Aristocratic Widowhood and Bereavement: The Household Accounts of Katherine, Lady Brooke

Whilst our project showcases the petitions for welfare penned for the war widows of officers and soldiers, it touches less on the experience of those widowed when aristocratic commanders were killed. Thanks to the survival of the Brooke Household Accounts in the Warwickshire County Record Office, Andrew Hopper shows there is much we can learn about the everyday life of Parliament’s foremost war widow, Katherine, Lady Brooke, after she lost her husband in the spring of 1643.

In contrast to their many royalist counterparts, only two English noblewomen became parliamentarian war widows. The first of these was Arabella, Lady St John, whose husband Oliver St John, fifth baron St John of Bletso, was mortally wounded at Edgehill. The circumstances of Lord St John’s death did not lend themselves to successful parliamentarian propaganda. Arabella was allowed to retreat into a secluded and modest widowhood, hardly in keeping with her status as a peeress of the realm. The second to lose her husband in combat was Katherine, Lady Brooke (c.1618–1676), widow of Robert Greville, 2nd Lord Brooke (1607–1643). The contrast between the experience of widowhood by Katherine and Arabella can hardly have been greater.

Author’s photograph of Lichfield Cathedral.

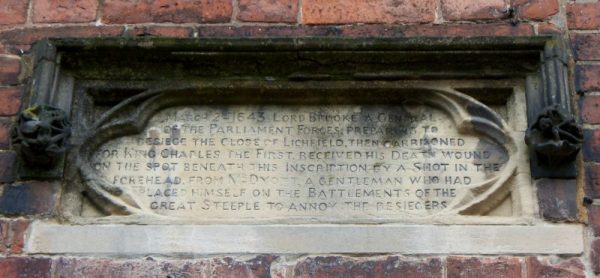

Lord Brooke had been at the forefront of aristocratic opposition to Charles I during the 1630s. He emerged as one of the Long Parliament’s popular war leaders during the opening year of war. On St Chad’s day on 2 March 1643, at the siege of Lichfield Cathedral Close, Brooke was killed at the door of this house on Dam Street. He was shot through the eye from extreme range by a musket fired from the cathedral tower 177 yards away. He was killed instantly and buried around a month later in the vault of his predecessor and cousin, the 1st Lord Brooke in the chapter house of St Mary’s Church, Warwick.

Author’s photograph of Brooke House, Dam Street, Lichfield.

Brooke’s death was a hammer blow to the parliamentarian cause. The royalist historian, Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon later reflected how Brooke’s death ‘was exceedingly lamented by that party, which had scarce a more absolute confidence in any man than in him.’ The suddenness of Brooke’s death left his family and household unprepared and in shock. Brooke’s widow, Katherine, was aged only twenty-four, pregnant with their fifth son, Fulke, and had four other infant sons to look after, all aged under six years. The Long Parliament exalted Brooke as a Godly martyr for their cause and were determined that their treatment of his bereaved widow, herself the daughter of the late Francis Russell, 4th Earl of Bedford, should be seen to be generous and exemplary.

Author’s photograph of the plaque above the door at Brooke House, Lichfield.

Among the many elegies to Lord Brooke, one was personally addressed to Katherine by John Wallis, the cryptographer, and chaplain to another famous godly military widow, Mary, Lady Vere. Wallis’s condolences were particularly fulsome, exhorting that Katherine’s personal grief was owned and shared by the kingdom:

‘We first your Losse, and then your grief bemone;

(Some Ease, in Sadnesse, not to weep Alone:)

Our Teares (ambitious) make their sad addresse;

(We’d bear a part, that You might weep the lesse.)’

(British Library, Thomason, E93(22), John Wallis, On the Sad Losse of the Truly Honourable Robert Lord Brook: An Elegie, to his Vertuous and Noble Lady (London, 1643), frontispiece, sig. 2r.)

Portrait of Katherine Greville, Lady Brooke, by Theodore Russell, 1643 (Warwick Castle).

Katherine came to understand how to play the part of the patient and stoic Godly widow, an image communicated effectively in this portrait of her in mourning attire by Theodore Russell. The painting depicts her holding a posy of flowers that include pink laurel which was to represent honour, triumph and eternal life, along with rosemary to signify remembrance.

Katherine’s numerous petitions to the House of Lords conveyed a similar message. They were carefully crafted to represent Katherine in the most favourable and deserving light, prizing her patient forbearance and suffering in God’s (and Parliament’s) cause, above the pursuit of her personal interests. This was so important because widowhood brought a loss of status and endangered noble patrimonies, especially during a time of civil war.

Katherine received a letter from the King dated 15 April 1644, erroneously addressed to ‘Dame Anne Brooke widdow’, demanding she surrender the custody of her son and heir, Francis, 3rd Lord Brooke, upon pain of a fine of £5,000. To prevent Francis, who was scarcely seven years old, from falling into enemy hands, Katherine petitioned Parliament for his wardship. This was granted in August 1644, despite the King’s attempts to award Francis’s lucrative wardship to his favourite, Lord Digby, who was married to Katherine’s sister.

