HIGHLY COMMENDED IN THE BRITISH RECORDS ASSOCIATION’S JANETTE HARLEY PRIZE 2020:

https://www.britishrecordsassociation.org.uk/press-release-winner-of-the-2020-janette-harley-prize-announced/

Echoes of a Massacre: The Petition of Bridget Rumney

The massacre of the royalist camp-followers in Farndon Field following the battle of Naseby was one of the most notorious incidents in the English Civil Wars and a subject of intense debate since. At the heart of this debate lies an uncertainty as to the identity of the unfortunate victims. However, in this week's blog, Mark Stoyle reveals the identity of one family group present on that fateful day. This discovery has been made possible by a petition addressed to Charles II in May 1660, the contents of which remind us that women and children could be as much at risk from the dangers of war as the combatants who fought in the conflict. On 14 June 1645, parliament’s New Model Army, under the command of Sir Thomas Fairfax, Oliver Cromwell and Philip Skippon, utterly defeated Charles I’s main field army at the battle of Naseby. As every history of the Civil War attests, it was a decisive engagement: one which resulted in the destruction of the king’s veteran infantry force, the flight of his cavalry and the capture of his baggage-train, together with all of his personal correspondence. What is too often forgotten is that the battle of Naseby also resulted in perhaps the single worst atrocity of the Civil War in England, for, as the victorious Parliamentarian soldiers pursued their beaten enemies from the field, they fell upon the king’s female camp-followers, who, having seen that the day was lost, had set off in headlong flight towards the royalist garrison at Leicester. According to a later account, the parliamentarian troopers caught up with the terrified fugitives ‘in the south part of Farndon-field, within the gate place in the road between Naseby and Farndon’. Here a dreadful slaughter ensued, as the soldiers set about the Royalist women with their swords, killing at least a hundred of them, and savagely mutilating many more. In the aftermath of the battle, parliamentarian pamphleteers in London made no apology for what their soldiers had done, but rather triumphed in their murderous actions: some claiming that the killed and injured women had been ‘whores’, others that they had been Irish women, ‘wives of the bloody rebells in Ireland’, who had - according to earlier, exaggerated, accounts - slain thousands of Protestant men and women during the Irish Rebellion of 1641. The reports which appeared in the London press in the immediate aftermath of the battle are the chief surviving sources for the acts of butchery which were perpetrated in Farndon Field and, as a result, it is through the lens of these - highly partisan - reports that the victims of the massacre have tended to be viewed ever since. That many of the parliamentarian soldiers who took part in the attack genuinely believed the women who accompanied the royalist army to be a horde of sexually immoral ‘courtesans’, interspersed with companies of knife-wielding ‘Irish-sluts’ and even the occasional ‘witch’, is easy to credit; this was, after all, what their own propagandists in London had been affirming in print almost from the moment that the conflict began. Yet, clearly, we cannot assume that such tendentious reports painted a wholly accurate picture of the women who marched in the king’s train - while the fact that one of the few royalist sources to allude to the massacre describes those who were killed as ‘women and soldiers’ wives’ strongly suggests that, while some of the luckless individuals who were cut down by the Parliamentarian troopers may, indeed, have been ‘common women’, or prostitutes, many entirely ‘respectable’ women were slaughtered as well. Little evidence has survived about the individual women who suffered at Naseby, though we do catch just an occasional glimpse of them in the historical record. On 1 July 1645, for example, the parish clerk of Kidderminster, near Worcester, recorded the burial of ‘a woman … wounded at the battle in Leicestershire’. Almost certainly, this was one of the king’s camp-followers who had been injured at Naseby, but who had nevertheless managed to escape from the battlefield and to flee towards the West alongside the rest of the broken royalist forces, only to die - whether of her wounds, of illness, or of simple exhaustion - a fortnight later. Yet, poignant as this brief record is, it tells us next to nothing about the flesh-and-blood woman for whom it now stands as the sole surviving epitaph. Altogether more revealing is a document preserved among the State Papers, which permits us to rescue one of the women who perished at Naseby from the anonymity which has cloaked the victims of the massacre hitherto - and, in the process, to subvert the London pamphleteers’ representation of them as a mere ‘rabble’ of violent and licentious individuals. In May 1660 a certain Bridget Rumney submitted a petition to the newly-restored King Charles II in which she begged that she herself might be ‘restowred’ to the position at Court which she had enjoyed during the reign of his father. Rumney began by explaining that she and her mother, Elizabeth Burgess, had long been members of the royal household, and, more specifically that they had ‘bin servants to your Gracious Majesty’s late Grandfather [i.e. James I and VI] and father [i.e. Charles I] … in the Office for providing of flowers and sweete herbes for the Court’. In proof of her claim that she had been appointed to this office - the chief duty of which was to strew sweet-smelling flowers and herbs around the royal lodgings - in succession to her mother, Rumney enclosed a certificate signed by one Peter Newton, a former household servant to Charles I. ‘These are to certifie’, Newton’s note ran: ‘that by virtue of a warrant to mee directed, from the kings … majesty, I have sworn the bearer hereof, Bridget Rumney, garnisher and trimmer of the [royal] Chapple, Presence and Privy Lodgings, in the roome of Elizabeth Burgess hir mother, deceased, to hould and enjoy the same with all fees and profits thereto belonging’. The fact that this certificate is dated 11 September 1647 makes it clear that Rumney had succeeded to her mother’s position at a time when Charles I had been living in distinctly reduced circumstances following his defeat in the Civil War: at his palace of Hampton Court, certainly, but by now in the custody of the victorious New Model Army. Within a year and a half of Rumney’s having been sworn in, the king had met his death upon the scaffold at Whitehall, so Bridget can have had little time to enjoy her new position. This misfortune was by no means the worst that Rumney had had to suffer in her life, however, for, as her post-war petition makes clear, she had only succeeded to her mother’s office in the first place as the result of a family tragedy. For ‘soe yt is’, she sorrowfully informed Charles II in 1660, ‘that your petitioner’s poor mother and two of your petitioner’s sons were slayne at Nazebie’. Rumney’s testimony is fascinating: first, because it permits us to identify Elizabeth Burgess as having been, almost certainly, one of the victims of the Naseby massacre, and second because it allows us to see that - far from having been one of ‘the harlots with golden tresses’ of the London pamphleteers’ fevered imaginations - this particular victim of the Parliamentarian soldiers’ rage had in fact been a domestic servant of relatively advanced years, whose chief occupation before the outbreak of the conflict had been the scattering of flowers and herbs around the royal court. Rumney’s bleak, matter-of-fact statement about the death of her mother and her two sons raises all sorts of unanswerable questions. What had Burgess been doing in the king’s train during the fateful summer of 1645, for example? Had she been continuing to carry out her pre-war duties at the peripatetic court which sprang up in the field wherever Charles I halted as he marched across the countryside on campaign? Or had she had been acting in some other domestic role in the royalist baggage-train, after having gravitated to the king’s army as a place of continued employment and refuge following Charles I’s enforced departure from his palace at Whitehall in 1642? Was Bridget Rumney with her mother on the day that the latter was killed? And what of Rumney’s two sons? Had they been young men serving in the Cavalier army? Or had they been mere boys, fleeing alongside their grandmother - and their mother, too, perhaps - as the troopers bore down on the terrified throng of civilians streaming along the road from Naseby to Farndon? We cannot know - although the fact that Rumney stated in her later petition that she had been left with ‘six smale children’ after her mother’s death hardly suggests that her two ‘slayne’ sons can have been very old. It is pleasant to be able to record that Rumney’s plea that her old office should be restored to her was granted by Charles II - and that she continued to serve as his official ‘Herb-woman’ throughout the 1660s, receiving the handsome salary of £24 per annum for her pains. The relief of securing a permanent post at court again, together with all of the financial and social benefits it brought, must surely have done something to assuage Rumney’s pain over the triple bereavement which she had suffered during the Civil War. It is hard to believe that she can ever have forgotten that conflict, though - or the terrible fate which had befallen her sons, her mother and so many other non-combatant women in the wake of what one contemporary writer aptly termed ‘the battle of Dreadful Down’. Suggestions for further reading: Glenn Foard, Naseby: The Decisive Campaign (Whitstable, 1995). Ann Hughes, Gender and the English Revolution (Abingdon, 2012). Mark Stoyle, ‘The Road to Farndon Field: Explaining the Massacre of the Royalist Women at Naseby’, The English Historical Review, volume 123 (August 2008), pp. 895-923.

