HIGHLY COMMENDED IN THE BRITISH RECORDS ASSOCIATION’S JANETTE HARLEY PRIZE 2020:

https://www.britishrecordsassociation.org.uk/press-release-winner-of-the-2020-janette-harley-prize-announced/

The Scottish Connection

Over the duration of our project we aim to identify, digitise and transcribe literally thousands of petitions and other documents related with ex-soldiers and bereaved families from the Civil Wars. The project will focus on the counties and boroughs of seventeenth-century England and Wales (although we are already liaising with Irish and Scottish colleagues, with eye to future projects). Even in the heart of England, however, as David Appleby has found whilst researching Nottinghamshire, there is plenty of evidence to show that the so-called ‘First English Civil War’ of 1642-1646 was never solely an English affair... When fighting broke out in England in 1642, both King and Parliament solicited the services of professional Scottish officers. A more formal intervention came in January 1644, when the Scottish Covenanters sent a large army over the border in support of their English co-religionists in Parliament. At first, parliamentarian commanders such as Fairfax and Cromwell cooperated well with the Covenanters led by the earl of Leven and General David Leslie. The two allies even formed a ‘Committee of Both Kingdoms’ to coordinate their mutual war effort against Charles I. Gradually, however, tensions emerged. With the rise of the Independents, and the corresponding eclipse of the pro-Scottish Presbyterian interest within Parliament, Scottish soldiers were made to feel less and less welcome. As parliamentarian subsidies dried up, Leven’s army was starved of money, ammunition and food, and forced to live off the land. Scottish commissioners accused the Independent faction within Parliament of withholding funds deliberately in order to make the Covenanter army unpopular with English civilian communities. Charles I clearly intended to exploit his enemies’ divisions when he delivered himself to Leven’s army then camped around Southwell, Nottinghamshire, in May 1646. In the event, the Covenanters used the king as a bargaining chip to prise £400,000 from Parliament. Having handed him over to their erstwhile English allies the Covenanters marched back to Scotland in February 1647. Many of the Scottish soldiers would return to fight in England in 1648 and 1651. The impact of these political and military machinations on ordinary people’s lives can be seen in petitions such as that of a parliamentarian cavalry trooper named Joseph Curtis. Curtis’ petition to the Nottinghamshire authorities in 1647 detailed how, whilst he had been serving with Colonel Francis Thornhagh’s regiment, his home and possessions had been looted first by royalist enemies then by Scottish allies; the former causing him £100 in losses and the latter £53 9s, for which he received only five pounds by way of compensation (TNA, SP 28/241, fol. 1352). The Scottish Covenanters, meanwhile, lost many men dead and wounded in the fighting in Nottinghamshire, particularly whilst besieging the royalist stronghold of Newark. Several documents detail the expenses of nursing sick and wounded Scots in and around Nottingham (e.g. SP 28/241, fol. 84). Not all Scottish soldiers were able to leave when the Scottish army marched away from Southwell with their royal prisoner: the petition of one Nottinghamshire widow, Anne Nixon of Barthley, shows that as late as September 1646 she was still caring for a Covenanter named James Scott. Scott had been wounded months earlier, during the siege of Newark, and was still too ill to move. Just as Leven’s army had been starved of money by Parliament, so Widow Nixon was being forced to provide for the wounded man out of her own meagre funds. To its credit, the Parliamentary Committee for Nottinghamshire did belatedly allow her some financial relief (SP 28/241, fol. 722). Extra money was provided to enable James to journey north to re-join his army, as it had been for another Scottish soldier, Willy Scott, in May that year, who had ‘been long wounded here’ (SP 28/241, fol. 114). Most poignant of all was the petition of William Moffett in October 1645. Moffett had come down with Leven’s army, but had somehow ended up under local English command, in the infantry company of Major Joseph Widmerpole. The petition details that having suffered a bad fall, his injuries had proved too complicated for the local surgeons, leaving Moffett ‘in danger to be a cripple so long as he lives’. William pleaded for help from the Parliamentary County Committee, reminding them that he was ‘far from his country and friends’ (SP 28/241, fol. 531); a sad fate which has befallen so many wounded soldiers throughout history’s wars.

Read More

Archival Material now on Civil War Petitions!

So Civil War Petitions is now fully up and running! With images and transcriptions of original documents, exhaustive calendars of payment records gathered from the archives, and an array of different ways of searching the documents and records to interrogate them further, Civil War Petitions promises to provide comprehensive coverage of military welfare in England Wales during and after the Civil Wars. For a full guide to the type of material that you will be able to find on Civil War Petitions, visit the About the Data page. For a full explanation of some of the terms used, visit the Glossary. However, Civil War Petitions is very much still a work in progress! The research team have been working hard, travelling all over the country to gather data. So far, we have material on Civil War Petitions from the following counties: Denbighshire Dorset Durham East Riding of Yorkshire Essex Gloucestershire Hampshire Town and County of Kingston-upon-Hull Town and County of Newcastle-upon-Tyne North Riding of Yorkshire Northumberland Worcestershire West Riding of Yorkshire City and County of York Unsurprisingly, the survival rate for the documents is patchy, depending on the locality. Not all counties have any surviving petitions or certificates, or a complete set of order books or treasurers’ accounts for the payment records. However, the team have gathered any relevant data from the material still in existence. Not all of the data gathered so far has been uploaded to Civil War Petitions. The counties finished uploading all the data for are: Durham Essex Hampshire Town and County of Kingston-upon-Hull Town and County of Newcastle-upon-Tyne Northumberland City and County of York A few additional payment records need to be added for Dorset, East Riding of Yorkshire and North Riding of Yorkshire. A few additional petitions need to be added for Worcestershire. This work will be completed over the next few weeks. Large numbers of petitions and certificates have been found in Denbighshire (over 300!), as well as extensive treasurers’ accounts for this county, whilst the West Riding of Yorkshire also has a large number of petitions and certificates (over 100) and very extensive order books. Gloucestershire has a smaller number of petitions and certificates (19), as has North Riding (23). The completion of these four counties are very much our immediate focus and will be added as a series of mini-updates over the next quarter. Do keep an eye on our Twitter and Facebook feed for news of when these have been added. The project will thereafter upload further archival material in a series of quarterly updates. The counties which you can expect to see coming soon include: Berkshire City and County of Bristol Herefordshire Lincolnshire Nottinghamshire In addition, we expect Civil War Petition’s mapping functions and better graphics for the Events and Injuries pages to be ready later this autumn. Civil War Petitions was officially launched by the project team at the National Civil War Centre on Thursday 26 July 2018. We were delighted to welcome academics, university staff, students, archivists, school teachers, museum professionals, representatives of modern military welfare charities, descendants of leading Civil War families and local government officials amongst our guests. All have been, or soon will be, involved in some way in our project and we would like to thank everyone who has in some way supported us. We were entertained throughout the evening by the wonderful ‘Diabolus in Musica’, seventeenth-century period costumed musicians who regaled us with a variety of contemporary music. They did a fabulous job of uplifting the spirits of any who might have been flagging under the heat of the hottest day of the year! We were also extremely honoured to have a special performance from the Waddington branch of the Military Wives Choir. Before the performance, one of their members shared her experiences of being a military wife and explained what it meant to be part of the armed forces family. She spoke of supporting her husband through unsocial working hours, a constant peripatetic lifestyle and the uncertainty brought about by deployment – all these are timeless themes to military partners across the centuries and a poignant reminder of the anxieties and certainties that must have been experienced by families during the Civil War, as well as the comfort that can be drawn from the wider military community. We are very grateful to Carol King, Business Manager of the National Civil War Centre and her team for hosting us and helping us put on such an enjoyable evening. If you have any comments, questions or enquiries about Civil War Petitions, please feel free to either email us via civilwarpetitions@le.ac.uk or contact us via our Twitter or Facebook pages.

