HIGHLY COMMENDED IN THE BRITISH RECORDS ASSOCIATION’S JANETTE HARLEY PRIZE 2020:

https://www.britishrecordsassociation.org.uk/press-release-winner-of-the-2020-janette-harley-prize-announced/

‘And they called for their pints of beer and bottles of sherry…’: veterans and war widows as brewers and alehouse-keepers.

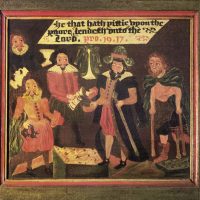

Beer was a staple drink for men, women and even children in early modern Europe, as it was far less likely to be contaminated than water. In our latest blog, David Appleby uses cases from the Civil War Petitions database to show how and why many impoverished military veterans, maimed soldiers and war widows brewed beer and ran alehouses, and how they fared at the hands of the county benches before and after the Restoration. No Interregnum regime sought to impose a complete prohibition on the production and consumption of alcohol, not least because beer was safer to drink than water. Sobriety featured prominently in the Puritan agenda of the 1650s known as the ‘reformation of manners’, but Puritans were not alone in detesting drunkenness and carousing. Neither were Cromwell’s major-generals the first officials to crack down on unlicenced or disorderly alehouses: Assize judges had already conducted two energetic campaigns to close unlicenced establishments and reduce the number of licenced ones during the period of Charles I’s personal rule, in 1630-1 and 1637. The various statutes and proclamations issued in the decades before the Civil Wars had caused considerable confusion as to who had oversight of alehouses, inns, and taverns, and a blurring of distinctions between these various establishments. Inns provided accommodation and victuals as well as drink, but increasingly alehouses were also expected to provide at least some accommodation in order to qualify for a licence. James I had attempted to increase Crown revenue by first franchising the right to license inns, and then alehouses. The disputes and tensions which subsequently arose in Charles I’s reign between these national franchises, Assize judges, county justices, manor courts and parish officers resulted in huge variations in the policing of alehouses, and erratic responses to the crackdowns periodically ordered by higher authority. Attitudes to alehouses were ambivalent. Since Tudor times they had been ‘regarded by many in authority as a leading cause of poverty – places where working people frittered away their earnings on drink and gambling’ [Briggs et al (1996), 48]. There is no doubt that many alehouses were hives of disorder, prostitution, crime, and even sedition. Ever since Edward VI’s reign, those seeking a licence to run an alehouse had been required to deposit the sizeable sum of £10, with two supporters advancing an extra £5 each, as surety for keeping good order in and around their premises. Some county benches demanded even larger sums [King (1980), 41-2]. At the same time, it was widely recognised that the production and consumption of beer and ale were vital to the health of the local economy; an important consideration for communities struggling to recover from the Civil Wars. Fines levied on disorderly alehouses went towards poor relief; and many individuals who might otherwise have been a burden on the parish were able to subsist by keeping an alehouse. Inevitably, a large proportion of these people were too poor to afford the £10 surety and so operated without a licence. Many other poor people scratched out a living by illegally brewing in their homes to supply neighbours and local establishments. By contrast, maltsters tended to be relatively well off, as malting required significantly more capital than brewing or alehouse keeping (not least for the bulk purchase of grain), but their industry still provided gainful employment for the local poor. Maimed soldiers and war widows were among the poorest members of local society. The vast majority of those awarded pensions barely received enough to subsist, and those denied pensions endured an even bleaker existence. As discussed in an earlier blog, many other veterans and widows attempted to shift for themselves rather than apply for charity. Examples in the Civil War Petitions database include John Hall, who petitioned to be allowed to work as a cobbler in Leicester, despite having lost the use of his right hand. Given that brewing and alehouse-keeping involved less physical exertion than many other occupations, it is unsurprising that some veterans and war widows should have chosen to supplement their meagre income in this way. Some veterans petitioned for alehouse licences rather than pensions. William Parker of Beaulieu requested an alehouse licence from Hampshire justices in 1655, citing the wounds he had received in Parliament’s service. In May that same year, the parishioners of West Rudham in Norfolk stressed that Thomas Holman had been so badly afflicted by his military service that he was ‘very unable to work as other poor men to get his living’. They asked that Holman therefore be permitted to ‘draw beer as he has formerly done there five or six years.’ Robert Hansen informed the Lancashire bench in 1656 that he had lost his original livelihood during the four years he had served the Commonwealth in Scotland. He pleaded that ‘having a wife and child to maintain and nothing wherewith to maintain our livelihood withal, I humbly desire your licence to sell ale or beer in Rochdale’. The following year Alice Tarbock, a war widow, also petitioned the Lancashire bench, suggesting that if the justices chose not to give her a pension, they might at least grant her a licence to brew or sell ale in Ditton. Either outcome would allow her to support her three children, for ‘otherwise’, Alice warned, ‘she must be forced to put them upon the parish’. For whatever reason – very possibly because they had been particularly assiduous in closing alehouses during the 1650s – the Lancashire justices took a third course, ordering the churchwardens and overseers of the poor for the parish of Preston to make suitable provision for the Tarbock family. The vague wording of the various Ordinances and Acts concerning maimed soldiers and widows left justices considerable discretion in allowing pensioners to supplement their pension with paid employment. Many magistrates appear to have disapproved of the practice. On receiving reports from informers in 1652 that some of their pensioners had jobs on the side, the Staffordshire bench declared that individuals healthy enough to work were taking money from more needy and deserving cases [Staffordshire Record Office, Q/SO/5, fols. 417, 463]. When Gloucester’s Midsummer Quarter Sessions convened in 1657, justices proposed to raise Samuell Pitt’s pension from £3 to £4 per annum but stipulated that the veteran was ‘not to receive any payment until he has stopped selling ale and beer’. The same attitude was evident after the Restoration: Northamptonshire officials investigating Thomas Roodey’s application for a pension in 1668 concluded that the royalist veteran was a fit candidate for financial relief, ‘except his keeping an alehouse’. However, the officials were satisfied that ‘he will lay aside that calling rather than lose his pension.’ A constant refrain running through all the licensing laws was that persons applying for alehouse licences should be well disposed to the State, and morally fit to run a drinking establishment. After 1649, with licensing powers bestowed unambiguously on county justices, such attributes were even more important to a Commonwealth regime obsessed with the related evils of drunkenness, disorder, and sedition. Consequently, it is interesting to see military service offered as evidence of good character, particularly during the rule of Cromwell’s major-generals. Thomas Crocker of St James, Somerset, was even more explicit than William Parker and Robert Hansen in presenting himself as ‘ever faithful and serviceable unto the State’. Crocker declared that his wounds had left him ‘totally maimed and consequently forever disenabled to get maintenance for himself, his wife and three children.’ The parliamentarian veteran explained that because ‘he could not labour and had no other way to get maintenance, he formerly used to sell beer in his dwelling house.’ Nevertheless, although pointing out that he had not hitherto been prosecuted for any disorder in all the time he had run his unofficial establishment, ‘your petitioner (as he understands) is now indicted for the same, whereby he is likely to be undone unless your Worships be now pleased to extend the eye of pity and compassion towards him.’ Frustratingly, there is no record to indicate how the Somerset bench responded to Crocker’s petition. Sometimes it only required one accuser to prevent the renewal of a licence. Lieutenant Henry Fielding had died during the First Civil War, leaving his wife Grace Fielden (or Fielding) with very little means to sustain their large family. Consequently, for her ‘better livelihood and subsistence’, Grace had subsequently kept an alehouse with the blessing of her neighbours (her petition was endorsed by no less than 24 parishioners). This harmonious state of affairs continued until 1658/9, when one individual ‘did lay such foul aspersions upon me, especially at the last Privy Sessions held for the division of Blackburn hundred, so as by no means I could procure [a] licence to keep ale as formerly I had’. Grace’s obvious indignation at these ‘foul aspersions’ suggests that her detractor may have accused her of running a brothel (many alehouses were closed for allowing prostitution on the premises). She presented herself before the Lancashire bench in 1659 to clear her ‘good name and fame’. Significantly, in her effort to regain her reputation and be considered a fit and proper licensee Grace laid great stress on her status as a war widow, and the fact that some of her sons were now soldiers in Parliament’s service. The question of allegiance figures prominently in the respective cases of Thomas Holte and Mary Allin, but for very different reasons. Thomas Holte of Liversedge in the West Riding of Yorkshire had plainly served as a parliamentarian soldier, as he was granted a pension in July 1646. He appears to have been given considerable latitude to supplement his income, for he is described as a butcher and alehouse keeper in a later document in 1648. However, this document also records that on 13 July 1647 he had called for a health to be drunk to the confusion of Parliament ‘and all that took their part’, and had threatened to kill a customer, calling him ‘Roundhead Reyner’. West Riding justices stripped Holte of his pension and his alehouse licence. Curiously, he is once again recorded as a pensioner after the Restoration, despite the fact that the 1662 Act specifically precluded those who had been in arms against Charles I or his son. Holte’s case contrasts with that of Mary Allin, a widow from Pilton, Northamptonshire, who had completely the opposite experience after the Restoration when her brewing licence was revoked by the county bench in 1667. The certificate submitted by her supportive neighbours (including Pilton’s overseer of the poor, the petty constable, and a churchwarden) laid great stress on the fact that her husband had served as a surgeon in the royalist army, and that the loss of the veteran’s pension following his death had left the Allin family in poverty. Intriguingly, the certificate also inadvertently disclosed that the couple had been allowed to brew beer and run a licenced victualling house throughout the Interregnum, despite the husband’s royalist background. This was almost certainly because they had ‘always carried and demeaned themselves civilly, orderly and handsomely towards all people, and have done much good to diverse lame and distressed people by their very good skill in surgery.’ Like Grace Fielden, Mary Allin had been accused by a disgruntled individual. Her neighbours described the allegations as ‘utterly false and untrue and maliciously done’. The loss of the alehouse licence had been ‘to the great hinderance and amazement of the poor widow and her great family of small children, they not imagining any cause wherefore.’ Again, despite the fact that Mary Allin’s case was considered at the Epiphany Sessions of 1667/8 and again at the Easter Sessions of 1668, there is no indication as to whether Northamptonshire justices restored her licence. This blog shows yet again how the huge collection of records held in the Civil War Petitions database has the potential to shed light on a wide range of societal and political issues beyond military welfare and war relief. Inevitably, the blog must end with many questions: for example, how many other maimed soldiers, veterans and war widows brewed beer illegally or kept unlicenced alehouses, but managed to avoid official scrutiny? Did county benches turn a blind eye to such activities in order to mitigate the burden of war relief in the localities? If so, were Restoration benches more tolerant than those which functioned during the Interregnum? Hopefully, someone reading this blog will be enthused to delve further into the archives in search of answers. Further Reading John Briggs, Christopher Harrison, Angus McInnes and David Vincent, Crime and Punishment in England: An Introductory History (London, 1996). Mark Hailwood, Alehouses and Good Fellowship in Early Modern England (Woodbridge, 2014). Judith Hunter, ‘English inns, taverns, alehouses and brandy shops: the legislative framework, 1495-1797’, in Beat A. Kümin and B. Ann Tlusty (eds), The World of the Tavern: Public Houses in Early Modern Europe (Aldershot, 2002), pp. 65-82. W. J. King, ‘Regulation of alehouses in Stuart Lancashire: an example of discretionary administration of the law’, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire, 129 (1980 for 1979), pp. 31-46. Stephen K. Roberts, ‘Alehouses, brewing and government under the early Stuarts’, Southern History, 2 (1980), pp. 45-71. Keith Wrightson, ‘Alehouses, order and reformation in rural England, 1590-1660’, in E. Yeo and S. Yeo (eds), Popular Culture and Class Conflict, 1590-1914: Explorations in the History of Labour and Leisure (Brighton: 1981), pp. 1-27.

