Civilian Suffering in the Civil War: the case of Tysoe in Warwickshire

In a previous blog, David Appleby described how the Civil War Petitions team often agonized over which claimants to military welfare to exclude from the project, many of those not making the cut being maimed civilians. Here, Dr Maureen Harris looks at a series of Civil War documents, the ‘Loss Accounts’, which focus specifically on civilians and the suffering caused by their financial and material losses in the First English Civil War (1642-6). As a result of a unique project, volunteers have for the first time transcribed and tabulated all the known ‘Loss Accounts’ for a single county: Warwickshire. The initiative was sponsored by the Dugdale Society with the Friends of the Warwickshire County Record Office and financially supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. Warwickshire has probably the best run of ‘Loss Accounts’ for the whole of England and Wales (some counties have few or none) and most of the original documents are at The National Archives (TNA) in the series SP 28. The Tysoe ‘Account’ discussed here (TNA: SP 28/184/4 and /2) is one of nearly 200 for Warwickshire now available on a publicly-accessible database hosted by Warwickshire County Record Office (WCRO) at: https://heritage.warwickshire.gov.uk/civilwaraccounts.

‘Your Petitioner being a poore man and aged….’

The petition of Thomas Tasker, a labourer of Epwell in Oxfordshire, is not, as might be expected, a plea for financial aid for a maimed soldier in the ‘Civil Wars Petitions’ project. Rather surprisingly it is one of two petitions which form part of the ‘Loss Account’ for Tysoe in Warwickshire, a document that evaluates the financial and material losses suffered by local inhabitants through parliamentary activity in their constablery. The two petitions follow the usual pattern of those in the ‘Civil Wars Petitions’ project with an address to the County Committee for Accounts and details of the petitioner’s experience couched in the usual obsequious language and with prayers offered for County Committee members. Tasker’s is signed but neither have the customary signatures of supporters. This blog looks at what the two petitions tell us about civilian suffering in the First Civil War in Warwickshire and why they might have been included in the Tysoe ‘Account’.

The arrival of an army in a locality could have a devastating impact on the lives and livelihood of the civilian inhabitants (image © Jennie Daniels Photography)

As Ann Hughes has shown, the parliamentary Committee of Accounts ordered the compilation of ‘Loss Accounts’ for constableries (usually the same as parishes) throughout the kingdom after the defeat of Charles I and his royalist forces at the battle of Naseby. Their compilation resulted from ‘bitter intra-parliamentarian divisions’ between moderates wanting a peaceful settlement with the King and fearful of ‘military domination and autocratic committees’ as opposed to the ‘energetic war regime’. The ‘Accounts’ were to cover the period from the start of the ‘Long Parliament’ in late 1640 until the end of 1646. They are sometimes called ‘compensation’ accounts although there is no evidence that compensation was ever paid in any systematic way. Compilers, usually constables and ‘chief inhabitants’, were to include all losses of money, plate, horses, arms, household goods, rents, provisions, free quarter (free board and lodging for passing soldiers) and payments of taxes of all sorts. They were also to include the names of the parliamentary officers, soldiers or officials who had received, taken or seized these items. Losses from royalist activity should not have been included but quite often were.

The inclusion of formal petitions for redress in Warwickshire ‘Loss Accounts’ is rare but Tasker’s petition and that of Elizabeth Clarke are part of the ‘Account’ for the constablery of Tysoe in south Warwickshire (TNA: SP 28/184/2). Epwell was in the neighbouring parish of Swalcliffe, just over the Oxfordshire border, and Tasker’s request for payment for the loss of goods and livelihood, along with a complaint of another Epwell man, Walter Medowes, may have been included in the Warwickshire returns by accident, or because both complaints relate to harsh treatment by the commander of a nearby Warwickshire garrison. He was Major George Purefoy, the young governor of the small Compton House garrison in the parish of Compton Wynyates adjacent to Tysoe. Compton had been the ancestral home of the royalist Earls of Northampton but was seized by the parliamentarians in June 1644 and the Tysoe ‘Account’ reveals the extent to which a governor like Purefoy could terrorize the local population. A succession of Tysoe petty constables had the unenviable task of acting on his forty or more warrants. One was addressed to the ‘most base Malignant Counstable and Townes of Tysoes [sic]’, commanding the constable to send a labourer from each household for a week’s compulsory work ‘upon paine of imprisonment and plunderinge’. Shortly after, Purefoy ominously commanded the constable and chief inhabitants ‘to Answere to such thinges as should be laide to their charge’. Four days later he ordered the constable ‘upon paine of Death’ to send forty labourers, four cart-teams and all the available provision to the Compton garrison. Similar ‘blustering Warrants’ (as Mercurius Aulicus put it) confidently signed by Purefoy, were sent to constables in north Oxfordshire also controlled by troops from Compton and Warwick Castle garrisons.

