‘The hungry jaws of want’ – Basing House and the Maw of War

A siege is one of the cruellest forms of warfare. It turns neighbourhoods into warzones and terrorises local communities. Inside the lines, food and drink, health and hope, even life and death become variables in a mass human experiment that shreds the nerves and saps morale. In her new book about the sieges of Basing House, Jessie Childs recovers the shock of the conflict by following it on the ground, as experienced by various individuals before, during and after the war. In this blog, she demonstrates how petitions are an invaluable resource both in giving a sense of the people behind the statistics and in contributing to a richer picture of the political and military context.

Captain Robert Amery’s regimental commander, Colonel Marmaduke Rawdon (engraving by A. Hertocks, from Wikipedia and reproduced under a Creative Commons licence).

The ‘humble petition of Captain Robert Amery’, for example, submitted in December 1660 and now in The National Archives, adds fresh details to the story of the build-up to war (TNA SP 29/25, fols. 40-42). Amery was a captain in the ‘London Regiment’ of Sir Marmaduke Rawdon in the royalist garrison at Basing House, but before the war he had been a vintner, and before that, a member of the Musicians’ Company. He was critical of the ‘five members’ of parliament, whom Charles I had tried to arrest on 4 January 1642, and he ‘declared against them & their unjust proceedings’ at a city meeting soon afterwards. Amery claims in his petition that he would have been ‘torn in pieces by the rude multitude had he not been rescued & conveyed away from their rage & fury’.

Like many other Londoners, Amery did not hasten to the king’s standard when it was raised at Nottingham on 22 August 1642. Instead, he stayed on in the capital and campaigned for a peaceful settlement. According to his petition, he was ‘employed as chief agent to deliver the petition for peace to Isaac Pennington, then Lord Mayor of London, at the Court of Aldermen. It being cried down and rejected, your petitioner, with others, were in danger of their lives’. There is a real sense of jeopardy here in calling for peace at a time, and in a city, where the momentum seemed to be all for the war.

‘Afterwards,’ Amery continues, he was ‘forced to hide himself for refusing to take up arms for the parliament’ and was ultimately constrained ‘to forsake his house and leave his family in distress’. Sometime in late 1642 or early 1643, he fled to the king’s headquarters in Oxford, ‘where he lay a long time at his great charge’, before joining Rawdon’s regiment and marching forty miles south to Basing House.

John Paulet, 5th Marquess of Winchester and owner of Basing House (engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar from Wikipedia and reproduced under a Creative Commons licence).

‘Loyalty House’, as the royalists called it, was the palatial Hampshire mansion of John Paulet, 5th Marquess of Winchester and his half-Irish wife, Honora. Both were Catholic and their home became not only a royalist garrison, but a civilian refuge. Rumour had it that it was also a depository for royalist treasure. To parliamentarians, it was a bastion of Stuart degeneracy: a ‘limb of Babylon’ that required amputation. It was strategically important because it was almost equidistant from London and Oxford and commanded the main road to the West, but it mattered symbolically too, especially after November 1643, when William ‘the Conqueror’ Waller failed to take it with a much larger force.

Amery’s wife and children eventually joined him at Basing House. They had been ‘so violently persecuted’, in London, he claimed, and harried ‘from place to place, that they suffered exceedingly by abuses & want of maintenance’ and had no option but to escape. They weren’t the only ones. Winchester accused Rawdon of having too many ‘useless mouths’ in his regiment. Rawdon retorted that Winchester had at least three for one in his (Hampshire Record Office, 40 M93/1).

The women were far from useless, however, and during Waller’s assault, the marchioness and her ladies stripped lead from the roof to make musket balls, while others hurled down rocks. A petition submitted in 1665 by one Katherine Haswell (TNA SP 29/113, fol. 173) shows that she, like Katherine de Luke (see Stewart Beale’s blog on Katherine de Luke), acted as an intelligencer. Her father, she claims, ‘was kept during the late rebellion in chains, upon his late Majesty’s account; her brother likewise lost his life at Edgehill’. Haswell herself, ‘after many services upon a royal account in carrying of letters and the like, was dangerously wounded by the rebels at Basing House whereby she is utterly disabled from a livelihood’. She requested that her husband, ‘a foremast man, though formerly an officer’, receive a promotion in the Navy.

