‘The endeavours of your servants’: Oliver Cromwell, Military Welfare and Civil War Petitions

The figure of Oliver Cromwell looms large over the history of the Civil Wars. The working farmer who rose to be head of state, the Captain with no prior military experience who became General of one of England’s most successful armies, the man who provokes reverence in some and revulsion in others: it is seemingly impossible to escape mention of this man when discussing the events of the mid-seventeenth century. So, now in its fifth year, it is finally time for Civil War Petitions to consider, in this blog by Ismini Pells, the relationship of Oliver Cromwell to the military pension scheme and his role in the politics surrounding military welfare during and after the Civil Wars.

Oliver Cromwell (Fairclough Collection, reproduced by permission of the University of Leicester)

A search of the Civil War Petitions website in its current state reveals that Cromwell is known to have provided certificates for the petitions of at least nineteen maimed soldiers and war widows. This is more than any other military commander, parliamentarian or royalist. This is particularly noteworthy considering that the overwhelming majority of material that has survived dates from the royalist period of administering the pension system from 1660 onwards. It might be pointed out that Cromwell was Lord General of the New Model Army (and served for a much longer time period than Thomas Fairfax) and his later political prominence as Lord Protector may have made him a more attractive target to claimants seeking support for their petitions. However, all but seven of the cases on the Civil War Petitions website that Cromwell provided certificates for date from the time before he was installed as Lord Protector. Of the remaining seven, three date to 1654 (i.e. shortly after he was enthroned as Protector). The earliest evidence for certificates issued by Cromwell dates from 1650. No doubt more instances will emerge of Cromwell supporting petitions from maimed soldiers and war widows during the time he was Lord Protector, especially as the Civil War Petitions project publishes the State Papers collections in The National Archives. These collections contain the petitions submitted to central government authorities and thus will include the petitions addressed to Cromwell from claimants seeking pensions funded from central government authorities, over which Cromwell had an influence as Lord Protector. However, as far as the veterans and widows who obtained pensions from the quarter sessions were concerned, the evidence found so far suggests that the number of certificates issued by Cromwell in support of these cases spiked during the period 1651-3.

Sir Thomas Fairfax (Fairclough Collection, reproduced by permission of the University of Leicester)

Philip Skippon (Fairclough Collection, reproduced by permission of the University of Leicester)

Cromwell was hardly unique in his keen sense of the duty of care owed by an officer to his men. In an earlier blog, Andrew Hopper drew attention to support given by Sir Thomas Fairfax to the claims of one maimed soldier and the widow of another soldier who had been known personally to him. Likewise, Philip Skippon, commander of the infantry in the New Model Army, issued a certificate on behalf of the widow of John Francis, who had been killed at Naseby whilst Lieutenant-Colonel of Skippon’s own regiment (TNA, SP 28/265, fol. 308). On the royalist side, Mark Stoyle highlighted the endorsements by Bartholomew Gidley of Winkleigh, a former captain in the king’s forces in the Southwest, on the petitions of several maimed soldiers from Devon in support of their claims. Stoyle concluded that this was ‘striking evidence of the fact that the bonds between some former Royalist officers and their soldiers had continued to endure long after the Civil War was over’. Indeed, the Civil War Petitions website displays further evidence in support of Stoyle’s argument in the twelve certificates issued by James Compton, earl of Northampton, for veterans of his regiment from Northamptonshire who had fought for the king’s cause.

As these cases show, the sense of noblesse oblige was especially keenly felt when the soldier was personally known to the commander. Thus, it is especially interesting that Cromwell seems to have issued numerous certificates on behalf of individuals that he cannot have known personally. For example, on 12 July 1653, the Denbighshire Quarter Sessions which met at Wrexham ordered that upon the certificate of the Lord General dated 15 June 1652 that Aron Hughes was killed in the parliament’s service, a pension of 40 shillings per annum be granted and allowed to Ann Hughes, widow, to maintain herself and children. It was recorded that ‘the said Aron having taken armes in this county & killed at Mountgomery’. The battle of Montgomery, fought on 18 September 1644, was a large-scale battle that resulted in a decisive parliamentarian victory. However, the parliamentarian army on this occasion was led by Sir Thomas Myddleton and Colonel Thomas Mytton, with detachments led by Sir John Meldrum, Sir William Brereton and Sir William Fairfax. Not only was Cromwell not present, but it is highly unlikely that he would have met Aron Hughes if Hughes, as his widow claimed, had enlisted in Myddleton’s native Denbighshire and thus possibly only for the Montgomery campaign.