Read More

Dead and buried? The fate of the Civil War battle-dead

In a previous blog, Andrew Hopper revealed the military and political uses of wounded survivors and prisoners of war from Civil War encounters, but what became of those of did not live to tell the tale of the fighting they had experienced? This week, Civil War Petitions welcomes a guest blog from Sarah Taylor, who uncovers the murky story surrounding the disposal of the dead... Although military historians have, in recent years, increasingly turned to studying alternative aspects of battles other than just their tactics or wider political impact, one aspect that has still been largely ignored is what happened to the bodies of those killed in battle. On looking at the sources, it is not all that surprising that this topic has received so little attention. Most sources avoid the topic, while of those which do mention the disposal of the dead, many do so incidentally. Following the battle of Edgehill (23 October 1642), for example, one source writer claimed that the Royalists had ‘about 3000 of theirs slain’ as he had been ‘informed by the Countrie men that saw them burie the dead next day’ (Thomason Tracts E.124[32]). The writer’s interest was not in what had happened to the bodies but in how severe the opposition’s losses had been. Quite a few of those sources which do refer to the disposal of the dead appear to do so because of a matter of honour (that is, someone had acted with particular honour or, more likely, with particular dishonour). Parliamentarians after the battle of Hopton Heath (19 March 1643), for example, tried to ransom the body of the Royalist commander back to his men in exchange for the prisoners and weapons that the Royalists had captured in the battle. One Royalist source describing the incident accused the Parliamentarians of ‘barbarisme and inhumanity’ and that their actions were ‘ignorant of what belonges to the honour of a souldier’ (D686/2/69). The commander’s own son was present and he, in a letter to his mother, sounded quite baffled when talking about this action which was ‘never before heard of in any warre’ (E.99[18]). Given the unusual and dishonourable nature of the incident, it is not at all surprising that source writers felt the need to mention it. Another notable encounter was the first battle of Newbury (20 September 1643), where a Royalist source described how ‘severall heapes of [the Parliamentarian’s] dead were found cast into Wells, Ponds and Pits, one Draw-well of 30 fathoms deepe being filled to the top with dead bodies…and in sundry places with armes and legges sticking out besides those above ground whom [the Parliamentarians] had not time to cover’ (TT E.69[18]). One Parliamentarian source actually responded to these ‘wilde relations’, claiming that since they had fought close to a river a well would not even have existed in such a place, let alone that the Parliamentarians would throw their dead down it (TT E.250[17]). The very fact that the Parliamentarians felt the need to respond to the claim suggests that disposing of one’s dead in such a manner was not acceptable, and that the Royalists may have been trying to use the dead as propaganda, to slander the Parliamentarians and their reputation. It does seem unlikely that the Parliamentarians would have thrown their dead into a well, particularly as the Parliamentarian commander had already ordered the locals to finish burying his dead; while it seems unlikely that the Parliamentarians would have wanted to alienate the locals by blocking their water sources, since they were reliant on the people for support and resources, like food, men and equipment. As for where the dead were buried, the sources are again very tight-lipped. A number of sources talk about high-status men being taken to churches for burial but because they say little about the rank-and-file, it is very difficult to judge if, and to what extent, those high-status men were being treated differently to the rest of the dead. It is clear that not all high-status men were buried in a church: letters by one man lament how he was unable to locate the body of his father, who had been the Royalist standard-bearer, after the battle of Edgehill so that he could take it for a church burial (Verney letters). The same letters noted how one lord ‘was like to have been buried in the fields, but that one came by chance that knew him and took him into a church, and there laid him in the ground’, highlighting how, sometimes, it was down to chance and one’s friends and family to find and remove a body for a church burial. If this was the case, then it seems quite likely that some common soldiers may also have received a church burial, particularly if they had friends or family nearby who were able to find their body and to convey it to a church. This lack of information is very problematic. Clearly some of the dead were being buried in churches, but what about everyone else? There are a few historical sources that confirm that some of the dead were buried on or near the battlefield, such as the one above, which mentioned the dead being buried ‘in the fields’. A churchwarden’s account also records how some of the dead from the first battle of Newbury were buried on the battlefield, as well as in the churchyard. This suggests that some of the dead were buried on the battlefield, a picture that some of the archaeology would seem to support (although even much of this is shaky because it is so hard to explicitly link burials to a specific event). Burials have been reported on Naseby battlefield since near to the time of the battle, for example. Overall, the evidence is very patchy: certainly some of the dead were buried in churches following a battle, while others seem to have been buried on the battlefield. It is not certain that both of these things occurred at all battles, though. The character or nature of a battle could certainly have had an impact. Much of the battle of Worcester (3 September 1651), for example, was fought within the town; while church records note that lots of those who were killed in the town were then buried in churches in the town, so the location of a battle may have had an impact on where the dead were buried. The numbers of bodies might also have had an impact. If there were lots of bodies, then we might expect that more of the dead were buried on the battlefield simply because it was too difficult to move so many bodies to a church which would not have had the space anyway. Battles where few men were killed, on the other hand, like Hopton Heath, may have led to many men being taken to a church for burial, rather than being buried on the battlefield. Sadly, the lack of detail in the historical sources makes it difficult to say much and it seems only with more archaeological finds will we truly start to understand where the dead were buried and why. Sarah Taylor is a third-year PhD student at the University of Huddersfield, funded by the Heritage Consortium. She is researching what happened to the bodies of those killed in battle, covering the period which includes the Wars of the Roses and the Civil War.