‘The rebels’, as the royalists called the parliamentarians, also suffered during their varied attempts to take Basing House, as several petitions unearthed by the Civil War Petitions Project reveal. Jeremiah Maye of Ashdon, Essex, for example, had been impressed into the company of Captain John Smith in the regiment of Sir William Waller. He had taken part in the November assault on Basing House, which had seen many of his comrades burn to death in the farm outhouses or be peppered by case shot in the park. Maye’s injuries are not specified, but were clearly severe: ‘He received divers hurts and wounds in his body, which renders him unfit for future service or any ways able to maintain himself and languishing family, being now in a most sad and deplorable condition.’ Maye begged for a pension, or ‘some present relief’, to save him from ‘the hungry jaws of want’. A certificate survives, stamped with the seal of Oliver Cromwell and dated 10 January 1651[2], desiring ‘a competent weekly pension for his relief and maintenance’. It seems that this was not enough to impress the JPs, who only awarded Maye a one-off gratuity of £2.

The summer of 1644 saw another major attempt on Basing House, this time with a lengthy blockade. Richard ‘Idle Dick’ Norton sat down before the house in June with forces from Hampshire, Surrey and Sussex. Within a month, the siege lines were drawn to within half a musket shot of the house. ‘Continual firing,’ recorded an anonymous diarist inside the house, ‘pouring lead into the garrison, they spoil us two or three a day’. (BL Thomason, E 27/5, p. 5) A letter sent by a Roundhead to London on 5 July reported that the Cavaliers were in serious trouble. ‘Since our throwing up a trench against them, the enemy are very still . . . We hope they cannot long hold out.’ (The Weekly Account, 4-11 July 1644 [E 54/24]).

But the garrison did hold out, all through the summer and into November, when Norton finally raised the siege. According to the anonymous diarist, the garrison was ‘drawn down by length of siege almost unto the worst of all necessities, provision low, the soldiers spent and naked and the numbers few’. But the besiegers were also ‘wearied with lying 24 weeks, diseases, with the winter seizing them’ and their army ‘wasted from 2,000 to 700’. One Sussex captain, serving under Colonel Herbert Morley, was shot dead by a garrison sniper on 20 July. Three weeks later, Morley himself was ‘bored through the shoulder’ while viewing the works in the park (Mercurius Aulicus, 11-17 August 1644 [E 8/20]). Over a decade afterwards, in January 1656, John Doyt, also of Morley’s regiment, petitioned the Sussex JPs for aid, claiming that he had received ‘several wounds’ at Basing House, ‘much to the prejudice of my labour, as will appear upon search by any surgeon’. The appeal was successful. Doyt was allotted 30 shillings upfront and £3 per year.

Another Sussex parliamentarian, Thomas Anstie of Keymer, survived the summer siege, ‘bearing his parts faithfully with his fellows’, only to have an arm ‘shot off with a cannon’ at Weymouth. He was a poor man with a wife and three children, according his certificate (6 October 1645), and seems to have been popular, since seventeen men backed his petition to the Lewes JPs: ‘Our poor do lie very heavy upon us already,’ they conceded, ‘yet we are willing to contribute to his relief’. The support from Anstie’s neighbours seems to have won over the JPs, who awarded the veteran a gratuity of 40 shillings and an annual pension of £4.