A similar example is provided by the petition from Christian Markes of South Petherton, widow of Lieutenant Frauncis Markes, to the Somerset Quarter Sessions. Despite providing a certificate for Christian Markes, any personal relationship between Cromwell and the deceased lieutenant seems unlikely. Cromwell did not fight in the earl of Essex’s campaigns in the Southwest in June to September 1644 and, with the exception of a brief sojourn between the battle of Edgehill on 23 October 1642 (to which Cromwell arrived late) and the battle of Turnham Green on 13 November (an abortive stand-off), Cromwell did not fight alongside the earl’s army until the second battle of Newbury on 27 October 1644 – after Frauncis Markes’s death. Nevertheless, Cromwell’s certificate did the trick and the court awarded a gratuity of £4 ‘to Christian Markes recommended by the Generall for reliefe’.

Interestingly, Cromwell provided certificates for war widows in almost equal numbers to those he issued for maimed soldiers: nine of the nineteen claimants Cromwell is known to have supported were widows. There is evidence from the later period when claimants began to seek support from Cromwell as Lord Protector for monetary relief from central government funds to suggest that his support for the widow’s cause was both well-known and well-exploited. Jane Meldrum, widow of Colonel John Meldrum, petitioned Cromwell on 29 March 1655 that she hoped ‘yo[u]r Highnes wil bee gratiously pleased to Number her amongst yo[u]r distressed widows whom God hath drawne forth of yo[u]r pious heart mercifully to relieve, And Christ will put it to yo[u]r Accompt on the Great day’ (TNA, SP 18/95/81, fol. 108). Meldrum aimed directly at Cromwell’s sense of Christian duty in a cunning attempt to provoke him into affirmative action, inferring that Cromwell was known for his willingness to look favourably on distressed war widows.

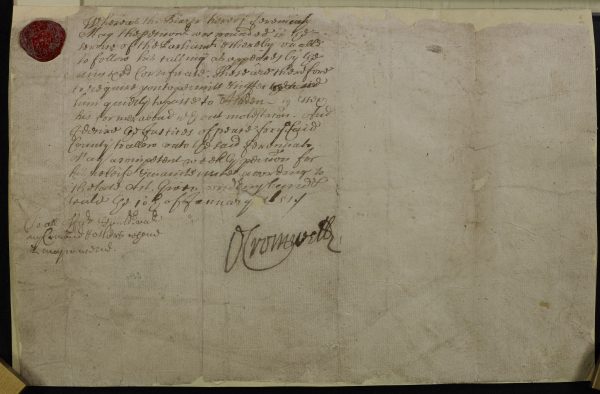

The certificate for Jeremiah Maye from Oliver Cromwell (image reproduced by permission of Essex Record Office under a CC-BY-NC licence).

Of course, it was not just widows who sought certificates from Cromwell to support their pension claims at the quarter sessions and Cromwell’s propensity to assist maimed soldiers in this matter was equally well known. On 2 January 1652, Richard Mabbon, as governor of the Savoy Hospital wrote to William Malin, secretary to Cromwell at the time. Mabbon requested Malin’s help in procuring a certificate from Cromwell for Samuell Miles, Robert Webb and six others maimed soldiers from Essex who intended to seek a pension from the quarter sessions at Chelmsford. As veterans of Worcester, Miles and his comrades had a clear claim to a certificate from Cromwell as the commander-in-chief of the New Model Army at that battle, fought on 3 September 1651. However, news of Cromwell’s willingness to provide certificates for maimed soldiers seems to have travelled fast within the county of Essex and, as was shown in the cases of widows, soldiers with no prior connection to Cromwell sought his support for their pension claims at the quarter sessions. One such soldier was Jeremiah Maye of Ashdon in Essex, who petitioned Cromwell around the beginning of January 1652. Cromwell duly obliged with a certificate on 10 January.

Maye’s petition had plainly stated that the siege of Basing House at which he was wounded was not Cromwell’s devastating storm of 1645 but one of the earlier attempts made on the stronghold by Sir William Waller in either 1643 or 1644 (it is not entirely clear which). Thus, not only was there no military (let alone personal) connection between Maye and Cromwell, but Maye had been injured in an encounter that had happened at least seven or so years previously. Why did Maye approach Cromwell to support his belated claim for a pension and why did he consider the early 1650s to be as suitable time to do this? Indeed, why did Cromwell agree to issue Maye – a soldier with whom he had no connection – with a certificate at this time?