Read More

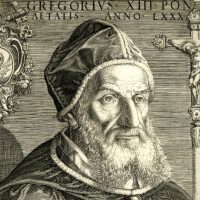

A Brief History of Time (in Civil War Petitions)

As explained elsewhere in this website, the project team is currently hard at work locating and transcribing thousands of documents which will eventually be made freely available via this website. In addition to these verbatim transcriptions, the team aims to produce a modernised text version of each document. However, even modernised texts can still be confusing, not least because of the various ways in which time was measured in the seventeenth century. Here, David Appleby sketches out the chronological minefield, and finds that the text of some petitions suggests that the poorer and middling sorts of people tended to mark the passing of time rather differently from the social elite... In February 1582, Pope Gregory XIII issued a decree to remove ten days from the calendar. He further ordered that every year thereafter should commence on 1 January. Gregory’s intent was to reduce confusion by aligning the calendar year more closely with the solar year. However, reflecting the bitter religious divisions in Europe at the time, Protestant states such as England pointedly continued to use the old-style Julian calendar (so named because it had been established by Julius Caesar in 45BC/BCE). This meant that throughout the whole of the seventeenth century, the calendar year in the British Isles began on 25 March, rather than 1 January. The festival of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin had long since ceased to be observed in Protestant England, so 25 March was known simply as ‘Lady Day’. Even in the seventeenth century, many English people (particularly those trading with Europe) were beginning to consider the Julian system inconvenient but it was not until George II’s reign that the ‘New Style’ dating was written into law. Following a vote in Parliament, it was declared that 1752 would begin on 1 January. The potential for confusion caused by the clash of these ‘Old’ and ‘New’ styles was never better demonstrated than in 1813, when workmen accidentally broke through the wall of a vault under St George’s chapel in Windsor. On investigation, it was found that one of the coffins in the vault contained the body of King Charles I. The engraved silver plate on the coffin lid recorded that the king had met his end in 1648 – whereas, by the modern (post-1751) calendar, he had actually been executed on 30 January 1649. Interestingly, a commemorative stone laid in the chapel in the nineteenth century copied the date on the coffin plate, again suggesting that Charles had died in 1648. Did those who commissioned the marble slab do this deliberately, or were they unaware of their error? Even professional historians are sometimes caught out. A common method used by historians and archivists to avoid confusion between ‘Old Style’ and ‘New Style’ dating is to transcribe any affected dates by noting both years. The date of Charles I’s execution might therefore be transcribed as 30 January 1648/9. This method was already in use in the seventeenth century for precisely the same reason. Officials who did not take such precautions sometimes got themselves in a muddle: one Nottinghamshire Parliamentary Committee warrant to pay an officer’s widow named Anne Nethercotes was erroneously dated ’28 March 1645’, despite the fact that it was clearly issued on 28 March 1646. It seems that the scribe forgot that Lady Day had come and gone, and that the new calendar year had started. The Georgian Act of Parliament which confirmed 1 January as the first day of the year also brought the British calendar into line with its Gregorian counterpart. Taking leap years into account, the discrepancy was even greater than it had been in Pope Gregory’s time, so Parliament ordered that 2 September 1752 be followed by 14 September. It is often claimed that the poorer sort rioted and demanded that the lost days to be restored to them, but there is no tangible evidence that such disorder ever took place. Red-letter dates, such as 5 November (Bonfire Night) and 30 January (the anniversary of the Regicide), remained untouched, although strictly speaking all should have been moved by the requisite number of days. Historians have generally followed this convention without comment. The only real problem arises when researchers have to deal with an exchange of letters between British and Continental correspondents, when it can sometimes seem that letters are being replied to before they have even been written! Another chronological trap hidden in the quarter sessions minute books concerns the regnal years of Charles II’s reign. Restoration officials habitually pretended that the ‘Interregnum’ (i.e. the Commonwealth and the Cromwellian Protectorate) had never happened, dating Charles II’s accession from the death of his father on 30 January 1648/9, rather than the restoration of the monarchy in May 1660. In such circumstances, the ‘Old Style’ Julian calendar reinforced efforts to recreate the pre-war ancien regime. All of which explains why the preamble to the Michaelmas quarter sessions in Essex in October 1660 notes that the court is being held in the twelfth year of the king’s reign – implying that the reign had commenced in 1648/9. In contrast to the exact, often politicised calendar utilised by the gentry, phrases used in the petitions of maimed soldiers and war widows suggest that the common people still tended to mark the passing of time with more traditional milestones. It is particularly interesting to see the survival of traditional Catholic terminology in popular Protestant discourse. Winifred Badge, who petitioned the Parliamentary County Committee for Nottinghamshire on 30 January 1644/5, stated that her husband had been slain ‘on Lamass Day’ whilst besieging Wingfield Manor. Lamas, or ‘loaf-mass’ was an old Anglo-Saxon festival, Lamas Day itself occurring on 1 August. Lamas loomed large in the lives of common country folk not least because it was traditionally the time on which certain privately-owned land had to be opened up to common grazing. It is equally revealing that the term ‘Christmas Day’ surfaces in a petition submitted by Thomas Collishaw of Bilborough, Nottinghamshire, in April 1648. The petition declared that in addition to his own sufferings Collishaw desired recompense for a horse which he had bought on Christmas Day 1642, and had ridden ‘all Christmas’ until it fell lame. Collishaw – and the amanuensis who wrote the parliamentarian cavalry trooper’s petition – were presumably aware that Christmas, Easter and Whitsun had been banned by Parliament in June 1647, on the grounds that the three festivals had no basis in Scripture, and were therefore sinful. Of course, the Civil Wars gave maimed soldiers and bereaved families new and more distressing milestones with which to mark the passing of time. These milestones included not only the bloody consequences of huge set-piece battles such as Edgehill (1642), and sieges such as the two at Lichfield in 1643, but also bitter fighting for relatively obscure places such as Wingfield Manor (Derbyshire, August 1644) and Shelford House (Nottinghamshire, November 1645). The course of some people’s lives would be changed by otherwise inconsequential incidents. It is very doubtful whether Martha Emming of Coggeshall, Essex had previously heard of Heslington in Yorkshire, but she would forever remember it as the place where her husband Daniel was killed. The evidence suggests that he was one of the ‘five or six’ hitherto nameless parliamentarian soldiers who died there on 6 June 1644, as Parliament’s Eastern Association army probed York’s outer defences. Recommended reading: R. Cheney (revised Michael Jones), A Handbook of Dates for Students of British History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). David Cressy, Bonfires and Bells: National Memory and the Protestant Calendar in Elizabethan and Stuart England (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2004). Keith Wrightson, ‘Popular senses of past time: dating events in the North Country, 1615-1631’, in Michael Braddick and Phil Withington (eds.), Popular Culture and Political Agency in Early Modern Britain (Woodbridge, 2017), pp. 91-107.