The Tysoe ‘Loss Account’ includes not only the petitions and detailed claims for recompense from individuals but also lists of named inhabitants, men and women, forced to undertake labouring tasks for long periods without pay: digging, pulling down walls, hay-making, breaking ice (presumably a defensive precaution to prevent a royalist attack across the moat in winter) and using horse-teams to carry turf, wood and muck. As David Appleby has pointed out waggoners and their carts were often conscripted from the local population and could suffer the same dangers of injury and death as soldiers. Nicholas Tysoe, constable of Tysoe in 1645, was sent to carry provisions and provender to the guard at nearby Ratley. He also paid for two carts, both lost when they were taken for Sir William Waller’s use. William Callowe sent his team, cart and ‘a man’ to serve at Compton garrison for thirty days at a cost to him of six pounds. In another ‘Loss Account’, for Tanworth-in-Arden Heathside (TNA: SP 28/182/1 f5v), Thomas Disson, a carrier between Tanworth and London, was pressed into service with his wagon for six weeks to carry ammunition from London to Oxfordshire. Even though the better-off Tysoe residents could afford to hire labourers to perform work or fetch and carry for them, Major Purefoy’s demands meant money and time were diverted away from the normal economic activities of farming, craft production and selling goods and produce.

Purefoy’s autocratic governance fell particularly heavily on Thomas Tasker and Walter Medowes. They had, they said, been ‘wrongfully’ and ‘unjustly’ imprisoned. Medowes’ brief account tells of lost clothes, food and household goods but also of being hanged ‘by neck and ristes’ during his three weeks’ imprisonment at Compton House. Tasker’s petition speaks of goods being ‘violently’ taken away in the middle of a December night from him and his wife, both ‘aged’. The Major’s ‘harsh speeches’, unjust treatment and the ‘sudden fright’ of the attack rendered the couple ‘sickly and weake’ and unable to work and suggests trauma from a form of psychological torture.

Ransom and extortion for military expenses compounded the burden of heavy taxation and time away from normal economic activities occasioned by the Civil Wars (photo credit: Maureen Harris)

Arbitrary imprisonment, as experienced by Tasker and Medowes, seems to have been used by Purefoy to subdue the Tysoe inhabitants. Henry Eglington was incarcerated at Compton House, as was William Callowe who was not released until he had provided Purefoy with eight hundredweight of butter and seven hundredweight of cheese. Two Tysoe residents, Robert Rose and William Bratford, who had been former soldiers ‘in the King’s army’ and had returned home to ‘make [their] peace’, were not surprisingly imprisoned by Purefoy until they were ransomed. Raphe Wilcox’s and Henry Middleton’s sons, and Rose Mister’s servant, were seized on their way to the markets at Warwick and Stratford and were taken to Warwick Castle. The governor there, Colonel John Bridges, would not release them, or the goods they were carrying, until a substantial ransom was paid. The opportunity to collect ransom-money, to raise income for military expenses, was probably the chief reason for these men being seized but they may also have been suspected of carrying messages or spying.

Anne Malins’ husband and John Mister were both imprisoned for ransom at Warwick while trying to retrieve horses seized by parliament troops. Mister valued his horse at £8, the price for a superior animal, though this was nothing compared with Thomas Clerke of Wolfhamcote’s valuation of £30 for the seizure of his ‘great Bay horse fower yeres old’ (TNA: SP 28/184/6 f3v). The average value for a horse was £4 to £6, or £2 to £3 for an inferior one. Tysoe man, Edward Boreman, had his good horse taken in exchange for a poor one and claimed a loss of £4. Some stolen animals were found and redeemed for perhaps half the animal’s full value, but many horses died in battles and skirmishes or, if horses were returned or retrieved, they had often been worked so hard that they suffered illness or death. Most of Tysoe’s 114 horses, mares, geldings and colts reportedly taken by parliament soldiers probably died.