Read More

The War Wounds of Sir Thomas Fairfax

Looking back on his military service during the Civil Wars, Thomas 3rd Lord Fairfax penned his Short Memorials during the 1660s. The manuscript originals survive among the Fairfax Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library. Many years after his death, they were edited and published in defence of his reputation by his cousin Brian. Together with evidence from wartime newsbooks and pamphlets, they provide significant detail about the wounds that Fairfax and many of his close comrades received during their wartime service in the northern campaigns of 1642–45. In this blog, Andrew Hopper chronicles Fairfax’s many wounds, ailments and narrow escapes, suggesting something of their political and cultural significance. Thanks to the kindness of Tom Fairfax, cousin of Nicholas, the current Lord Fairfax, the National Civil War Centre are able to display the wheelchair of the parliamentarian commander-in-chief as one of their star exhibits. Of a striking size and formidable in appearance, it was the showpiece of the Centre’s ‘Battle-Scarred’ exhibition in 2016–2019. It serves as a very physical reminder that civil-war commanders were expected to lead from the front and expose themselves to danger in order to inspire their troops. During the 1660s, despite being scarcely fifty, Fairfax resorted to this wheelchair because of ill-health and the many war wounds that he carried with him. In his Short Memorials, Fairfax was meticulous in acknowledging the hand of God’s providence in explaining his unlikely survival of so many military engagements. His good fortune is magnified when it is considered the dangers he faced and how many times he was wounded. On top of this, Fairfax was quite a sickly man. The fevers he endured during his brief military education in the Low Countries in 1629 frequently recurred, including soon after his marriage to Anne Vere in 1637. Fearing another recurrence of his son’s ill health, Ferdinando, 2nd Lord Fairfax, withheld permission for him to serve against the Irish rebels, despite Sir Thomas’s pleading that the ‘miserable condition our neighbours of Ireland are in doth much affect me’ (Bodleian MS Fairfax 32, fo. 43). On 4 January 1642, Sir Thomas’s mother-in-law, Mary, Lady Vere, congratulated Ferdinando on the wisdom of this decision: ‘I think you did exceeding well to stay him from Ireland. He owes himself more here, if there should be occasion: & this winter is a most extreme cold one: he is to me as my own’ (Bodleian MS Fairfax 32, fo. 19). Once hostilities commenced, it did not take long for Fairfax to receive his first wound. The London press reported him wounded in the head in only his second engagement, defending his quarters at Wetherby from a surprise attack by horse and dragoons under Sir Thomas Glemham on 25 November 1642 (BL, Thomason E.128[28], Speciall Passages, no. 16, 22–29 November 1642, pp. 135–6). Caught unawares and not fully dressed, Fairfax recalled that he led his court of guard consisting of 2 sergeants and 2 pikemen to fight off a charge by Sir Thomas Glemham and 6 or 7 of his officers. The royalist Sir Henry Slingsby recorded ‘every one had his shot at him, he only making out at them with his sword’. If their aim had been better, Fairfax’s military career would have been over before it had scarcely begun. These 4 foot soldiers had likely saved his life, for as Slingsby pointed out, Fairfax was driven back ‘under the guard of his pikes’ (Daniel Parsons, ed., The Diary of Sir Henry Slingsby of Scriven, 1836, p. 83). An insertion in the margin by his cousin, Brian Fairfax, remarked that one of these soldiers ‘had a pension for his life till 1670’ (Short Memorials, 1699, p. 6). If this pension had been granted by the West Riding quarter sessions, it would have been illegal during the 1660s and the recipient would have risked imprisonment by collecting it. This raises the intriguing possibility that if the pension was paid after 1660, it might have been done so privately, in gratitude by Fairfax himself. The royalists only withdrew from Wetherby when another of Fairfax’s soldiers accidentally dropped a match into a barrel of gunpowder, causing them to believe (wrongly), that the parliamentarians had deployed artillery (Bodleian MS Fairfax 36, fo. 5). On 13 December 1642, Fairfax had another lucky escape when his horse collapsed, having been shot under him during a cavalry raid on royalist quarters at Sherburn-in-Elmet (Bodleian MS Fairfax 36, fo. 6; BL, Thomason E.83[15], A True Relation of the Fight at Sherburn in the County of Yorke, 16 December 1642, pp. 1–2). On 30 March 1643, Fairfax was fortunate again to escape into Leeds after his defeat on Seacroft Moor by Sir George Goring, during which Fairfax’s cornet was captured and the autobiographer, John Hodgson, then an ensign was also wounded, presumably defending his colours. Two months later, during his successful assault on Wakefield on 20 May, Fairfax was again almost captured when he became temporarily separated from his men riding through the streets. Fairfax received his second wound on 2 July 1643 during a sharp cavalry engagement in Selby market place, whilst protecting his father’s army’s retreat from Leeds to Hull. He later recalled: ‘I received a shot in the wrist of my arm, which made the bridle fall out of my hand, which being among the nerves and veins, suddenly let out such a quantity of blood, that I was ready to fall from my horse.’ He seized the reins with his sword hand and got clear of the melee, which allowed his soldiers to lay him down on the ground ‘almost senseless’ until ‘my surgeon came seasonably & bound up my wound, & so stopped the bleeding’. After only a quarter of an hour’s rest, he mounted up, and remained in the saddle for another 20 hours until he arrived in Hull ‘having lost all even to my shirt, for, my clothes were made unfit to wear with rends & blood which was upon them’ (Bodleian MS Fairfax 36, fos. 9–10). If he had been wearing a steel bridle-arm to protect his rein hand, as was customary for civil-war cavalry, this might have carried further metal into the wound. A bridle-arm from the Fairfax collection survives on display in the National Civil War Centre, again on loan thanks to the kindness of Tom Fairfax, which suggests that the wound healed well enough not to inhibit him from wearing this armour during future engagements. His third wound came a year later, ‘a cutt in my cheeke’, during his first cavalry charge at Marston Moor on 2 July 1644. The royalist polemicist, John Crouch later jibed that Fairfax was by this wound ‘marked for a rogue’, intending to undermine his gentility by comparing him to plebeian felons whose faces could be judicially maimed (BL, Thomason E.560[9], A Tragi-Comedy, called New-market-fayre, 1649, p. 5). Many of Fairfax’s cavalry officers were killed early in the battle by royalist musketry. Fairfax’s Short Memorials reflected: ‘The captain of my own troop was shot in the arm. My cornet had both his hands cut [likely defending the colours], that rendered him ever after unserviceable. Captain Micklethwaite, an honest, stout man was slain and scarce any officer which was in this charge, which did not receive a hurt. Major Fairfax, who was major to [John Lambert] had at least 30 wounds whereof he died after he was abroad again and good hopes of his recovery.’ But even more saddening than Major Fairfax’s short-lived revival was the loss of Sir Thomas’s younger brother, Colonel Charles Fairfax ‘who, being deserted by his men, was sore wounded, of which in 3 or 4 days he died.’ Fairfax acknowledged God’s goodness to him that he himself had come away comparatively unscathed, despite being unhorsed, struck to the ground, and again separated from his men. Once again, his horse had been shot from under him (Bodleian MS Fairfax 36, fo. 13; BL, Thomason, E.2[14], A More Exact Relation of the Late Battell neer York, 17 July, 1644, p. 7). The following month, Fairfax received his fourth and most dangerous wound while directing the besiegers of Helmsley Castle. At considerable range, Fairfax ‘received a dangerous shot in my shoulder and was brought back to York’, leaving ‘all, for some time being doubtful of my recovery’. This required 3 months to convalesce and may possibly have deterred him from wearing a back and breast plate thereafter (Bodleian MS Fairfax 36, fo. 13; BL Thomason E.254[28], Perfect Occurrences of Parliament, no. 4, 30 August–6 September 1644, sig. D2r). As Thomas lay recovering, his cousin Sir William Fairfax was mortally wounded in the Battle of Montgomery on 18 September 1644. One newsbook claimed that by refusing to treat, he was wounded 12 or 13 times. He died 16 hours later, his last words a request for Sir William Brereton to look after his widow and children (BL Thomason, E.10[7], The Kingdom’s Weekly Intelligencer, no. 73, 17–24 September 1644, p. 588–9; BL Thomason, E.10[6], The Weekly Account, no. 56, 18–24 September 1644, p. 448; BL Thomason, E.10[5], The London Post, no. 5, 24 September 1644, p. 8). Despite having just lost his son second son at Marston Moor and with his eldest son lying dangerously wounded, Ferdinando greeted the news of the ‘mortal wounds of my dear nephew’ with Godly stoicism: ‘blessed be God, the victory obtained over our enemies doth abate my sorrow for any particular friends’ (TNA, State Papers 16/503, fos. 260–1). No sooner had Sir Thomas recovered, he was directing operations at the siege of Pontefract Castle in January 1645. There, he ‘was lately in great danger of being shot by a cannon bullet from the castle, which came between him and Colonel Forbes; the waft of it felled Sir Thomas to the ground, and spoiled one side of the Colonel’s face and eyes’. Forbes survived this terrible injury and was nicknamed ‘Blowface’ thereafter (BL, Thomason E.24[23], Mercurius Civicus, 9–16 January, 1645, p. 790). After he travelled southward to assume command of the New Model Army, Fairfax continued to place himself in the forefront of the fighting. He was fortunate at Naseby, where he ‘received not the least wound; though he engaged bareheaded’ (BL, Thomason, E.288[38], A More Particular and Exact Relation of the Victory obtained by the Parliaments Forces under the Command of Sir Thomas Fairfax, 19 June, 1645, p. 2). However the wounds that he sustained in the northern campaigns continued to trouble him, reminding us that the ‘recovery’ of maimed soldiers from their wounds was rarely total. He wrote to his father from Chard on 8 October 1645: ‘I am exceedingly troubled with rheumatism and a benumbing coldness in my head, legs and arms, especially on that side I had my hurts. It hath pleased the Lord to help me through much extremities, and I trust He will lay no more on me than He will enable me to bear.’ Fairfax was indeed conscious that God had protected him through many dangers: ‘The mercies I have received ought to stop all complaints in His service’ (Bell, Fairfax Correspondence, vol. 1, p. 251). By 1646 Fairfax had developed a kidney stone. Like many soldiers sent there from London’s military hospitals, in August 1646 Fairfax took the waters at Bath to try to ease his condition. He visited again in July 1659 (BL, Additional MS 10114, fo. 49; BL, Additional MS 71448 fos. 48, 50). He enjoyed another narrow escape at the Battle of Torrington on 16 February 1646, when he acknowledged to his father ‘God’s great mercy to me’ after 80 barrels of powder blew up inside a church showering down ‘great webs of lead’ which ‘fell thickest’ onto the ground around him, killing one of his lifeguard’s horses (Bell ed., Fairfax Correspondence, vol. 1, p. 285). During the political entanglements that followed the First Civil War, Fairfax was often accused by his Army’s enemies at Westminster of pretending to be sick at convenient moments. In April 1647, in the midst of his army’s protests over pay and indemnity, he sought medical treatment in London. That autumn, illness prevented him from chairing most of the Putney Debates, until towards their end on 5 November 1647. His chaplain, Joshua Sprigge remarked that Fairfax continued to suffer ‘some infirmities contracted by former wounds’ (Anglia Rediviva, 1647, p. 42), but these seemed not to trouble him during battle. On 1 June 1648, enduring great pain from gout, Fairfax led his soldiers in a furious assault on Maidstone. He was ill again during Pride’s Purge in December 1648, and unable to meet MPs imprisoned by his Army. On top of his illnesses and recurring pain from his wounds, it is likely that from 1649 Fairfax was also troubled with bouts of depression and melancholy over his failure to prevent the King’s execution. The accounts of Fairfax’s army headquarters from December 1646 show him dispensing generous gratuities to maimed soldiers, war widows and refugees from Ireland, some of whom importuned repeatedly for relief. (Ethel Kitson and E. Kitson Clark, ‘Some civil war accounts’, in Miscellanea, Thoresby Society, 11, 1904, pp. 137–235). Perhaps Fairfax was able to empathise in these cases because of his own wounds and bereavements. He considered wounds in service to a cause conferred honour on their bearers and were markers of God’s favour. This could be turned to political purposes. Fairfax commanded widespread respect among parliamentarians, not just because of his military successes, but because his sacrifices in the cause were so physically obvious. In the Protectorate Parliament on 3 February 1659, Sir Arthur Hesilrige proclaimed that the New Model was ‘the best army that ever was in the world’ and used the physical example of Fairfax’s wounds to remind MPs to take good care of it: ‘This noble Lord that sits by me, Lord Fairfax; I bless God that he, having received so many wounds, now sits by my right hand’ (J.T. Rutt, ed., The Diary of Thomas Burton, Esq., London, 1828, vol. 3, p. 56). In December 1659, Fairfax led an uprising in favour of General Monck that seized York, but his kidney stones and gout now forced him to direct proceedings from his coach rather than on horseback. All considered, it is little wonder that Fairfax was resorting to this wheelchair during his final years. His cousin Brian remembered him sitting in it ‘like an old Roman, his manly countenance striking awe and reverence into all that beheld him’ (BL, Egerton MS 2,146 fo. 38). The National Civil War Centre would like once again to thank the Fairfax family for having loaned the wheelchair (along with other important artefacts owned by the general), so that it can be kept for public view as a reminder of the terrible costs of war to the human body. It also bears witness to the extraordinary story of Fairfax’s ultimate survival through so many dangers in this harrowing conflict. Increasingly confined to it, he spent his final years reading, writing and making notes from sermons. He died, aged just 59, of a fever in his home at Nun Appleton, 9 miles southwest of York, on 11 November 1671. During the last morning of his life he called for his Bible. As his eyes grew dim he recited the forty-second psalm (BL Egerton MS 2146, fo. 38), which includes the penultimate verse: 'As with a sword in my bones, mine enemies reproach mee: while they say dayly unto me, where is thy God?' (Authorised Version, 1611). Fairfax's will directed his burial be conducted ‘in such a manner as may be convenient and decent rather than pompous’. It also directed that John Denonley and his wife Elizabeth enjoy their farm rent-free for life, on account of John ‘having received a maim in my service disabling him to earn his living’ (Markham, A Life of the Great Lord Fairfax, p. 445). Further Reading Andrew Hopper and Philip Major (eds), England’s Fortress: New Perspectives on Thomas, 3rd Lord Fairfax (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014). Andrew Hopper, ‘Black Tom’: Sir Thomas Fairfax and the English Revolution (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007). John Wilson, Fairfax: A Life of Thomas, Lord Fairfax, Captain-General of all the Parliament’s forces in the English Civil War, Creator and Commander of the New Model Army (New York, 1985). Mildred Ann Gibb, The Lord General: A Life of Thomas Fairfax (London, 1938). Clements R. Markham, A Life of the Great Lord Fairfax (London, 1870). Robert Bell (ed.), The Fairfax Correspondence: Memorials of the Civil War, 2 vols (London, 1849). Brian Fairfax (ed.), Short Memorials of Thomas Lord Fairfax (London, 1699).