Read More

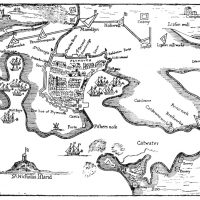

The Story after the Battle Before: The Wounded Prisoners of Seacroft Moor

Many accounts of Civil War military encounters end their stories with the numbers of the dead, wounded and prisoners taken from the participating armies. The stories of what happened to the wounded survivors and prisoners is largely neglected. However, many petitions from Civil War soldiers provide detailed accounts of the ordeals that they went through following the fighting. Andrew Hopper uses documents from the battle of Seacroft Moor to fill in the gaps and argues that the aftermath of battles should hold as central a place in military studies as the events of those encounters themselves. On an unseasonably hot day on 30 March 1643, Sir Thomas Fairfax’s rearguard of three troops of horse and 700 foot were protecting the retreat of Lord Ferdinando Fairfax’s northern parliamentarian army from Selby to Leeds. Sir Thomas later reflected in his Short Memorials that when his infantry reached some enclosures on the edge of Seacroft Moor, ‘thinking themselves more secure’ from the feared royalist cavalry, they became ‘careless in keeping order’ and went into several houses seeking drinks. This allowed their royalist pursuers to catch up. Crossing the moor soon after, they were struck by twenty troops of royalist cavalry under Sir George Goring. Badly outnumbered and lacking pikes, many of Fairfax’s infantry were clubmen, volunteers armed with improvised weapons like scythes laid on poles. They cast down their arms and fled. Some were struck down and most were captured. Ensign John Hodgson, serving in Captain Nathaniel Bower’s company from Bradford later recalled: ‘I was there sore wounded, shot in two places, cut in several, and led off into a wood by one of my soldiers called Killinghall wood. With much ado he got me to Leeds in the night and it was a considerable time before I was cured.’ Hodgson was one of the lucky ones. Of the 700 foot, the Halifax apothecary John Brearcliffe recorded that 688 had been taken prisoner. Many of them were wounded like Hodgson with pistol balls and sword cuts but they were escorted under guard to the royalist northern headquarters in the city of York. Some were imprisoned in York Castle but others were held in Davy Hall and the medieval Merchant Taylors’ Hall (pictured here in its seventeenth-century brick cladding). Soon after, Lord Fairfax printed an accusation against the royalist general, the earl of Newcastle, of mistreating the Seacroft prisoners. He claimed that 100 were already dead and that 200 more lay sick and dying, having been denied provisions and medical treatment. Newcastle published a furious response, entitled The answer of His Excellency the Earle of Newcastle, to a late declaration of the Lord Fairefax. In it he declared that the prisoners had been visited by the Queen’s own physicians and that their wounds ‘had been dressed and cured by our surgeons at our charges’. Far from seeking the prisoners’ destruction, Newcastle maintained that he had permitted charitable collections for the prisoners and visits from their female relatives. Instead, Newcastle blamed Fairfax for the deaths in his custody that did occur, decrying him for having led them into rebellion and then for refusing fair treaties from Newcastle for their exchange. Newcastle added that Fairfax’s army was in rebellion and therefore illegal. That made Fairfax incapable of treating, he declared: ‘neither hee nor any of his pretended Captains in this Warr, can challenge any Interest in the Law of Arms’. Whatever the truth of the circumstances of their incarceration, one survivor, Joseph Bannister, a Halifax locksmith captured at Seacroft Moor, later testified that he had almost starved to death during his nineteen-week confinement in York and that many of his comrades died ‘from hard usage in prison’. On 27 June 1643, the Parliament Scout newsbook claimed that over 80 had died ‘from hard usage’. Writing around twenty years later, in his post-Restoration Short Memorials, Sir Thomas Fairfax remembered the plight of these prisoners: ‘Most of them being Country men, whose wives & Children were still Importunate for their Release, & which was as earnestly endeavored by us, but no Conditions would be accepted; so as their Continuall Cryes & Teares & Importunitys compelled us to thinke of some way to Redeeme these men, so as, we thought of Attempting Wakefield’. So on 20 May 1643, Sir Thomas Fairfax launched a surprise assault that defeated a major royalist force quartered in Wakefield, capturing Sir George Goring (son of George, Lord Goring of Hurstpierpoint), 38 officers and 1500 men. The West Riding parliamentarians were saved from despair and the prisoners from Seacroft could now be redeemed. Newcastle was quick to accuse Fairfax of maltreating them and intending to choke these prisoners ‘with the fumes of their own ordure, and to bury them alive in subterraneous Cellars where they cannot behold the light of Heaven but through a little grate of two spans breadth’. Now it was the turn of Lord Goring to be frightened. He wrote to Lord Fairfax pleading for the exchange of ‘my unfortunate sick sonne’, well knowing that Fairfax blamed him for the death of the Seacroft prisoners, and that his son had betrayed Parliament’s trust by changing sides in August 1642, making his trial by martial law a possibility. This episode encapsulates how the treatment of the wounded and the welfare of prisoners could so easily be turned towards propaganda purposes in the rival declarations issued by both sides. It also reminds us that the wounded and those taken captive should not be considered tangential to military studies as soon as they ceased to be combatants. The plight of the wounded prisoners of Seacroft, languishing in the Merchant Taylors’ Hall, in many ways continued to shape the strategy of generals and subsequent military events.