These questions bring us neatly back to the observation made at the start of the article that the evidence gathered by the Civil War Petitions project so far suggests that the number of certificates issued by Cromwell in support of veterans and widows who obtained pensions from the quarter sessions spiked during the period 1651-3. Why was this? Perhaps the answer to these questions lay in the tensions between the army and parliament that followed the battle of Worcester. Following the final defeat of the royalists at Worcester, the Commonwealth was now in a secure position and the leading army officers, including Cromwell, returned to active politics at Westminster. At this time, parliament’s focus shifted from survival to debating the nature of the Commonwealth’s political settlement. Cromwell had signalled his vision for what form this political settlement should take in the oft-quoted passage from a letter written to Speaker Lenthall the day after the battle:

“The dimensions of this mercy are above my thoughts. It is, for aught I know, a crowning mercy. Surely, if it be not, such a one we shall have, if this provoke those that are concerned in it to thankfulness, and the Parliament to do the will of Him who hath His will for it, and for the nation; whose good pleasure it is to establish the nation and the change of the government, by making the people so willing to the defence thereof, and so signally to bless the endeavours of your servants in this late great work. I am bold humbly to beg, that all thoughts may tend to the promoting of His honour who hath wrought so great salvation, and that the fatness of these continued mercies may not occasion pride and wantonness, as formerly the like hath done to a chosen nation; but that the fear of the Lord, even for His mercies, may keep an authority and a people so prospered, and blessed, and witnessed unto, humble and faithful; and that justice and righteousness, mercy and truth may flow from you as a thankful return to our gracious God.”

For Cromwell, the lesson of Worcester was that God had demonstrated his favour towards the army, parliament and the nation. Cromwell thus exhorted parliament to repay God’s favour in order to continue to benefit from it by showing their gratitude towards the ‘servants in this great work’ and adopting the programme of Church and law reform championed by the army. As these hopes failed to materialise over the next twelve months, the army became increasingly disillusioned with parliamentary delay in these matters and began agitating for the dissolution of the Rump. In August 1652, the army made a series of demands concerning the dissolution and calling of a new parliament, along with their requirements for religious reform, law reform, poor reform, and pay and welfare provisions for soldiers and veterans. Military welfare during the early 1650s was thus a matter interconnected with the army’s reform programme during this period. Although Cromwell pleaded for restraint with the army in their actions, he was heavily sympathetic towards their demands. Furthermore, Cromwell was disappointed with the Rump’s treatment of the army more generally, especially the failure to address the deficit in the army’s wage bill and the privileging of MPs’ friends over the army in the plans for the redistribution of Irish land.

Oliver Cromwell at the Battle of Worcester, 17th century painting, artist unknown (image from Wikipedia, reproduced under a Creative Commons licence).

There is thus reason to suggest that Cromwell may have viewed his provision of certificates in support of maimed soldiers and war widows who were seeking pensions at the quarter sessions as a way of demonstrating his support for the army and its political policies at this time. Helping to ensure that those who had suffered for the service to the parliamentary cause received some degree of compensation for their sacrifices was not only an issue that was dear to Cromwell’s heart but an area over which he perhaps had more direct influence than other aspects of the army’s agenda. Issuing certificates for maimed soldiers and war widows did not require anyone else’s consent and was a far more straightforward affair than persuading his more conservative colleagues in parliament to pursue programmes of legal and religious reform which were prone to becoming bogged down in constitutional and spiritual entanglements. Cromwell’s enthusiasm for the army’s reform programme in the aftermath of the battle of Worcester reached its zenith around the time of his forcible dissolution of the Rump Parliament in April 1653 and the calling of Barebones Parliament in July of the same year. Yet within a year, Cromwell’s position had become more cautious – the same time that the stream of certificates issued by Cromwell for maimed soldiers and war widows at the quarter sessions begins to run dry. Time will tell if the hypothesis offered here will stand up to scrutiny with the completion of the Civil War Petitions project. However, at present, the evidence points towards the conclusion that Cromwell’s support for the military pensions distributed at the quarter sessions should not be viewed as an entirely uncontentious issue. Instead, it seems that this should be placed within the broader context of the army and parliament’s competing visions for the future of the nation that followed the end of the period of active fighting during the Civil Wars.

Further Reading

John Morrill, ‘Cromwell, Oliver (1599–1658), lord protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/6765.

Stephen Roberts, ‘The battle of Worcester and the career of Oliver Cromwell’, Cromwelliana (1989), pp. 9-13.

Blair Worden, The Rump Parliament, 1648-1653 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974).