Read More

They also served

The Civil War Petitions project team frequently agonises over whether to include or reject individuals (or their relations) who were involved in the conflict but not technically soldiers. This is rather redolent of the conundrum faced by Winston Churchill’s government in 1944, when deciding whether or not civilians and home-based service personnel should be awarded the 1939-43 Campaign Star (later designated the 1939-45 Star). David Appleby shows in this blog that soldiers were certainly not the only ones killed or wounded during the Wars in the Three Kingdoms. Most of the individuals named below have not made it into our database for one reason or another, but they are at least commemorated in this blog. As Eduard Wagner wrote in European Weapons and Warfare, ‘provisions, ammunition and other military supplies were indispensable to any army’. A large army could have as many as 200 supply wagons, stretching for several miles along the road. Care had to be taken in seeking out the best routes for the wagon train, and protecting it from the enemy. It was vital to have a competent wagon-master-general, as well as drivers, smiths, carpenters and wheelwrights. Wagner gives the impression that drivers were hired during the European wars, but documents unearthed by our project team show that waggoneers were very often conscripted, and their wagons and teams summarily requisitioned. John Griffythes was impressed in Pattingham, Staffordshire, to serve as a driver during the Bishops’ Wars. Sometime during the campaign, he was kicked by a cavalry trooper’s horse, and had to be invalided home. Surgeons pronounced Griffythes’ shattered leg to be incurable, and being unfit for work he became dependent on parish charity. Pattingham’s leading parishioners helped him petition the county Justices in April 1642. The parishioners optimistically claimed that he was a maimed soldier, despite the fact that he was clearly a non-combatant. The Justices generously agreed to treat him as such, ordering an immediate gratuity of £5, and a county pension as soon as there was a vacancy in the pensioner list. Pattingham submitted a further petition to the Epiphany Sessions in January 1643, complaining that Griffythes had not yet received his promised gratuity, much less a pension. The Bench agreed that the ‘the poor man’ should be paid his arrears, plus an extra £3 for the year to come. However, a year later Griffythes petitioned to complain that he had still not received any money. This time the Justices pleaded poverty: Staffordshire’s economy was now being ravaged by the First Civil War, and the county’s Treasurers for Maimed Soldiers had ‘no more moneys in their receipts than to pay the pensions that are already being paid.’ There is no evidence that Griffythes was ever paid. [Staffordshire Record Office, Q/SR/250, fol. 11; /254, fols. 19r, 19v, 20r-23, 21; Q/SO/5, fols. 95, 117, 146, 147.] Whereas John Griffythes was variously described as a servant and a tenant farmer, George Rolfe of Leyton, Essex (who featured in an earlier blog) ran a business as a carrier. In 1643, Rolfe’s wagon and horses were requisitioned for the Earl of Essex’s supply train, as the parliamentarian general made preparations to relieve Gloucester. Rolfe’s team was used to carry ammunition, with all the dangers that entailed. The fact that the wagon was broken and the horses killed at the first battle of Newbury suggests that they were lost in an explosion [Essex Record Office, Q/SO1, fols. 163, 168]. An engineer’s job similarly included handling hazardous materials. During many civil-war sieges they were called upon to construct explosive devices such as ‘pagans’ and ‘petards’, placing the latter against the walls and gates of enemy strongholds. On the other side of those walls, engineers had designed formidable fortifications, even for small garrisons, incorporating all the deadly innovations of the early modern Military Revolution. Experienced military engineers were therefore worth their weight in gold, both in an offensive and defensive capacity. John Hooper, Colonel Hutchinson’s chief engineer at Nottingham (who appears in our database as a signatory to several payments to Nottinghamshire war widows), was described by Lucy Hutchinson as ‘an ingenious fellow’. The case of Leonard Crast shows that engineers ran the same risks as regular soldiers during sieges. In April 1645 Crast petitioned the Hertfordshire parliamentary county committee for money to fund his return to London, on the grounds that he been wounded in the head in Parliament’s service [TNA SP28/232, fol. 720]. Sir John Gell and the Derbyshire parliamentary county committee certainly considered that their engineer, Edward Lions, should be treated like a soldier, as in August 1645 they agreed to pay him thereafter as if he were ‘a gentleman of the pike’ [TNA SP28/226, fols. 195, 217]. Lions had almost certainly supervised Gell’s assault pioneers as they dug trenches and mines under the foundations of Wingfield Manor during the parliamentarian siege of the place in August 1644. In the course of these excavations at least one of the conscripted pioneers – Anthony Hoades of Wirksworth – was ‘unhappily shot to death’ by the royalist defenders. However, it would be another three years before the Derbyshire committee awarded his widow a gratuity of £2, pending consideration of her claim for a war widow’s pension [TNA SP28/226, fols. 244, 500]. The petition of Henry Colier of Allestree, Derbyshire, shows that even duties behind the lines entailed a certain amount of hazard. Colier was a saltpetreman, who collected and processed the saltpetre in order to help supply the parliamentarian garrison of Stafford with gunpowder. Years later, in 1652, Colier claimed that the ‘great and hot labour’ involved in the process had caused his foot to become so badly infected that he had lost his leg, leaving him unable to provide for his wife and three children. The Civil War Petitions database contains details of many surgeons and physicians who worked to cure maimed soldiers during the conflict. The rules of war considered the persons of medical practitioners to be inviolate, as they habitually treated the wounded of both sides regardless of their own affiliation. We do not as yet have any conclusive evidence that any were wounded in combat, although it is noteworthy that William Edwards of Wrexham submitted a certificate to accompany his petition, just as a maimed soldier would. Pensions were certainly awarded to surgeons such as Peter Wray from Lewes, who had served in a parliamentarian regiment; and, after the Restoration, to John Corden of Herefordshire, who had served in a royalist one. Apart from the full-time nurses employed in Parliament’s military hospitals in London, many other women volunteered (or were coerced) to nurse sick and wounded soldiers. Very often these were poor widowed women, as parish officials always preferred to find paupers employment rather than pay poor relief. One widow who appears several times in the database is Rose Oldershaw of Nottingham, who over two years nursed Timothy Holt back to health. The cost of looking after wounded men involved significant time and money, as Ann Nixon intimated in a petition to the Nottinghamshire committee in 1646. If the patient was sick rather than wounded, infection was an obvious risk, as deadly diseases were prevalent in all armies. The smallpox epidemic which ravaged the New Model over the winter of 1645/6 is reflected in numerous documents submitted to county officials in Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire. An entry for Thomas Lucy of Datchworth, Hertfordshire, not only shows that the smallpox was brought into civilians’ houses, but also that it was often lethal [TNA SP28/232, fol. 714]. Smallpox afflicted the New Model again in 1651, as units passed through Essex, leaving sick soldiers in the care of the local community [Essex Record Office, Q/SBa2/78]. Given the prevalence of death in both military and civilian communities at this time, clergymen had a vital role to play. Those who served as regimental chaplains experienced all the privations of soldiering, and many were unable to last for even one campaign. William Dolman, chaplain to Colonel Alexander Popham, features in the Civil War Petitions database, and hopefully more will be found. Unlike surgeons, clergymen were often in considerable danger from those enraged by their religious views: Dr Michael Hudson, a notorious royalist cleric, met a grisly end, as did Hugh Peter, the equally notorious parliamentarian army chaplain. Some clergymen took an active part in the fighting, such as Samuel Kem, who served as a parliamentarian officer, and preached with pistols in the pulpit. Laurence Palmer, the rector of Gedling in Nottinghamshire, not only raised a troop of horse for Parliament but led it into battle. Even clergymen who did not carry swords could still die on them: Richard Benskin, rector of Wanlip, was killed by parliamentarian troops during the storming of Shelford in 1645. Catholic priests were killed during (or more likely after) the taking of Drogheda and Wexford. Clergymen were often engaged in espionage work, a shadowy and largely thankless occupation. Then as now, spies were often tortured and executed if caught, and they were rarely acclaimed by their own side even if successful. Stewart Beale’s blog on Katherine de Luke has already told the story of a rare petition from a civil-war spy. More normally, we are left with curt notes of summary executions, and little more. Occasionally, however, a petition will lift the veil of anonymity. William Bramley and his five siblings were orphaned when their father was executed by royalists at Wingfield Manor, presumably either before or during the siege of 1645 [TNA SP28/226, fol. 246]. Spies may have met ignominious ends, but their work arguably required more nerve and commitment than normal soldiering, and there is no doubt that ‘they also served’. Further reading John Ellis, To Walk in the Dark: Military Intelligence in the English Civil War, 1642-1646 (History Press, 2011). Eric Gruber von Arni, Justice to the Maimed Soldier: Army Hospital Care during the English Civil Wars and Interregnum (Ashgate, 2001). Anne Laurence, Parliamentary Army Chaplains 1642-51 (Royal Historical Society, 1990). W. G. Ross, Military Engineering during the Great Civil War (reprint, Ken Trotman, 1984). Eduard Wagner, European Weapons and Warfare 1618-1648 (reprint, Winged Hussar Publishing, 2014).