Read More

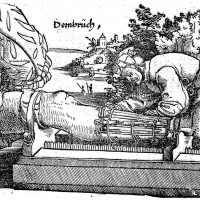

Straight from the Horse-Owner’s Mouth: George Rolph and the Fate of Civil War Wagoners

Maimed soldiers and soldiers’ widows were not the only people whose lives were ruined by the civil wars. Many more people suffered material losses or had their worlds turned upside down. They too petitioned for redress for a wide range of calamities. Unfortunately, due to time restraints, Civil War petitions will not be able to include these additional cases within the main project but we hope to draw attention to them via the blog. Here, in our first guest blog, Dr Gavin Robinson, examines the fate of horses and their owners impressed into Civil War armies. George Rolph or Rolfe was a wagoner from Latton in Essex (this could be Latton, now in Harlow, or Leyton, now in London). He petitioned the Essex Quarter Sessions in January 1658 that ‘his Waggon & horses were some yeares since impressed for the carryeing Ammuicon from London towards the releife of Glocester then besieged, and soe continued in the Parliments service until the Wagon was broken & horses killed at Newbury fight, for which the Peticoner had noe satisfacon and whereby hee is brought into Poverty’. He was granted a one-off payment of £10, but petitioned again in October. He was then given another £10, ‘Provided he never after trouble the Court wth any further Complaint therein, as hee now promiseth’. The relief of Gloucester and first battle of Newbury happened in September 1643, so Rolfe had waited 15 years for compensation. He may have tried and failed to get money from other sources, but no records of that have turned up. £20 is a large sum, but it was not necessarily generous considering the scale of Rolfe’s losses. Civil War armies paid up to £6 for draught horses, and there could often be five or six horses in a team. The Eastern Association paid £7.10s for an ammunition wagon in 1644. The capital needed to set up in businesses means that wagoners were probably middling entrepreneurs, but Rolfe’s case shows that they could easily be ruined if they lost their horses. During the Civil Wars, the risk of losing horses increased because armies needed so many of them. The planned establishment for the New Model Army’s artillery train included 32 artillery pieces, 132 wagons and carts, and over 1,000 draught horses (TNA, SP 28/145, ff. 60-64). The earl of Essex’s train had been a similar size. In May 1644, its accounts (TNA, SP 28/146, f. 183) show that it had: 613 state-owned horses 179 horses hired from contractors 50 teams of horses temporarily impressed Essex’s artillery never had enough state horses, so they relied on hiring and impressment to make up the deficit. For armies, the main advantage of impressment was that it was cheap, but it was not always efficient. A shortage of horses could help to explain why Essex’s artillery train was notoriously slow before the battle of Edgehill. Letters from royalist commanders sometimes mention that they could not get enough horses to move their artillery or ammunition. Whenever royalist commissaries took up large numbers of horses and wagons, it gave parliamentarian scouts a clue that the enemy army was about to move. To avoid these problems, the New Model Army was intended to have enough draught horses of its own but impressment was still needed sometimes. Sir Thomas Fairfax impressed teams of horses from Old Milverton, Warwickshire, in June 1645 to carry ammunition (TNA, SP 28/183). Humphrey Lower, keeper of the Army's stores at Reading, paid for sending warrants to local constables to impress carts. Although the carters were paid sixpence per mile, they were not willing volunteers. Lower also had to pay, ‘to Guard the 3 Gates at Redding to keepe these Carts that they might not goe thence, as some of them indeavoured’ (TNA, SP 28/202, f. 234r). Impressment was an even bigger problem for civilians than for armies. George Rolfe’s case is not very unusual. Although impressment was usually temporary, the risk of horses being killed or captured by the enemy was much higher when serving with an army. Even if the horses returned safely, their owners still suffered inconvenience and loss of earnings. Parish accounts of losses are full of claims for cart service and losses of horses. Buckinghamshire suffered very badly because it was where the relief force for Gloucester gathered before setting off in late August 1643. We don’t know where George Rolfe’s horses were impressed. Wagoners had to travel to carry out their business. Robert Bennett, a wagoner from Exeter, took a load of cloth from Devon to London, where he, his wagon, and seven horses were impressed into the earl of Essex’s artillery train in September 1642. They served until 23 October, when the wagon and horses were lost at the battle of Edgehill. Bennett’s petition to the earl of Essex resulted in £82 compensation. It’s not clear why George Rolfe didn’t get his money this way. Once horses were impressed into an army, there were many things that could go wrong. George Rolfe’s horses were killed in a battle, but accidents could happen even when there were no enemies around. Henry Foster’s narrative of the relief of Gloucester says that when the column was at the top of Prestbury Hill, near Cheltenham, on the evening of 5 September 1643: ‘it began to be very darke, so that our waggons and carriages could not get downe the hill, many of them were overthrowne and broken, it being a very craggy steep and dangerous hill, so that the rest of the waggons durst not adventure to goe downe, but stayed all night there: sixe or seven horses lay dead there the next morning, that were killed by the overthrow of the waggons’ In 1644, Essex’s army took horses from Buckinghamshire all the way to Cornwall, where they were lost. The surviving parish accounts for Buckinghamshire, which cover just over a third of the county, claim that during the First Civil War, 81 impressed draught horses never came back. Impressment put the wagoners themselves at risk, because someone had to drive the wagon and look after the horses. They suffered badly when Prince Rupert’s cavalry attacked the parliamentarian baggage at the battle of Edgehill. John Padgitt claimed to have suffered two wounds as well as losing a wagon, three horses and harness worth £23. Thomas Padgitt was also wounded and his son was killed, on top of £27 of losses in horses and harness. Together with John Wilde, they petitioned the Committee of Safety and were paid £75.10s between them (TNA, SP 28/6/2, f. 255; SP 28/263, ff. 23-24). Will the project find any more petitions from maimed wagoners? Dr Gavin Robinson is an independent researcher. He has published articles and a book on horses in the English Civil War. He also runs his own business, doing manuscript transcription and data cleaning for historians.

