widow of ‘Captayne William Burden’, and told the narrative of her husband venturing to Ireland with £120 in goods which he transported apparently in the hope of selling them there, and that, because she had received no payment for these goods, which were apparently secured on credit, she ‘cannot safely stay at home to manage any maner of dealing for feare of being arrested’. She also made sure to mention the big guns she had in her representational arsenal: Cromwell’s earlier recommendation of her case which was being held on file by the county clerk Francis Swanton, and which, she averred, directed the justices to give her a ‘competent maintenance … until such tyme as the parliament should settle upon her some yearely livelywhood’.

A difference arose, however, between Mary Burden on the one hand and the Wiltshire justices on the other over the meaning of Cromwell’s directive that Burden should receive a ‘competent maintenance’. Mary evidently felt that this was a commitment to an annual pension, but the JPs had a very different interpretation. Rather than a considerable ongoing commitment, they felt that they had discharged their duty to her with a substantial gratuity. Despite these differences, and perhaps mindful of Cromwell’s looming presence in the matter, the justices nevertheless resolved to award Mary another single payment of £10. However, their irritation with her presumption in petitioning them so soon after receiving a considerable sum, seems evident in their ruling that she should only receive her payment after all other pensions in the county were satisfied first: Mary Burden was not to take any of the monies which were required to meet the county’s commitments to its regular body of pensioners.

A year later, in April 1654, Mary Burden once again appeared with a petition at the Devizes sessions. She had recently been arrested and was currently languishing in prison – she had not received bail and was only appearing before the justices under sufferance. Mary had been arrested for non-payment relating to those goods which her husband had ‘adventured’ into Ireland. Perhaps emboldened by her desperate situation (in addition to her own predicament, Mary described her household as ‘being sick’), Mary attempted a piece of historical revisionism. She asserted that in February 1652 the justices had granted her a pension of £10 per annum rather than the single payment which was, in fact, the case, and she now requested that this pension be paid ‘to supply her present necessity’. The magistrates do not seem to have been impressed, however, and no order of any kind was forthcoming.

Undeterred by this setback, and given greater urgency by the fact that she herself had now fallen lame and sick, Mary attended the Marlborough sessions in October 1654 with a new appeal. She again rolled out Cromwell’s recommendation of her case and begged the justices for ‘an yerely pencion according to the … Lord Generalls letter & the late ordinances of parliament’. Mary was clearly a canny operator and was looking to raise the spectre not only of (now Lord Protector) Cromwell’s particular interest in her case, but also his more general concern, as expressed in his February 1652 directive, that needy widows such as herself be relieved by the local authorities. However, the JPs again refused to fall for her claim that Cromwell had authorised her an annual pension, and the fact that they were running out of patience with her continued demands is indicated by their order that she be awarded £5, ‘& she [is] not to expect any more for the future to be payd unto her by the treasurer’. They evidently hoped that this would draw a line under the matter and that they would no longer be troubled by Widow Burden.

Some chance! Six months later, in April 1655, Mary was once more at Devizes petitioning the sessions and claiming Cromwell’s authority for an annual pension of £10 which ‘hath bin wholy detained from her’. The sessions order book reveals the justices’ exasperation, noting that she had been allowed several previous payments and had ‘often promised to be contented therewith’; but she kept coming back with Cromwell’s name in her mouth! She was again awarded £5, ‘promiseinge to be troublesome noe further in this kynde’.

It seems that this should be the end of her story, but after the apparent stop put on her representations to the Wiltshire sessions, Mary resolved to return to the patronage well which had worked for her previously. She journeyed to London and somehow once more found Cromwell’s ear, likely telling him her piteous story of service, widowhood, indebtedness and imprisonment, and likely also of her frustrations with the Wiltshire bench. And once again Cromwell intervened on her behalf. On 4 July 1655 he ordered that Mary, as the widow of ‘Captaine William Bourden’, should receive a ‘competent pention’ from the Wiltshire sessions to maintain herself and her numerous children. His order, sent from Whitehall and surmounted by ‘Oliver P’ survives as the first document in the ‘Autograph Book’ compiled from notable records found among the quarter sessions rolls (or ‘Great Rolls’) in the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre. Faced with the Lord Protector’s direct order, the justices allowed Mary another interim payment of £5, and directed that her case be considered further at the justices’ Easter meeting. So it was that in April 1656, after some difficulty with submitting the order to the sessions clerk, Mary demanded that her pension be confirmed, ‘that she may not any more be necessitated to travell either to him [Cromwell] or hither [to the sessions]’. Cromwell’s intervention secured Mary Burden an annual pension of £4. She had finally achieved a degree of secure financial support. Surely the Wiltshire justices could now rest easy.