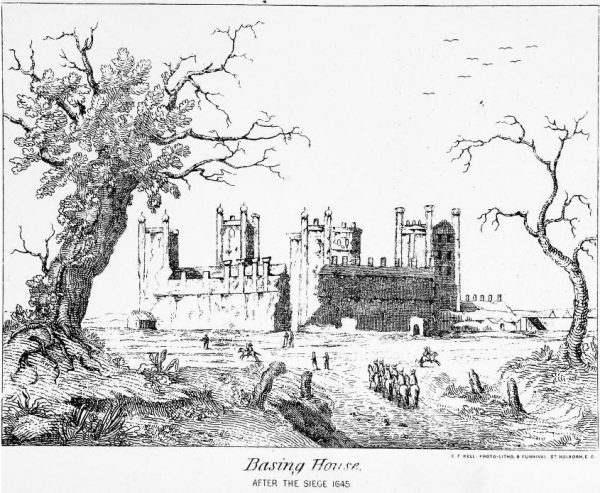

Basing House after the siege from F. J. Baigent & J. E. Millard, ‘A history of the ancient town and manor of Basingstoke in the county of Southampton’ (1889) pp. 428-9 (from Wikipedia and reproduced under a Creative Commons licence).

Eight days later Basing House fell to Oliver Cromwell and some 7,000 troops of the New Model Army. At least 100 defenders were slain in the storming, 100 were taken prisoner and 100 hid in the house’s underground vaults and priest-holes. It has always been assumed that they perished in the fire that blazed through the house afterwards, but three separate London newsbooks state that they re-emerged from their holes two days later.

‘I need not tell you how glad the country people are hereabouts that Basing is reduced to the obedience of the parliament,’ reported a Roundhead from Cromwell’s quarters on the day of the storm (Perfect Passages, 8–15 Oct. 1645 (E 266/2), 408). He was hardly impartial, but it was true that most locals did not mourn Loyalty House. They grieved for lost lives and property, though. The garrison had devoured their crops, grass and wood, and all too often the besiegers had done the same. All those within the manor of Basing itself ‘are so miserably poor that there is nothing from them to be had or expected’, recorded the Hampshire Compounding Committee in 1650 (TNA SP 23/251, no. 132, fol. 272). Francis Ivory of The George Inn, Basingstoke was ‘so insolvent that he dareth not show his head’.

Basing House, as it remains today (Image by Hampshire Cultural Trust: https://www.hampshireculture.org.uk/basing-house).

One more set of appeals are worth a final mention. They were submitted by a royalist widow called Mary Peake to the dean and chapter of Canterbury Cathedral between 1661 and 1666 (Canterbury Cathedral Archives, DCc–CantLet/116, 134, 143; CCA DCc– PET /208, 209). Mary’s late husband had been a cathedral prebendary, and in three letters and two petitions, she documents the trials of her post-war widowhood. On 23 November 1664, she writes of ‘having a long time lien under sickness and lameness’, adding that ‘my age bringing every day with it new diseases and griefs’. She survived ‘the dreadful pestilence’ of 1665, ‘but my poverty is such that unless I be relieved by your wonted charity, I am like to perish’. The following year, she lost everything in the Great Fire of London. Her last surviving letter, dated 29 October 1666 and written from a room in Fetter Lane, explains that ‘all my children’s habitations were burned down to the ground’ and that she was having to share a chamber with another woman, ‘for which I do pay weekly, or else must be outed again’. She had written to the dean since the fire, asking for accommodation within the cathedral precincts, ‘but it seems it has been my unhappiness that my letter came not to your hands, for I have not received any answer to it.’

Mary’s late husband was Dr Humfrey Peake, a royal chaplain as well as cathedral prebendary, ‘who,’ she writes, ‘for his loyalty to his king & master & constant defence of the Church of England, sacrificed both himself & his family’. He had died soon after the storming of Basing House and was related to a senior officer there, the print-seller Robert Peake. It is possible that he witnessed the siege himself. Just before his death, he wrote a little-known book call Meditations upon a Seige [sic.] (1646). It is a first-hand account of siege warfare and clearly the result of some personal experience, indeed trauma. He writes of the ‘sad spectacle’ of death, the ‘intolerable stench’ of it, and the ‘hideous shapes’ of it ever stalking his dreams. It is hard to disagree with his introductory words:

‘Amongst the many ways of enmity, whereby in a declared war men use to express their endeavours to ruin one another: this of a siege is the sharpest and the saddest.’

The Siege of Loyalty House by Jessie Childs was published by Bodley Head on 19 May 2022.