The seizure of horses (and sometimes oxen) resulted in the inability of farming communities to function. A Rowington man complained of ‘hyndrance of Tillage’ when all his cattle were taken including, presumably, his plough-team (TNA: SP 28/185 f60v), while the inhabitants of Lillington excused themselves to the Earl of Denbigh, Warwickshire’s parliamentarian commander, who had demanded yet more horses for military use. They were, they said, ‘wonderfully willing’ to comply but heavy quartering, loss of seed-corn taken to feed cavalry horses, and particularly the ‘spoyling some of our horses, & exchanging others’ meant they were unable to accede to his request (WCRO: CR 2017/10/67).

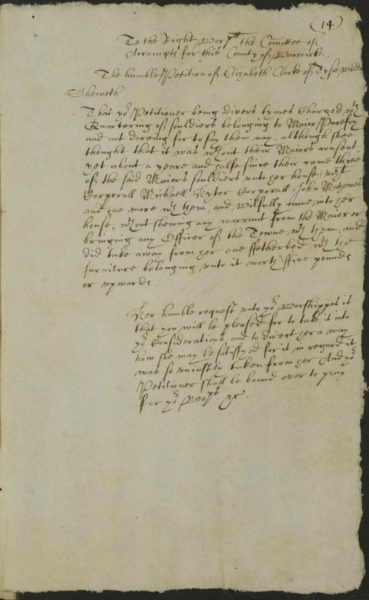

The petition of Elizabeth Clarke (image copyright The National Archives, SP 28/184/2, used with permission)

A second rare ‘humble’ petition in the Tysoe ‘Account’ is from the widowed Elizabeth Clarke and highlights a common complaint in many ‘Accounts’; the burden of providing free food, drink and lodging for passing troops, sometimes in large numbers, and the ‘unjust’ plunder of essential items or prized possessions. Heavy quartering is described in the ‘Loss Account’ for Burmington, a small village near Tysoe with only 28 households. In June 1644, 450 of Waller’s London foot-soldiers were quartered there for two days (TNA: SP 28/182/3). Stockton, a small township of 42 households in east Warwickshire, endured even heavier quartering with ten incidents between 1644 and 1647, often of hundreds of cavalry at a time such as Colonel Hammon’s 800 horse-troops quartered there for two days and nights in July 1644 (TNA: SP 28/183/11). Cavalry horses were frequently left to graze unchecked, eating corn and pulses in the fields, meadow-grass reserved for hay-making or simply trampling growing crops. Mistress Clapham at Willenhall complained that Colonel Vermuyden’s 2000 horses had ‘Eaten up all my grasse, and spoyled my Corne and his men had all my provision in the house to the vallew of £30’ (TNA: SP 28/182/2 f3v).

Widow Clarke’s Tysoe petition seeks redress for frequent and unauthorized quartering by Major Purefoy’s troops and the plundering of a bed and hangings ‘unjustly taken from her’ by three of his soldiers. Her case was not particularly unusual. In the Tysoe ‘Account’ the bill of losses immediately before her petition is from Isabell Meakins, a widow of Tysoe Lodge, who claimed £12 10s for provisioning 500 men and horses of Waller’s and some of his ox-teams in June 1643, stating she had lost some of her tax receipts when her house was plundered. Francis Clarke, a Tysoe gentleman, claimed £300 for loss of horses and most of his household goods and possessions as well as suffering heavy losses in tax, quartering and money. In large garrison towns such as Coventry and Warwick, and in villages near smaller garrisons, troops were quartered on a semi-permanent basis, usually in ordinary civilian homes where their armed presence must have been disturbing, particularly when they were ‘strangers’ from outside the locality. As David Appleby has found, the Scots Covenanter army, which swept through Warwickshire in the summer of 1645, was starved of money and food and plundered ruthlessly. It became deeply unpopular, and many ‘Accounts’ have a separate section for ‘Losses from the Scots’. Even local troops regularly raided homes, smashed windows, stole goods, food and money and threatened the inhabitants. At Rugby in 1644 troop violence was so bad that four ‘abusive fellowes for their ill behaviour’ were punished at Coventry (TNA: SP 28/186/5 f3v).

