A Vengeful Vicar and a Martyred Mother: The Petition of James Bamlett

It is the job of historians to read all sources critically, an especially important consideration when examining sources from the Civil Wars – an event characterised by bitter rivalries and contested memories. The documents on Civil War Petitions are no exception and provide a useful illustration of the ways political considerations could shape representations of the past. The stories contained in the petitions are permeated with hidden agendas and we should be cautious of taking these tales at face value. However, the claims and counter claims of the petitions are in themselves useful to historians, adding texture and nuance to our existing knowledge of the Civil Wars. In this blog, Mark Stoyle uses the petition of a Devon soldier to shed new light on one of the most well-known publications resulting from the Civil Wars…

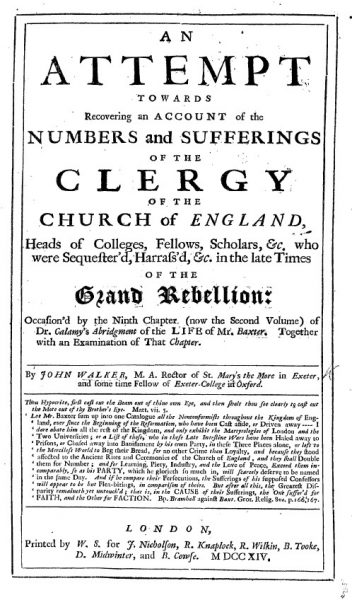

John Walker’s ‘Sufferings of the Clergy’ (1714)

In 1714, John Walker – rector of the parish of St Mary Major in Exeter, and a steadfast Anglican – published the formidable work for which he is still remembered to this day: An Attempt towards Recovering an Account of the Numbers and Sufferings of the Clergy of the Church of England … in the Late Times of the Great Rebellion. As its somewhat ponderous title makes clear, Walker’s Sufferings was intended first, to calculate how many English and Welsh clergymen had been ejected, fined or otherwise ‘Harras’d’ by the enemies of the Crown during the Civil Wars and Interregnum, and second, to memorialise the tribulations that these individuals had undergone as a result of their good affection to the Royalist cause. Among the many hundreds of ‘loyal clergy’ who feature in Walker’s pages is Henry Smith: a man who was born, according to Walker, into a mercantile family at Great Torrington in North Devon, who was educated at the University of Oxford, and who eventually returned to his native county in order to take up a living in the rural parish of Cornwood, on the south-western fringes of Dartmoor. Walker provides a vivid account of Smith’s experiences during the First Civil War, telling us, among other things, that the vicar of Cornwood had been ‘a zealous loyalist’, that he had received ‘the Distinguishing Honour of a Visit from Prince Charles’, and that his Royalism had rendered him ‘very Obnoxious to the [Parliamentarian] Party’. Smith’s house had been ‘plundered by a Party of [Roundhead] Soldiers from the Garrison at Plymouth’, Walker notes, ‘who did not so much as leave him a Dish or a Spoon … [and] at the same time they plundered him of his Books’. Worse was still to come, moreover, for Walker goes on to relate that, after the war was over, Smith had been ‘kept prisoner for a long time, somewhere … about Plymouth … and at length sent to a common Jayl in Exeter, where he died soon after the Martyrdom of his Prince’: in other words, soon after the execution of Charles I in January 1649.

There is no reason to doubt that much of what Walker tells us about Smith is true. Yet while Walker presents the vicar of Cornwood as an innocent abroad – as a hapless man of God who had been mercilessly harried from pillar to post by ‘Barbarous and Inhuman’ persecutors – a petition presented to the Devon justices of the peace half a century before the Sufferings was published paints a rather different picture, and suggests that the harshness with which the county’s post-war Parliamentarian governors had treated Smith may perhaps have reflected the pitiless attitude which he himself had displayed towards a pro-Parliamentarian country-woman at the height of the conflict. In 1648 Edmund Davyes and his fellow JPs, sitting at the general sessions at Exeter Castle, were presented with an unusual petition for redress from a certain James Bamlett, of Cornwood. Bamlett may have been one of Smith’s parishioners, but he had clearly not followed him into the Royalist camp. On the contrary, the Cornwood man informed the justices that ‘your Peticioner hath stoode always well affected towards the parliament’s service and hath bine a souldier in Plymouth dureinge the time of warres’. While he had been serving in the Parliamentarian garrison of Plymouth, Bamlett went on, he had been visited on several occasions by his mother, who ‘did resort there, as [often as] she could find an opportunity [in order] to supply your peticioner’s wants with such necessaryes as he wanted’: in other words, to provide her son with food, clothes and money. Yet these maternal mercy-missions – which must have involved Bamlett’s mother tramping the four miles from Cornwood, which lay deep within Royalist-held territory, all the way to the outworks of Plymouth, and back again – were soon to come to an abrupt end. For shortly after his mother’s ‘retorne to her owne home’ from one such expedition, Bamlett’s petition continues, ‘some notice was taken’ that she ‘had bine in Plymouth, whereuppon she was taken upp’ by a party of Royalist troopers and carried away to ‘the Marshals att Plympton’. This was almost certainly the temporary prison overseen by the provost marshal: the officer who was responsible for overseeing military discipline in the quarters then occupied by the besieging Royalist forces.