Read More

‘Wounded att Stampford Worke’: Two Devon ‘Tinners’ Recall their Wartime Service

The horrors of war are known to forge strong bonds of friendship and reinforce existing ones; friendships that do not end once the fighting is over. Here, Mark Stoyle examines the petitions of two men recruited from the same Devon parish and who served in the same regiment, revealing that their recollections of royalist service reveal strikingly significant similarities... After the Restoration, two former Royalist soldiers from the remote Dartmoor parish of Lustleigh petitioned the Devon JPs for pensions to support them in their declining years, both men testifying that they had been wounded in Charles I’s service during the Civil War. The first petition was that of Laurence Elliott, whose occupation was left unspecified, the second that of Robert Spray, a husbandman. Although the petitions are in different hands, there are hints that there may have been personal or textual interconnections between the scribes who penned them as both petitions refer to their subjects being now grow ‘old … and decrepped’: a slightly unusual formulation. The stories which the two documents tell possess a number of striking parallels, moreover. Thus Elliott’s petition states that he had served in the king’s western army ‘under the commaund of Bartholomew Gidley, Esquire, Captain of the Tinners’, while Spray’s petition states - rather more expansively - that he had served ‘under … Bartholomew Gidley, Esquire, Captain under the command of Sir Nicholas Slanning, K[nigh]t, Colonell of the Tinners’. Slanning and Gidley were names to conjure with in post-Restoration Devon. Sir Nicholas Slanning had been the original commander of one of the five ‘Old Cornish’ regiments which had conquered South West England for the king during the summer of 1643: a regiment which had been largely recruited from among the ‘Tinners’, or tin-miners, of Devon and Cornwall. In July 1643 Slanning had been mortally wounded at the storm of Bristol. Sixty years later, his name - together with those of other key officers who had died in the king’s service in the West - was still remembered by local loyalists in the mournful distich: ‘[Gone] the four wheels of Charles’s Wain: Grenville, Godolphin, Trevanion, Slanning slain’. The phrasing of Spray’s petition strongly suggests that he had served under Slanning’s personal command - but it is also conceivable that he had joined the Tinners regiment after the death of its most famous colonel, and that he and/or the scribe who drew up his petition had subsequently taken the tactical decision to include Slanning’s name in the document in order to furnish it with added lustre. What is crystal clear is that both Elliott and Spray had served in the company of Captain Bartholomew Gidley, of Winkleigh: a Royalist gentleman who had fought with distinction in the Tinners regiment throughout the war and who had been appointed to the Devon Bench after the Restoration. Indeed, Gidley himself was one of the four JPs who appended their signatures at the bottom of Elliott’s petition and affirmed that they believed its contents to be true: striking evidence of the fact that the bonds between some former Royalist officers and their soldiers had continued to endure long after the Civil War was over. That Elliott and Spray later testified that they had served under the same company commander in the same regiment strongly suggests that the two men had joined up at the same time, and it is fascinating to note that their petitions also show that they had gone on to be wounded in the very same engagement: the assault on the Parliamentarian fort of Mount Stamford, near Plymouth, in late 1643. Following the Royalist capture of Bristol that summer - an event which had seemed, to many, to herald the imminent collapse of the Parliamentarian cause - the king’s western army had marched back to Devon in order to reduce the remaining Roundhead strongholds there. Exeter was taken on 7 September and Dartmouth a month later, and by mid-October the king’s victorious forces were closing in on Plymouth: by now the only place in Devon and Cornwall which continued to hold out for the Parliament. Having surveyed the town’s defences, the Royalists quickly decided that Mount Stamford - an isolated earthwork fort which the Parliamentarians had thrown up on a peninsula on the other side of the Catwater, and which was thought to command Plymouth Sound - was the key to the entire position. Accordingly, they made their dispositions and prepared to move into the attack. On 21 October the Royalists began to erect earthworks of their own to the south of Mount Stamford, and over the following days a series of bitter skirmishes took place as the defenders tried to drive them off. It was not long before the Cavaliers were ready to launch their final assault. ‘The 5 of November, in the morning betimes’, wrote an anonymous Royalist eyewitness, who later composed a vivid account of events, ‘our ordenance begone to play upon Mount Stamfort’. The barrage continued all that day and the next morning, he went on and ‘all this whille wee stod in redinesse to fall on … being 3 regiments of foote and 5 trupes of horse’. Neither the eyewitness nor any other contemporary source names the three Royalist infantry regiments which took part in the assault, but the petitions of Elliott and Spray make it clear that the Tinners regiment was one of them. ‘The word beeing given, which was “victory”’, the eyewitness goes on, then ‘our foote marchet up [to the enemy work] … when, beeing together, wee made 3 shouts which made the hilles ring’. The Royalist forces now moved into the assault, and, after a hard-fought struggle, finally captured Mount Stamford. Among the many soldiers injured in the fighting that day were Laurence Elliott, whose petition attests that he was ‘wounded … att Stampford worke against Plimmouth’ and Robert Spray, whose petition likewise sorrowfully records that he ‘tooke great hurt … at the takeinge of Stampford worke against Plimouth’. The fact that two men from Lustleigh - a little moorland parish whose entire adult male population in 1641-42 was only around 50 - can be shown to have been wounded in the same engagement is revealing. It reminds us that, because the regiments of the Civil War tended to be raised - initially at least - from quite tightly-contained geographic areas, it was possible for individual parishes to suffer very high casualty rates when ‘their’ regiments took part in especially bloody actions. The parallel journeys which Elliott and Spray made - from the peace of Lustleigh to the hell of the siege of Plymouth and back - also makes us curious about their own relationship. One cannot help wondering whether the two men were friends and whether they continued to meet up to discuss their wartime experiences long after the conflict was over - just as we know that the men of the nearby parish of Drewsteignton were to continue to meet up to discuss their wartime experiences in the local pub in the wake of another, still greater conflict, three centuries later. A final question raised by these intriguing twin petitions is why the only wartime engagement which either of them mentions by name is the fight at Mount Stamford - even though Spray’s petition proudly declare that he had fought ‘in many battles’ on the king’s behalf? An obvious answer would be to suggest that both men’s military careers had been terminated by the wounds they received in November 1643, and that this in turn meant that the fight at Mount Stamford was the obvious ‘peg’ on which to hang their petitions. Matters are not so clear-cut, however, for, in point of fact, both men’s testimonies affirm that they had served throughout the conflict: ‘from the beginninge to the end of the said warr’ in Elliott’s case, and ‘to the end of the said warrs’ in Spray’s. The Civil War in Devon did not end until 1646, so - unless we presume that the petitions claimed that Elliott and Spray had fought throughout the entire war as a simple matter of form, as a method of putting their loyalty beyond doubt - there must have been another reason for the petitioners themselves, or for the scribes who wrote on their behalf, or both, to have laid particular emphasis on the fact that the former soldiers’ wounds had been received at Mount Stamford. It is important to remember here, perhaps, that in November 1643, the Royalists had celebrated their successful assault on Mount Stamford as a glorious feat of arms: as a victory which would lead, ineluctably, to the surrender of Plymouth itself, and which would thus permit the remarkable string of victories which the king’s western army had achieved over the preceding six months to be crowned with final, definitive, triumph. Yet, in the end the Cavaliers were to be sorely disappointed. Cannon placed at Mount Stamford, it transpired, were unable to prevent Parliamentarian ships from entering Plymouth Sound and supplying the garrison with ammunition and food. As November passed away into December, moreover, the Royalist besiegers suffered increasingly heavy casualties as they strove, ineffectually, to breach the defences of the town itself. On Christmas Day 1643, the siege was lifted, and although the Royalists made many more attempts to capture Plymouth over the following two years they were invariably repulsed with heavy losses. The Tinners regiment - including Captain Gidley’s company - is known to have taken part in a number of these fruitless operations, so it seems probable that Laurence Elliott and Robert Spray did so, too. Yet it is easy to understand why - when the two old soldiers and their local backers were pondering how best to ‘spin’ their petitions to loyalist magistrates after 1660 - they might well have decided that it would be more politic to highlight the injuries which the men had received during the brief moment of Royalist triumph before Plymouth in November 1643 than to itemise any further ‘hurts’ they may have suffered during the long, sad series of reverses before the same town which followed. Civil War petitions like the two discussed above not only provide us with vivid insights into the lived experience of the conflict itself, in other words, they also provide us with tantalising hints of the myriad ways in which individuals’ memories of that conflict could be subsequently sorted, sifted and deployed - both consciously and sub-consciously - in support of their own present purposes.