The reason for Purefoy’s harsh treatment of civilians in the area around Tysoe is not hard to explain. This was royalist country, far from the centres of parliamentarian strength at Coventry, Birmingham and Warwick. Tysoe itself was under three miles from the royalist garrison at Banbury Castle, governed by the young William Compton, brother of the Earl of Northampton, who, like his siblings, was a royalist officer. Purefoy struggled to raise military taxes to support his garrison because some inhabitants, such as those at nearby Butlers Marston, also paid military taxes to ‘his Majesty’s garrison’ at Banbury (TNA: SP 28/183/12). Many south-Warwickshire inhabitants in the area were the Earl’s tenants, and parishes there were dominated by royalist and high-Anglican or Catholic families: the Underhills of Idlicote, the Clarkes of Oxhill and Tysoe, the Sheldons of Long Compton and Whichford and the Bishops of Brailes. It was to this safe royalist area that Archbishop Juxon ‘retired’ from London in the 1640s, celebrating Anglican services in the area unmolested until he resumed his appointments at the Restoration, and there is later evidence from Tysoe of sympathy for, and probably active adherance to, catholicism. For Purefoy, terror and threat were his weapons of choice to counter royalist support amongst a naturally hostile population.

Thomas Tasker’s and Elizabeth Clarke’s claims were made in the form of formal petitions rather than the normal bills of individuals, and this potentially opened up direct channels of communication with the parliamentary County Committee and through them with the central accounts committee in London established in February 1644. As Ann Hughes has shown, this central committee was composed of mainly moderate ‘Presbyterians’, ‘increasingly opposed to military dominance’ and eager for ‘potential evidence for the misdeeds of rival parliamentarians’. The two Tysoe petitions highlighted George Purefoy’s tyrannical rule including imprisonment, threats, torture and illicit quartering and plundering. This was certainly ‘potential evidence’ of ‘misdeeds’. What is perhaps more surprising is that Tysoe’s ‘Account’ is the only one in this south-Warwickshire area to detail such incidents. There are rare references to threat and imprisonment in some of the north Oxfordshire parishes under George Purefoy’s control (TNA: SP 28/43) but in the Warwickshire villages around Tysoe with extant ‘Accounts’ (Oxhill, Idlicote, Brailes, Pillerton Priors and Whichford) although they reported the same heavy parliamentary taxation, burdensome quartering and demands for forced labour there are no references to the tyranny, threat, torture and frequent imprisonment described in Tysoe. There was no obvious reason why the Tysoe inhabitants should have been singled out for particularly harsh treatment so were they unlucky, or particularly brave to submit such detailed claims of injustice? Were they counting on support from the Earl of Northampton, the royalist garrison at Banbury or the King at Oxford to exact revenge? It was more likely that, having been identified by Purefoy as inhabitants of a ‘base Malignant’ place, they had nothing to lose by calling attention to his tyrannical behaviour in anticipation of justice from the central Committee of Accounts, punishment for Purefoy and restitution for their suffering and losses, events that never in fact came to pass.

A view of the parish of Tysoe, Warwickshire (image credit: Maureen Harris)

Maureen Harris researched the relationship between Warwickshire clergy and parishioners between 1660 and 1720 for her PhD from the University of Leicester (2015) and has since published articles and chapters on this theme. She collaborated on the ‘Battle-scarred’ exhibition at the National Civil War Centre and between 2018 and 2020 devised and led a volunteer project to transcribe all the known Warwickshire ‘Loss Accounts’, now available on a publicly-accessible database. She is currently editing them for a Dugdale Society volume.

Further Reading

Ann Hughes: ‘”The Accounts of the Kingdom”: Memory, Community and the English Civil War’, Past and Present, 230: 11 (2016), pp. 311-329.

Ann Hughes: ‘Diligent enquiries and perfect accounts: central initiatives and local agency in the English civil war’, in Chris R. Kyle and Jason Peacey (eds), Connecting Centre and Locality: Political Communication in Early Modern England (Manchester: 2020), pp. 116-132.

Philip Tennant, Edgehill and Beyond: The People’s War in the South Midlands 1642-1645, Banbury Historical Society, 23, (Stroud: 1992).

John Wroughton, An Unhappy Civil War: the Experiences of Ordinary People in Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire, 1642-1646 (Bath: 1999, 2000).