Read More

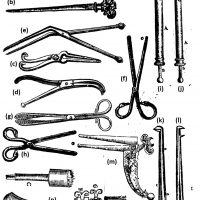

The personal cost of war: injuries from firearms and their treatment during the Civil Wars

This is the final instalment in our trilogy of blogs on medical care written for us by Prof. Stephen M. Rutherford of the University of Cardiff. It combines the themes from the first blog examining the physical impact of gunshot wounds with the themes from the second blog examining surgical effectiveness and survivability, to uncover how surgeons during the Civil Wars treated wounds from firearms during the Civil Wars... In his treatise on gunshot wounds published in 1628, John Woodall remarked that ‘No wound of Gun-shott can be said to be a simple’, a maxim that was eloquently reinforced by the experiences of soldiers in the British Civil Wars nearly two decades later. A substantial number of petitions in this project refer to wounds from firearms (muskets, pistols and/or cannon shot), many of which were serious enough to cause long-lasting disability, such as the loss of use of a body part (or actual loss in some cases), or chronic debilitating pain in an injured part of the body. For example, the case of Michell Powell of Wrexham, Denbighshire (10 July 1660), whose petition reported that he had been ‘shott in the right arme though beinge partly cured then: yett in the p[ro]cess of tyme festered agayne & soe corrupted yt it grew to be a woolfe or gangrene … payinge the Chyrurgion for cuttinge the sayd wolfe forth & beinge still in a lamentable Condyc[i]on through deadnes of flesh: hauinge his veynes & nerues shrank & knotted through the dolor therof’. This petitioner was rendered unable to work as a result of this wound, leading to extreme hardship: ‘hindred yo[u]r poore petyc[i]oners callinge beinge a taylor & hauing 5 smal children soe yt his wyfe was constrained to wander about the towne to collect the charytie of all well disposed people’. This petition demonstrates the severity of the wound, but also its subsequent physical and financial impact. Some wounds from firearms could be very extensive. The petition of former royalist soldier, Edward Bagshaw, of Conisbrough, West Riding of Yorkshire (3 August 1668) recorded that he was shot in the side of the body, but also received ‘many wounds & cutts in the head in somuch that yo[u]r petic[i]on[e]r had nine bones taken out of his skull, And all that nourished yo[u]r petic[i]on[e]r for three weekes he rec[eiv]ed in att a hole in the side of his head …’. With many conflicts being assaults upon, or siege actions of, towns and cities, soldiers were not the only victims of injuries from firearms. An unusual petition came from Jane Merrick of Upton Bishop, Herefordshire (dated 1661 to 1662), who reported that she herself was wounded by a cannon ball: ‘yo[u]r pet[itione]r when the scotts beseiged this Citty was wounded by a Cannon shott in th legg when as she was a doeinge servis for this Cittie a makeinge vp a breach w[hi]ch was in Wigmore streete’. Jane was so badly injured that she needed to be carried to safety by ‘Mr Hugh Rodd’ (for more on Merrick, see this previous blog by Lloyd Bowen). The damage from bullets was not the only danger. The gunpowder itself was also a significant risk, as most muskets used in the Civil Wars were matchlock muskets, loaded with loose back powder, and fired using a piece of burning ‘match’ cord. Royalist surgeon Richard Wiseman recalled the case of a musketeer, whose store of gunpowder ignited while filling his bandoliers (a strap across the body from which hung small wooden bottles, each containing sufficient loose gunpowder to load and fire the musket once) with disastrous consequences: ‘A Souldier in the time of service being in the Fort-Royall at Worcester, hastily fetched his Bonnet full of Gun-powder; and whilst he was filling his Bandeliers, another Souldier carelesly bestrides it, to make a Shot at one of the Enemies which he saw lying perdue. In firing his Musket, a spark flew out of the Pan, and gave fire to the Powder underneath him, and grievously burned the Hands, Arms, Breast, Neck and Face of him that was filling his Bandeliers. And as to himself, he likewise was burned and scorched in all the upper part of his Thighs, Scrotum, the Muscles of the Abdomen, and the Coats of the Testicles to the Erythroïdes, so that the Cremasters were visible. And indeed it was to be feared, that, when the Escar should cast off from his Belly, his Bowells would have tumbled out.’ The majority of wounds from gunshot, however, were likely to have been caused by the damage made by the entry of the musket ball (variously also termed the ‘bullet’ in primary sources). See the first blog of this trilogy for details of musket ball damage. Gunshot wounds were no longer novel, by the time of the Civil Wars, and had been described in published works by surgeons such as Thomas Gale (1563), William Clowes (1588), and John Woodall (1628, 1655). However, one might argue that the duration of civil-war conflict provided unprecedented numbers of this wound type in the British Isles. The longevity of the published works of two civil-war surgeons, James Cooke and Richard Wiseman, demonstrates the significance of their procedures. Wiseman’s opus, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises (1676), was reprinted in five editions up to 1745, and his work was still cited as the leading authority on gunshot wounds in Ballingall’s Outlines of Military Surgery (1844). While some treatments were effective, equally there were some wounds that were beyond help, as Wiseman recounted regarding one unfortunate patient who had been treated by another surgeon: ‘In the Wars I was called to see a poor Souldier, who had his Arm shot off near the Shoulder. The bruised and shattered Stump seemed to his Chirurgeon to be gangrened, and accordingly he drest him with Aegyptiac. as a Gangrene: from which sharp Dressings the Wound gleeted, and, by reason of the Pain, inflamed. He had roared some days through the vehemency of that Pain. When I came to him, I saw a great Trembling of the Part, and a frequent twitching upwards of the Tendons and Musculous flesh in the Stump; also the Flesh in the whole Stump was of a whitish colour, as if it had been scalded.’ The state of this wound was critical, and on this occasion, despite trying to control the deterioration of the tissue, Wiseman noted ‘but it was too late, he died howling’. This unfortunate soldier might have survived had his early treatment been different, since within the petitions shared by this project, there is evidence of similar wounds that were survived. The first blog in this series describes the physical damage caused by a musket ball. But how was this damage treated? The ball would penetrate the body causing internal damage via ‘permanent’ and ‘temporary’ cavities. However, unlike modern bullets, often there was no ‘exit wound’ from a musket shot, as the soft lead musket ball would potentially flatten or be diverted from its trajectory within the body. In this case, the surgeon would need to remove the bullet as part of the treatment. First the bullet needed to be found, a procedure best done by the surgeon inserting his finger, or a long metal probe, into the wound. The feel of metal touching metal was different to that of metal touching bone or sinew, and so a metallic bullet could be located using this method. On some occasions the outline of the embedded musket ball could be seen under the skin, in which case making a new incision in the patient was easier and safer for removal. Most commonly, the bullet was deep within the body tissues, and so needed to be removed the way it came in. Two forms of implement were used for retrieval. Firstly a ‘tirefond’ or ‘terebellum’ bullet extractor, which was a long thin implement, with a central baffle ending in a screw thread. The instrument could be inserted into the wound, and the screw-tip then drilled into the soft lead of the ball, before removal from the body. Alternatively, long forceps or pliers could be used, of which there was a wide diversity of shapes and modes of action, typically given descriptive names such as a ‘crow’s bill’, ‘crane’s bill’ and ‘lizard mouthe’ (Rutherford, 2018). A key consideration when removing the bullet was to also remove any fragments of clothing that were carried in when the bullet struck. As a musket ball was spherical, a small circle of cloth from the soldier’s clothing would potentially enter the wound. As Wiseman described, these fragments (from typically quite dirty clothing) could lead to serious consequences, including what we would now refer to as sepsis, or blood poisoning: ‘for the Bullet pierceth not any Part without carrying Rags along with it, which corrupt in the Wound … occasioning a prolonging the Cure’. Wiseman described two instances where contaminating rags caused problems for treatment. The first was the servant of a nobleman, shot by highwaymen, ‘yet was his Gun-shot more vexatious then all the rest, until I extracted the Bullet, and Rags carried in with it … I united and healed it in ten or twelve days, which I doubt would not have been cured in three months.’ Similarly, a wounded soldier, shot in the shoulder was treated by Wiseman: ‘After several unsuccessfull Applications, I made an Incision by the side of the Scapula into the Cavity, and pulled out the Rags that had been carried in by the Shot: and from that time all Accidents ceased, and the Wound cured soon after.’ Once the rags were removed, the wound could heal. Wiseman lamented that the lack of removal of rags from the wound would lead to poisoned wounds. He noted that ‘while any of the Rags remain in the Wound, it will never cure: but the extraneous bodies drawn out, there is little difficulty in the healing these Simple Wounds’. Once the wound was cleared of the bullet and any rags or contaminants, the bullet hole itself needed to be closed. This could either be done by means of a suture (a stitch), a ligature (tying off a wound using a thread or bandage), or cauterisation (burning of tissue). Cauterisation was a debatable activity, with some practitioners from the sixteenth century onwards arguing that it did more harm than good. But it is clear from published surgical treatises that reference the civil-war period, that cauterisation was still common practice. The use of an ‘actual’ cautery was most common (an iron structure which was heated in a fire), although the use of hot oil was also practiced, especially in previous decades, although Ambroise Paré of France argued against this particular practice. Cauteries had a c.12 inch long metal shaft ending in a specific shape (either a sphere, olive shape, rounded bar, or a flat disk), depending on the requirements of the wound. Cauterisation helped both seal and sterilise the open wound, but the after effects of the severe burn could potentially be as dangerous as the wound itself. Other methods for treating the wound were employed such as what is now termed ‘delayed primary closure’ (discussed in my previous blog), as well as poultices and ointments designed to encourage natural cleansing of the wound (a term referred to as ‘proper digestion’). The production of pus was seen as a good result, and indicative of wound healing. One of the most unusual of these digestives was a salve named ‘Oleum Catellorum’ (‘Oil of Puppies’). An ointment made by boiling newly-whelped puppies in lily oil, along with earthworms that had been clarified in white wine. Once boiled and strained, the liquid was mixed with terabinth (turpentine), and the resulting salve could be applied to a wound. How effective this salve was is not certain (and, ethically, is not something that we can test)! However, what is interesting is that the same recipe was reported as effective by both Ambroise Paré (who himself gained it from a colleague) in the 1500s and a century later by Richard Wiseman. These two authors regularly evidenced disdain of methodologies that they felt did not work. Gunshots might also shatter bones if the bullet struck them. The descriptions of fractures from gunshots shows that the authors of medical treatises had experience of the splintering effects of a bullet striking a bone. The remedy for this was advised to be the removal of the shattered pieces of bone, possibly leading to a resection of the limb (joining the two regions either side of the break back together), if the damage was not too severe. How successful this was is not commonly recorded, but its presence as a suggested treatment itself is telling. Wiseman described one extreme case of a soldier on a ship who, ‘had his right Arm extremely shattered about two fingers breadth, on the outside above the Elbow’. Wiseman recalled that ‘I would have cut it off instantly with a Razour (for the Bone being shattered, there needed no Saw:) but the man would not suffer me to meddle with his Arm’. Wiseman described in detail the treatment of the wound (Wiseman, pp. 427–9), which included setting the shattered arm using wetted pasteboard as a cast, ‘as it dried, stiffened, and retained its shape, preserving the Fracture in the position I left it, and that with a very slack Bandage.’ The recovery took several months, but the soldier retained his arm. If the limb could not be saved, then it would need to be amputated. This process is described in detail in Cooke’s Mellificium Chirurgie (1648). The flesh above the damaged region was cut using a sharp curved ‘dismembering’ knife, with the sharpened edge on the concave edge, so that the limb could be cut in a single movement. Cooke advised that this knife should be heated in a fire before-hand (which incidentally would have sterilised the blade). The flesh could then be pulled back, and the bone(s) severed using a sharp saw. Cooke advised that several saws should be kept to hand, in case of breakage, as speed was of the essence. Rather than cauterising blood vessels, Cooke advised that severed major vessels should be stoppered with small round buttons made of linen, and dipped in wine, then held in place by sutures or ligatures. The flesh of the stump could then be sewn shut, although the stress placed on the sutured region was possibly problematic. A better approach was to cut the flesh into pointed flaps which could be sewn against each other into a dome, but this was not adopted until later in the century. Amputation, usually undertaken while the patient was fully awake, was noted as being a last resort, but Cooke himself emphasised that ‘Dismembering is a dreadful Operation; yet necessary’. Survival of an amputation was likely to be proportionate to the prominence of the region amputated (records in later centuries note that survival was higher for removal of digits, hands/feet, or extremities of limbs, with lower survival for amputations of the thigh or upper arm). However, an extreme example of John Tinckler of Durham, a gunner at Hartlepool, who lost his sight and both his arms, and yet survived, as well as the prominence of severed limbs and hands or feet in the petitions from soldiers illustrates that it was possible to survive amputation. The impact of these wounds was not only physical, and causing long-term implications for a wounded man’s ability to support himself and family, but it also impacted the soldier by means of the cost of the surgeon’s care. Although in many cases surgeons were in the pay of regiments on both sides (Pells), local civilian surgeons would charge for their services in garrison towns or once a soldier had been discharged from service. The petition of Elizabeth Newum, Nottinghamshire (20 December 1645) described the cost of treatment of her late husband, Nathaniell, as ‘the sume of foure pounds or vpward to bee paid vnto the surgion and Pothecarie whom dayly come upon mee’. Elizabeth was being hounded for payment for her husband’s care, and reported being ‘forct to sell vp all that I have and soe I and my poore infant shall bee forced to beg’ in order to cover the cost of the treatment. Some treatments could last for many days, weeks, even months, and thus would incur considerable costs. Christopher Ellin of Black Notley, Essex, had reported in his petition to the Essex county sessions (1652) that he was shot with a musket ball during the Battle of Worcester (3 September 1651), which struck him: ‘…in one of his Armes of which wound he hath lyen almost ever since under the Chirurgeons hands in the Savoy Hospitall at London.’ Another example, Tobye Ganbran’s petition to the City and County of Gloucester (17 November 1643) records that he was ‘sorely hurte and wounded with a mvskett shott, and thereby constrainde to lye vnder the Surgeons hands to be cured (this sixe weekes) and is not it perfectlie cured, w[i]th the Charge thereof hath cost him a greate deale of money, as vnto the Surgeon xx s., besides attendance, diett, and other necessaries.’. Similarly, the petition of Peter Green (27 August 1646) to the Nottinghamshire county committee noted that ‘y[ou]r poor petic[i]oner was lately wounded in the belly by a shot from the Enemye whereof hee lay many weekes under the Chryrugeons hand to his great paine & charges’. The petition records that ‘(notwithstanding the Chyrugeon is yet unsatisfied for his great Care & wonderfull Curre)’. It is noteworthy that these petitions, each of which were proximal to the date of the wound, refer not so much to the disabling impact of the injury, but rather to the financial charge incurred from several weeks of treatment, which the soldier was expected to pay. Wounds from firearms required particular treatments, and these treatments appear to have been reasonably effective. Unfortunately, it is not possible to clearly gauge the ratio of how many soldiers died outright compared to those who died from their wounds, or as a result of treatment, versus those who survived. But there were clearly effective methods for dealing with some quite extreme injuries. The existence of petitions from maimed victims of gunshots many decades after the wound was inflicted, shows that seventeenth-century soldiers could both survive, and live with, significant injuries from firearms. Primary Sources G. Ballingall, Outlines of Military Surgery (Edinburgh: A&C Black, 1844). W. Clowes, A Prooued Practise for all Young Chirurgians, concerning burnings with Gunpowder, and woundes made with Gunshot, Sword, Halbard, Pyke, Launce, or such other (Thomas Orwyn, 1588). J. Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgie, or, The Marrow of many Good Authours (London, 1655). J. Cooke, Supplementum Chirurgiae, or the supplement to the Marrow of Chyrurgerie (London, 1655). J. Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiae, or the Marrow of Chirurgery much enlarged (London, 1676). T. Gale, Certain Works of Chirurgery, Newly Compiled (London, 1563). A. Paré (T. Johnson, translation), The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey translated out of the Latine and compared with the French (London, 1634). A. Paré (W. Hammond, translation), The Method of Curing Wounds made by Gun-shot. Also by Arrowes and Darts, with their Accidents (London, 1617). R. Wiseman, Severall Chirurgical Treatises (London: Norton and Maycock, 1676). J. Woodall, The path-way to the Surgions Chest (London, 1628). J. Woodall, The Surgeons Mate or Military & Domestique Surgery (London, 1655). Secondary Works E. Gruber von Arni, Justice to the Maimed Soldier: Nursing, Medical Care and Welfare for Sick and Wounded Soldiers and their Families during the English Civil Wars and Interregnum, 1642-1660 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001). G. Keynes (ed.) The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, 1585 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952). I. Pells, ‘Reassessing frontline medical practitioners of the British Civil Wars in the context of the seventeenth-century medical world’, The Historical Journal, 62:2 (2019), pp. 399–425. S. M. Rutherford, ‘Ground-breaking pioneers or dangerous amateurs? Did early-modern surgery have any basis in medical science?’, in I. Pells (ed.), New Approaches to the Military History of the English Civil War (Stroud: Helion and Company, 2016), pp. 153–85. S. M. Rutherford, ‘A new kind of surgery for a new kind of war: gunshot wounds and their treatment in the British Civil Wars’, in D.J. Appleby and A. Hopper (eds), Battle-Scarred: Mortality, Medical Care and Military Welfare in the British Civil Wars (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), pp. 57–77.