Read More

Uncertain Authors: Who Wrote Civil War Petitions?

Among the most attractive elements of petitions from veterans and widows of the Civil Wars are their vivid personal narratives. The documents are full of drama, pathos and suffering. Terrible injuries are narrated, litanies of military service rehearsed, and vivid accounts of desperate personal circumstances given. These petitions provide a unique opportunity to learn more about the experiences of thousands of humble individuals during the tumultuous seventeenth century; individuals who have often left little or no other mark in the historical record. And yet we must be careful in thinking that these documents allow us some kind of unfettered access to the ‘real’ experiences of the personalities under whose names they were presented. In this blog, Lloyd Bowen considers the problem of authorship in Civil War Petitions. Petitions to justices of the peace had a long pedigree by the 1640s. They thus also had an established form and a set of conventions which needed to be observed to be successful. The mode of address needed to be humble, even obsequious. Fulsome declarations of loyalty (to parliament, and, after May 1660, to the restored monarchy) needed to be made. The petitioner requested their due under the law but could be in trouble if they articulated this too forcefully and demanded money and support as their right. As a result, petitions often followed something of a script. They were accounts of individual experiences, but these experiences were moulded to meet expectations of the genre. The ‘authentic voice’ of the petitioner is further called into question when we remember that many of those petitioning for relief from magistrates, monarch, parliament or military commanders were illiterate and incapable of producing the documents themselves. Many petitions were drawn up (perhaps even composed) on the petitioner’s behalf by literate individuals. The person who put pen to paper, then, might be a scrivener or a clerk who probably charged a fee. It may equally have been a literate neighbour such as a local church minister or schoolmaster. Thus, many of these documents are well-written in a neat scribal hand and follow a distinctive visual and textual format. The vast majority do not possess the signature of the ‘petitioner’ or any other textual mark indicating his or her physical interaction with the document. When such signatures are found on petitions, they are usually from members of the officer class rather than the ordinary ranks. The authorial distance between petitioner and petition is often underlined by the fact that they were written in the third person. Individuals are described as ‘your petitioner’, and the pronouns ‘he’ and ‘she’ are standard forms of self-address. However, there are fascinating instances when such standard formats were not followed. Many individuals below the elite were able to write and some composed their own petitions. These can sometimes be distinguished by non-scribal, often messy, handwriting, and the presence of heavily phonetic spelling. The 1648 petition of John ap Rice and his brother Evan to the parliamentarian commander Sir Thomas Myddleton, for example, addresses the latter as the ‘right onorabell Sir Thomas’, and is suggestive of self-authorship by working through the plural first person: ‘wee being well affected to this sidde [side]’. Another example is the 1643/4 petition of Corporal John Barrett to Edward Massey, governor of Gloucester. Apparently written by Barrett himself, the petition deviates from the formal mode of the genre when relating the injuries he sustained in a skirmish near Painswick. Its language is familiar, almost intimate, when discussing his ‘7 wounds in the head; 5 of them therow the scull i cut in the backe (to the bons) with a pole axe; his elbow cut off bons and all: his hand slitt downe betwine the fingers as Mr Caradine the cyerrugion [surgeon] afermeth, who hath almost cured them al (and very carfuly and willingly he hath taken the pains to do it). How to satisfie him we know not; he was never the man that asked us a farthing’. Another intriguing example is the petition of Elizabeth Newam of Nottinghamshire. She approached the local parliamentary committee for assistance in December 1645 following her husband’s death in service. Her petition was written in a legible but not professional hand, while the spelling suggests an educated, but not trained, scribe. It articulated Elizabeth’s troubles in the first person throughout, suggesting a rare example of a female-authored text: ‘I not knowing without your honours commiseration how to subsist unless I bee forct to sell up all that I have, and soe I and my poor infant shall bee forced to beg, wheirfor I humbley intreat your honours compassion’. But even here it seems we should be cautious of ascribing ‘authorship’ too readily. At the bottom of the petition is a note in an altogether more flowing and practised hand recording the receipt of five shillings as well as ‘Elizabeth Newams marke’. Newam could not sign her name. The ‘I’s of her petition were laid down by a pen other than her own. Other instances when the veil of authorship slips and we glimpse the individuals behind petitionary narratives survive among the material from the north Wales county of Denbighshire. Thomas Lloyd of Llanrhyader, a pressed soldier who served in the king’s armies for five years before being wounded, petitioned the county sessions in October 1667 requesting payment of a pension awarded in an earlier session but yet to be fulfilled. When discussing the commanders who had previously attested to his service, his petition reads that these men were ‘certifieinge my loyaltie’, which has been changed to the expected form of ‘his loyaltie’. Interestingly, this petition also has a rather idiosyncratic register in parts, suggesting that Lloyd’s authorship of this document was more fully present than was often the case. Similarly, the petition presented to the Denbighshire justices by Reece Ithel of Holt at the January 1668 sessions hints at the composition process behind many of these documents. Ithel’s petition informed the justices about his service as a soldier ‘dureing all the time for most of the late unhappy warrs’, in which he had been wounded, thrice imprisoned, had his house burned, and his good stolen. The petition’s public face then slips. It lapses into the first person: ‘I was very poore & hath soe continued ever since and still am’. The text has been amended before presentation to the magistrates, however, to read ‘hee was very poore … & still is’. Similar transformations are found elsewhere; in one instance the word ‘myselfe’ as been transformed into ‘himselfe’, with the tell-tale descender of the ‘y’ pendulous and incongruous under the revised word. These shifts in the authorial voice can be found in other parts of the country too. In Essex, for example, the 1653 petition of Martha Emming, a widow of Coggeshall, begins by relating to the justices how ‘yor peticoners husband and two of her sons’ enlisted for the parliamentary army. However, when discussing her husband’s death at York in 1644, the document moves into a mixture of the first and third person. Emming recalled how ‘at the seedg [siege] … it pleaseth god to take away the life of my said husband and soone after him one of my sonnes in Ireland to the great greeife and also to the hinderance of your poore peticioner’. The terrible trauma she had suffered bleeds through the text, providing a more immediate authorial presence than the usual remove of petitionary propriety. The interpolation of the present tense into this traumatic memory adds to the awkward mixture of raw emotion and generic distance. It is not clear that Lloyd, Ithel or Emming personally wrote their petitions. The confused pronouns may well have been the work of scribes who were themselves inexpert in the business of formulating a petition for the bench. Equally, it may just have been a scrivener whose mind wandered during the process of transcribing after a jug or two of ale. These slips and shifts, however, are testimony to the constructed nature of these petitions and the several hands involved in their making. They remind us that while these documents bring us as close as any to the individual experience of Civil War at the level of the ordinary solider or widow, they remain far from the unmediated testimony of individual experience.