Plympton Castle as it appears today (photo credit: Tony Atkin, from Wikipedia, reproduced under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence).

Plympton, which lies just to the north-east of Plymouth, had long been the headquarters of the Royalist troops who had been blockading the Parliamentarian port, on and off, since the conflict began. Nothing is known of the marshal’s prison there, but it may well have stood within the walls of the Norman castle which overlooked the village itself. Here Mrs Bamlett was confined for a period of a month or six weeks, her son’s petition tell us, ‘till she came to her triall, and by that triall was found guiltie, and Condempt to die’. It seems unlikely that a woman would have been brought before a court martial simply for conveying provisions to a relative, so the suspicion must surely be that Mrs Bamlett stood accused of being a spy, who had carried in intelligence to the Roundhead garrison. Whatever the charge may have been, there was clearly at least one person in the Royalist camp who felt that the court’s sentence had been too harsh, for Bamlett goes on to relate that ‘thereuppon one Mistris Church prevailed soe far with Maior Generall Harres as she procured her [i.e. Mrs Bamlett’s] freedome, and paid for her fees [i.e. the charges that she had incurred during her imprisonment] 16 shillings, and thought all had gone on in a faire way, and went to have her out of the Marshal’s [prison]’. The identity of the gentlewoman who had interceded on Mrs Bamlett’s behalf is uncertain, but she may well have been the wife of Captain Edmond Church, a Royalist officer in Colonel Henry Carey’s regiment of horse: a unit which served, for many months, before Plymouth. ‘Maior Generall Harres’ can definitely be identified with Robert Harris of Staddon, in nearby Plymstock – and the fact that James Bamlett’s petition notes that it was to him that Mistress Church had directed her plea strongly suggests that the trial had taken place at some point in 1645, for it is during that year that Harris is known to have assumed overall command of the Royalist forces blockading Plymouth.

As Mistress Church arrived at the prison door to secure the captive woman’s release, it must have seemed to Mrs Bamlett that she had escaped the hangman’s noose. But if so, she had reckoned without the malice of her local pastor, for ‘soe yt ys, may yt please your good worship[s]’, James Bamlett went on to lament:

‘That in the interim one Henry Smith, then Minister of Cornwood, beinge veary powerfull with Generall Harres, prevayled soe farr with him, that order was geven [that] she should not be delivered; but [she] was [instead] brought to the Marshall[’s] Chamber and had there Conference with the said Smith, who then told your Peticioner’s Mother, “That her sonne (meaninge your peticioner) said he would see his [i.e. Smith’s] Coate turned, but now he [i.e. Smith] would see her Coatte turned”, and thereupon [she] was returned to the Marshals [prison] againe, and within a veary short time after was executed, to the great greiffe, and discomfort of your peticioner and other her friends’.

The precise meaning of the words which Henry Smith is alleged to have spoken to Mrs Bamlett in the marshal’s chamber remain a little obscure, but appear to indicate that on some previous occasion – perhaps when the Parliamentarian soldiers had sallied out from Plymouth to plunder Smith’s house? – James Bamlett had been unwise enough to express the opinion that he would live to see the day when the zealously Royalist cleric would be obliged to ‘turn his coat’, or to become a (constrained) Parliamentarian. Now, the vicar of Cornwood appears to have mockingly assured Mrs Bamlett – after he had persuaded Harris to reverse his earlier decision to spare her – he, Smith, would witness her receiving her just deserts – both for her own pro-Parliamentarianism and for her son’s impudence – by being ‘turned off’ at the gallows. Thus James Bamlett’s initial jibe at Smith and the clergyman’s subsequent gloating retort to Bamlett’s mother provide us with excellent illustrations of the way in which martial language began both to infiltrate and to inflect everyday speech during the English Civil Wars.

St Michael’s Church, Cornwood, where Henry Smith was vicar (photo credit: Derek Harper, from Wikipedia, reproduced under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence).

It is hard to doubt that Bamlett’s mother was indeed executed by the Royalist military authorities at Plympton; her son concluded his petition in 1648 by begging the JPs to take his mother’s case ‘into Consideracion and to have the business duly examined, and further to inflict such punishment on … the said Smith as uppon due proffes touching her death shall appeare’. That Smith is said by Walker to have been imprisoned during the post-war period perhaps indicates that the justices did, indeed, seek to indict him for the heartless zeal with which he had pursued poor Mrs Bamlett to her death – and if the vicar of Cornwood did, indeed, die while immured in the common jail in Exeter, as Walker avers, then James Bamlett may well have regarded this as some small recompense for his mother’s own ‘sufferings’. Whether John Walker would have written quite so glowingly of Henry Smith had James Bamlett’s petition lain open before him as he bent himself to his task is something we will never know – but the document certainly raises the possibility that the clerical Royalism which the Exeter clergyman was later to eulogise with such wholehearted enthusiasm may sometimes have had a considerably darker edge to it than his narrative would tend to suggest.

Further Reading

Andrew Hopper, Turncoats and Renegadoes: Changing Sides during the English Civil War (Oxford, 2012).

Fiona McCall, Baal’s Priests: The Loyalist Clergy and the English Revolution (Farnham, 2013).

Mark Stoyle, Plymouth in the Civil War (Devon Archaeology, 7, Exeter, 1998).