Read More

Wounds, battlefield trauma, and their survivability in the British Civil Wars

This week's blog is the second in a trilogy of blogs which have been written for us by our colleague Professor Stephen M. Rutherford of the School of Biosciences, Cardiff University. His previous blog used examples drawn from Civil War Petitions to illuminate the nature of the physical damage inflicted on the body by gunshot wounds sustained during the Civil Wars. This instalment uses the evidence from Civil War Petitions to discuss the tricky issue of surgical effectiveness and survivability... Corporal John Barret of Captain Cotton’s Company, on the Parliamentarian side in a skirmish at Painswick, Gloucestershire, 1644, suffered a horrible fate at the hands of the enemy. Shortly afterwards, he reported to the Parliamentarian Governor of Gloucester, Colonel Edward Massey (signed Massie in the petition), who then endorsed his petition, that he had been set upon by two cavalrymen and six infantrymen, whereupon he was cut ‘downe and left for dead: and having receaved Tenne wounds of them [they] stript me starck nacked to the very skine’. He reported that ‘ever since that time I have layne bedrid under the Cyrurgions hands and now I being able to rise I can not for want of Cloths’. Colonel Massey confirmed that John had ‘receved 7 wounds in the head 5 of them therow the scull [one] cut in the backe (to the bons [bones]) with a pole axe his elbow cut off bons and all: his hand slitt downe betwine the fingers.’ We do not know whether Corporal Barret survived these wounds long-term, but he certainly survived long enough to make the petition, and described his effective treatment: ‘Mr Caradine the Cyerrugion [surgeon] afermeth who hath almost Cured them al (and very car[e]fuly and willingly he hath taken the pains to do it) how to satisfie him we know not he was never the man that asked us a farthing.’ The extent of Corporal Barret’s wounds were extreme – including scalping the skull down to the bone, as well as a bone-deep cut in the back, several other wounds, and the loss of an arm. The fact that he did not die on the battlefield is remarkable, but the fact that he survived long enough to petition the Governor for clothes and means to repay the surgeon show clearly the capability of surgeons in the British Civil Wars. The injuries treated by Mr Caradine were more extreme than some modern day military wounds, and yet he lived to tell the tale. Surgeons and physicians in the early modern period have gained a reputation in the popular mind as savage butchers with little or no understanding of medicine. However, recent historiography in this area – especially the work of Ismini Pells on Civil War military surgeons (Pells, see also Rutherford, 2016 and 2018) has highlighted that surgeons in this period did undertake procedures that had substantial merit in biomedical terms. Indeed many of the procedures pioneered in this period are still in use in modern military medicine today (Rutherford, 2018). Far from being unskilled and ineffective, there is evidence of early modern surgeons practicing a form of ‘Evidence-based Medicine'. That is using empirical evidence of their experiences and reports to guide and refine medical practice. Such practitioners included Ambroise Paré, sixteenth-century surgeon to the Kings of France, James Cooke, Parliamentarian surgeon during the Civil Wars, and Richard Wiseman, personal surgeon to Charles Prince of Wales, and later Sergeant Surgeon to him as King Charles II. The following video demonstrates the extent to which a cheap sword, quality sword, and dagger could injure a human limb (the video uses a leg of meat as an equivalent substitute): From this video you will see that even a cheap, mass-produced sword wielded by an inexperienced swordsman, could potentially cut several inches into an unprotected limb. A heavier, better quality sword was capable of a cut of 10-15cm in depth, and about 20cm in width – easily sufficient to sever a limb or cut into an unprotected skull. Battlefield archaeology from earlier conflicts, such as the Battle of Towton in Yorkshire (1461), or the Battle of Visby in Sweden (1361), display numerous examples of severed limbs and cuts deep enough to slice or shatter bone. Even if the limb was not shattered, the cut would be deep enough to make repair difficult or potentially impossible. The challenge to a military surgeon, therefore, was considerable. Without the proper medical records it is not possible to determine the survival rate of injuries suffered by Civil-War soldiers. What can be inferred, however, is some degree of effectiveness of surgical procedures from the evidence of the extent of wounds survived by Civil-War soldiers. In the archaeological finds mentioned above, there were examples of skeletons of persons surviving quite catastrophic injuries (severed or broken limbs, sword cuts deep enough to scar the bone, for example) long enough for those injuries to heal and the bones to fuse or produce new growth. The petitions uncovered and transcribed as part of this project give some valuable insights into both the wounds suffered by soldiers (and some civilians) in the Civil Wars, and also the extent to which these wounds were potentially survivable, after effective medical care. For example, the certificate for William Gray of Braintree, Essex, (8 April 1657) reported that he was ‘very much Debilitated in his limbs’, and that his ‘Legge hath beene brocken in many peeces’, and yet appears to have healed sufficiently for it not to need to be amputated. Another petitioner, John Ellis, of Dewsbury, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, reported (October, 1674) that he had received ‘received severall Wounds in severall partes of his body’, claiming that these had made him ‘impotent, lame and [decrepid] not able to worke for a livelihood’. William Sudbury of Woodnewton, Northamptonshire was reported (while requesting an increase to his pension, Trinity, 1674) to have received ‘13 wounds in his head & body very dangerous, but also the fingers of one of his hands cut [off]’. These substantial injuries disabled William from making a living, but the fact that he was able to survive such extreme damage to his body is quite remarkable. David ap Jevan of Bersham of Denbighshire (certificate dated 20 September, 1663) also had digits cut from his (left) hand, sufficient wounding to stop him being able to make a living for himself, but a wound that he survived for at least 20 years after his initial injury (at Holt Bridge in November 1643). These would have been wounds received on a dirty battlefield, and which would have been treated either in situ, or close by at a lodging. The patient would need to survive potentially catastrophic blood loss and shock at the moment of injury, and then also survive the potential infection of the wound at a time long before the discovery of antibiotics. A review of the approaches adopted by early modern surgeons (in particular military surgeons) highlights that there was a good level of understanding about suturing or bandaging of wounds, and the control of post-operative infection. There were a range of different suture methods, described by authors, such as Wiseman and Cooke, each with a specific wound type to be used for. There was also a range of ligatures (use of bandages to seal wounds) adopted as an alternative approach. Antibacterial agents, such as alcohol or posca (a water/vinegar mix) were used on equipment and bandages. Egg albumen or honey (the latter's high-sugar concentration being a natural antibacterial agent) were used as salves to keep the wound healthy. Even though in the seventeenth century there was no understanding of the biology behind microbial infections, the surgeons were aware of the effectiveness of these approaches, and even disdainful of other, less-effective methods. The efficacy of many of their approaches has stood the test of time, and are still in use in modern medicine. For example, in the post-operative management of infections, a common strategy was to leave the wound un-sutured and open for several days, the tissue kept apart by a ‘tent’ (a roll of bandage inserted into the cut). The wound was left until the flesh was ‘like flesh long hang’d in the air’ (Wiseman, p. 428). This approach, termed in modern medicine ‘delayed primary closure’ is in common use today for the treatment of conditions such as appendicitis, compartment syndrome, and some military injuries, most recently in the wars of Afghanistan and Iraq (Leininger, Rasmussen, Smith, Jenkins and Coppola). This approach for encouraging the body to treat its own infection (the theory - which even today is not confirmed - is that the open wound encourages the flow of lymph, which in turn encourages that accumulation of white blood cells and stimulates the immune response at the wound site) is seen in medical manuals from the mid-sixteenth century, and in manuals from numerous major conflicts over the subsequent centuries (Rutherford, 2016). Recovery from extreme injuries was slow and uncertain. Details of the extensive hospital care provided to some soldiers in the Civil Wars have been researched extensively by Eric Gruber von Arni, who revealed what was often an organised and systematic process of patient care, not least of which was the high calorific intake for patients, to aid their recovery. But the experience recorded in the certificate for Thomas Wayte of Doncaster in the West Riding of Yorkshire (March 1668) illustrates the extensive nature of this recovery period. It was reported that Thomas ‘resaiued [received] such desp[e]rate wounds, that he lay most dangerously on them for three or foure years together.’ This long-term need for care, and the requirement for support of disabled soldiers after their recovery, was frequently down to their families and community, as Ismini Pells and David Appleby have discussed in their blogs on this website: ‘Old Wives’ Tales: Long-term Medical Care during the English Civil Wars’ and ‘Members of one another’s miseries’: care in the community during and after the Civil Wars’. It is clear from these petitions that soldiers did survive catastrophic and life-changing injuries, often living with them for decades after they were inflicted. The physical and mental challenges of living with disabilities caused by traumatic injuries would have been considerable. It is remarkable, however, that soldiers with such extensive injuries survived at all, and a re-evaluation of the medical practices, and their effectiveness, of early modern surgeons has the potential to reveal significant insights into the development of surgical procedures, and the extent of their medical validity. It is a trope that ‘war drives innovation’, and this may well be true for the pioneering surgeons and medical practitioners in the British Civil Wars. One wound type, mentioned in my previous blog, that was of major significance in the Civil Wars was injury from gunshots. Injuries from such wounds were another challenge entirely, and the third blog in this series will look at the approaches taken for their treatment. References and further reading For further reading into the practitioners of medicine and surgery in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, an excellent resource is the Early Modern Medical Practitioners Project at the University of Exeter. This project has a range of different foci on early modern medicine, including cataloguing as many examples of named medical practitioners as can be identified. Primary Sources J. Cooke, Supplementum Chirurgiae, or the supplement to the Marrow of Chyrurgerie (London, 1655). J. Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiae, or the Marrow of Chirurgery much enlarged (London, 1676). A. Paré (T. Johnson, translation), The workes of that famous chirurgion Ambrose Parey translated out of the Latine and compared with the French (London, 1634). R. Wiseman, Severall Chirurgical Treatises (London: Norton and Maycock, 1676). Secondary Works E. Gruber von Arni, Justice to the Maimed Soldier: Nursing, Medical Care and Welfare for Sick and Wounded Soldiers and their Families during the English Civil Wars and Interregnum, 1642–1660 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001). B. E. Leininger, T. E. Rasmussen, D. L. Smith, D. Jenkins and C. Coppola, ‘Experience with Wound VAC and Delayed Primary Closure of Contaminated Soft Tissue Injuries in Iraq’, Journal of Trauma Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, 61 (2006), pp. 1207-11. I. Pells, ‘Reassessing frontline medical practitioners of the British Civil Wars in the context of the seventeenth-century medical world’, The Historical Journal, 62:2 (2019), pp 399-425. S. M. Rutherford, ‘Ground-breaking pioneers or dangerous amateurs? Did early-modern surgery have any basis in medical science?’, in I. Pells (ed.), New Approaches to the Military History of the English Civil War (Stroud: Helion and Company, 2016), pp. 153–85. S. M. Rutherford, ‘A new kind of surgery for a new kind of war: gunshot wounds and their treatment in the British Civil Wars’, in D.J. Appleby and A. Hopper (eds), Battle-Scarred: Mortality, Medical Care and Military Welfare in the British Civil Wars (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), pp. 57-77.

Read More

‘Manie dangerous woundes and shotts’: The physical impact of gunshot wounds in the British Civil Wars