Read More

The Dogged Determination of William Gray of Braintree, Essex

Among other things, the material gathered by our project will give historians valuable insights into the ways in which ordinary people negotiated with their rulers. We’ve been struck by the clever strategies adopted by many petitioners, their assertiveness in the face of authority, and their dogged determination to obtain justice. Here, David Appleby takes up the story of a serial petitioner from Essex – a maimed soldier who refused to be silenced, and eventually got his reward. Before the outbreak of civil war, William Gray was a family man with a good trade and decent prospects. He was a woolcomber, a skilled occupation whose practitioners tended to be members of the respectable ‘middling sort’. Gray’s home town of Braintree, whose cloth was exported all over Europe, was a hotbed of puritanism. When war became inevitable, thousands of Essex men came forward to volunteer for Parliament’s armies. It is evident that Gray was among them. He served as a private soldier in the earl of Essex’s army, fought at the siege of Reading in April 1643, and in the subsequent campaign. His company commander, William Jarman, attested that Gray was an orderly and sober man. The Essex justices would later record that he was ‘many years’ in the army. The fact that Gray had acquired extensive military experience and was of good character was clearly influential in his appointment as a sergeant in Colonel Thomas Cooke’s regiment during the Second Civil War of 1648. Cooke had hastily assembled his auxiliaries as the royalist insurrection in Kent spilled over into Essex. Gray was posted to the colonel’s own company, perhaps on the recommendation of William Jarman, who had been appointed major in the same unit. The regiment saw hard service at the siege of Colchester in 1648, and later at the battle of Worcester in the Third Civil War of 1650-1. It was during one of these campaigns that Gray was so badly wounded as to prevent him from resuming his peacetime occupation. Far from being a man with prospects, he and his family now faced a lifetime of poverty. Gray does not appear in the Essex quarter sessions records until 1657. Like so many maimed soldiers and war widows, he may initially have tried to struggle on without charity. He obtained a certificate from William Jarman in January 1657, and armed with this testament of his loyal service to Parliament, petitioned the Essex justices for a pension. He received only a one-off gratuity of 40 shillings. Undeterred – or desperate – Gray submitted another petition for the April quarter sessions. The justices were even less sympathetic; nevertheless, they conceded that he had received ‘some wounds’, and ‘to prevent further trouble with him’, ordered the Treasurer for Maimed Soldiers to pay him a gratuity of 20 shillings. The former sergeant immediately tried a different tactic, obtaining a medical report from a barber surgeon named Thomas Cosin. Cosin’s detailed diagnosis illustrated the extent of Gray’s debilitating injuries, particularly emphasising that his leg had ‘been broken in many pieces, which hath occasioned a great imbecility’. Nevertheless, at the Midsummer sessions of July 1657, the justices were clearly irritated that Gray had had the temerity to present his case to them yet again. They grudgingly ordered the Treasurer for the East Division to pay him a final gratuity of 20 shillings, adding that ‘[we] do require the said Gray never hereafter to trouble the Sessions for any further relief’. Such official rebukes – which can be seen in the records of many counties – deterred many maimed soldiers and war widows from continuing to press their claim. However, William Gray was made of sterner stuff. He boldly appeared at the next quarter sessions in October 1657, and petitioned yet again. The exasperated justices accepted defeat and ordered that Gray henceforth receive a pension of 40 shillings per year. This was not much, given that he had to support a whole family, but it does at least prove that his persistence was ultimately effective.

Read More

Meet a Petitioner – John Melmerby of Brompton-on-Swale, North Riding of Yorkshire

So what were the men and women who petitioned for financial relief during and after the Civil Wars like? Naturally they were a mixed bunch, but their interactions with the authorities sometimes reveal surprising stories. Here, in a tale of crime, punishment and derring-do, Andrew Hopper tells the tale of John Melmerby. John Melmerby of Brompton-on-Swale, near Richmond in the North Riding of Yorkshire, was a maimed soldier who served in parliament’s army. He was awarded a pension of £4 per year at the Thirsk quarter sessions in April 1652. Despite the Restoration of Charles II, he was still receiving this pension in October 1661, although it was probably withdrawn soon after. In July 1674, the Northallerton sessions declared him ‘a vagabond and an incorrigible rogue’ for stealing one cock and three hens worth 2 shillings and 6 pence. He was ordered to be whipped and burnt in the left shoulder. He was thrown into prison at York Castle to await transportation to English plantations overseas. Soon after, he ‘feloniously made his escape’ because in January 1675 the Richmond sessions ordered Katherine Hall to be imprisoned in York Castle for harbouring him. In July 1675, he was again presented before the quarter sessions for stealing three bushels of rye worth 6 shillings. In October 1680 the treasurer for maimed soldiers was ordered to pay Jasper Yates 40 shillings for prosecuting the king’s evidence against Melmerby at the York assizes. The following July, Samuel Rawling of Catterick was awarded 6 shillings 8 pence for having prosecuted Melmerby for felony before Melmerby's final execution at the York assizes.