In January 1648, the House of Lords voted Katherine the sum of £5,000 for the education of Fulke, to be paid for out of the Irish lands of the Duchess of Buckingham and her husband, the Earl of Antrim. This made Katherine the most richly compensated war widow of the English Civil War. Some of this money was loaned out at interest to her brother-in-law, Sir Arthur Hesilrige, who had married Lord Brooke’s sister Dorothy Greville. This enormous sum dwarfed the £2 or £3 per annum pension that a common soldier’s widow could hope to receive. We know that the £5,000 was paid in full and almost within three years because Lady Brooke’s household accounts showing these receipts survive.

While many seventeenth-century historians are very familiar with Lord Brooke, only a handful have consulted the Brooke household accounts. Robert and Katherine’s household accounts are part of the Warwick Castle Collection held in the Warwickshire County Record Office at Warwick. They were first used by Ann Hughes to assess the income and economic status of Lord Brooke for her doctoral thesis during the 1970s and then her monograph, Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, published in 1987. A first edition of these accounts covering the period of the 1640s is currently being prepared for publication with the Camden Society, edited by Stewart Beale, Andrew Hopper and Ann Hughes.

Warwick Castle

The household accounts reveal much about how a Godly noble household mobilized for war, both in Warwickshire and the metropolis. They set out aspects of the functioning of Lady Brooke’s households at Warwick Castle, and her two London mansions. Confusingly, these were both called ‘Brooke House’. Situated in Holborn and Hackney, they were the places where Katherine spent most of her early widowhood during the 1640s. The household accounts include valuable evidence of Lady Brooke’s activities and social circles, including dealings with her kinfolk, peers, friends, chaplains and servants. They furnish rich information on the purchase of books, toys and clothes to divert the orphaned boys, thereby providing a valuable source for elite consumption and material culture. The Greville boys received lessons in arithmetic, French, dancing and archery, and were often sent with their maids to Hackney. Once a little older, they frequented the library at Sion College, equipped with books for sermon notes.

Throughout the 1640s, and into the 1650s, Katherine enjoyed close contacts with leaders of the parliamentarian cause. She was required to maintain her brother, William Russell, 5th Earl of Bedford when he was confined temporarily in Brooke House after he returned from his short-lived defection to the royalists in January 1644. It is likely Katherine attended the execution of her late husband’s old enemy, Archbishop Laud, on Tower Hill, in January 1645. Parliament awarded her Lord Digby’s London residence on Queen Street, which she rented out to Sir Thomas Fairfax, the parliamentarian commander-in-chief, during his time in the capital in 1648 and 1649.

In March 1649, Katherine took her eldest son Francis to witness the trials of the royalist lords, James, 1st Duke of Hamilton, Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland and Arthur, Lord Capel. She later purchased for Francis their scaffold speeches. Later that year she visited the republican politician, Alexander Popham, in his house at Littlecote in Wiltshire. At a time when so many castles were being slighted to make them indefensible, the republican Council of State recommended a grant of £1,000 for the renovation of Warwick Castle. Parliament wanted to continue to be seen to honour Lady Brooke, even after the regicide and the abolition of the House of Lords. Ultimately, Katherine was able to accumulate a sizeable estate in her own right that removed any need for her to remarry.

James Cooke (credit: University of Leicester Fairclough Collection)

The household accounts are also of value to historians of military welfare. They reveal that Lady Brooke made charitable payments to the poor that included other widows and refugees fleeing from Ireland, such as ten shillings for ‘the poor Irish woman that was at Bath’. Two shillings were given to ‘divers poor maimed people by my Lady’s command that were carried in a cart.’ Katherine made substantial payments to James Cooke, the pioneering surgeon at Warwick Castle, who was also pastor of a congregational meeting in the town. After 1643, the accounts concluded each year on 2 March, showing how the household’s lives were still shaped and ordered by civil-war bereavement and the anniversary of Lord Brooke’s untimely death.

Ultimately, the conduct and deportment expected of the widows of parliamentarian commanders, and the ways in which they procured favourable responses from authority reflected their active participation within Parliament’s war effort. They appreciated how their condition and that of their orphaned children reflected upon Parliament’s honour. In turn, Parliament owned them as participants in its cause in a way that was different from the royalists whose focus on passive loyalty to one’s sovereign was less manifestly reciprocal in nature. The widows of Parliament’s commanders proved themselves adept at deploying religious and political language to elicit support. They stressed their families’ sufferings, thereby affirming their own loyalty and activism alongside that of their husbands.

They combined the supplicant’s customary language of humility and dependence with a stoic forbearance that accorded with godly notions of honour, public duty, sacrifice and service. The potency of this self-fashioning is evident in the response it provoked from the enemy. Royalist pamphleteers lamented a threat to the gender order, depicting the wives and widows of parliamentarian commanders as domineering, adulterous and conspiratorial, a set of hypocritical puritans on the make, who were worryingly unnatural and unwomanly in their political assertiveness.

Further Reading

Stewart Beale, Andrew Hopper and Ann Hughes (eds), The Household Accounts of Robert and Katherine Greville, Lord and Lady Brooke of Warwick, 1640–1649 (Camden Society, forthcoming).

Andrew Hopper, ‘ “To condole with me on the Commonwealth’s loss”: the widows and orphans of Parliament’s military commanders’, in David J. Appleby and Andrew Hopper (eds), Battle-Scarred: Mortality, Medical Care and Military Welfare in the British Civil Wars (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), pp. 192–210.

Ann Hughes, Gender and the English Revolution (Abingdon: Routledge, 2012).

Ann Hughes, Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).