Of course they couldn’t! In October 1656 Burden presented a substantial petition to the Wiltshire justices lamenting the small amount she had been awarded, ‘which … cannot be a compitent pencion for the maintenance of her selfe and children’. Mary further maintained that she had not received a promised parcel of land in Ireland which was her husband’s debenture settlement from the Army and, moreover, that she was deeply indebted because of ‘many grevouse suits in lawe and … likewise [the] very tediouse sicknesse that it hath pleased God to inflict uppon her familie’. She thus asked the bench to augment her pension, a task it referred to Colonel William Eyre who was directed to examine what monies had been given to her previously and, who, if he saw fit, was to provide for a modest augmentation that should not exceed £5.

The indefatigable Mary Burden’s petitioning story was not quite finished, however. Her constant entreaties and her refusal to act the demure and silent role of a grateful widow had likely alienated many of the justices. Moreover, they cannot have enjoyed having their orders crossed by a woman who could bring the Lord Protector into the equation. Thus it was in a review of pensions in north Wiltshire in October 1657 that, for reasons which are not recorded, the bench decided to stop Mary’s pension altogether, a mere eighteen months after it had been granted. In desperation she petitioned the bench for a final time in April 1659, ‘in a very lowe condicion’ and drowning in debt. She requested that her pension arrears be paid and that the award be reinstated ‘for her releife’. Instead, she received a single donation of forty shillings.

The Restoration, of course, put paid to any hopes Mary Burden may have had of continued support from Wiltshire’s pension pot. Cromwell’s name was now anathema rather than a totem which might unlock the coffers of local welfare. We do not know how Mary fared with her debts and the challenges of single motherhood. She died, still a widow, in March 1678 and was buried in Corsham. Her life is poorly documented beyond her petitions, but these reveal a remarkably determined and resourceful woman. She was unflagging in her efforts to secure financial support for herself and for her family. Her case also reveals how resources of central patronage could be leveraged to apply pressure to local authorities in cases of military welfare. Return petitioners were not necessarily uncommon among the widowed and maimed of the civil wars, but Mary Burden’s seven petitions in six years constitute an unusual archive of dogged and tenacious resolve.

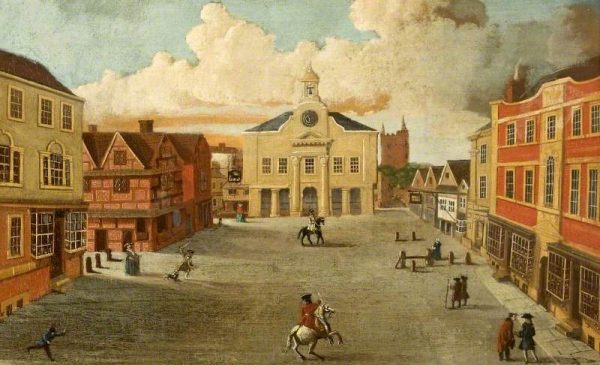

The Yarn Hall in Devizes, meeting place of the Wiltshire Quarter Sessions and site of Mary Burden’s seven petitioning attempts (image from Wikipedia, reproduced under a Creative Commons licence).

Further reading

Imogen Peck, ‘The Great Unknown: The Negotiation and Narration of Death by English War Widows, 1647-60’, Northern History, 53:2 (2016), pp. 220-235.

David Underdown, Revel, Riot and Rebellion: Popular Politics and Culture in England, 1603-1660 (Oxford, 1985).

Hannah Worthen, ‘Supplicants and Guardians: The Petitions of Royalist Widows during the Civil Wars and Interregnum, 1642–1660’, Women’s History Review, 26:4 (2017), pp. 528-40.

John Wroughton, An Unhappy Civil War: The Experiences of Ordinary People in Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire, 1642-46 (Bath, 1999).