Read More

Prisoners of war: the lowest priority

The plight and place in diplomatic relations of prisoners of war during the Civil Wars was discussed in a previous blog but how did the situation differ for the prisoners of war originating from foreign powers? During the Interregnum and Restoration periods at the heart of the chronological era under study by Civil War Petitions, Britain fought three wars against the Dutch Republic. These resulted in the capture of numerous sailors by both sides, who were then held as prisoners of war. We are delighted to welcome Gijs Rommelse, who in this guest blog reveals the concerns raised about the welfare of Dutch sailors incarcerated in England and the discrepancy between theory and reality in the treatment of foreign prisoners of war in England. In 1656, Arnoldus Montanus, a preacher of the Dutch Reformed Church, published in Amsterdam a pamphlet entitled The troubled ocean, or the two-year sea exploits of the united Dutch and the English. Montanus, who at Leiden had studied philosophy and theology, wrote copiously on these and also historical and geographical subjects, and was a fanatical supporter of the House of Orange. In his account of the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654), he wrote of Dutch prisoners of war, who in 1653 were incarcerated in Ipswich and Chelsea, and the appalling treatment to which they were subjected. ‘Those that death spared resembled skeletons rather than men … Some, from deprivation, lost their reason. In Chelsea they lay, under the open sky, within a walled enclosure with guards set round it. Those who, from despair, chose by escaping to risk an uncertain death, rather than a worse captivity, were often recaptured, shot, put to the sword, or at least to the torture.’ Montanus showed himself deeply troubled at the treatment received by the Dutch seamen in England, although his purple prose may also have served to increase the evocative power of his pamphlet. The question naturally arises as to the veracity of his account. He was certainly not the only Dutch writer to describe the captivity of prisoners of war in England as hellish. In 1667, an author, who preserved his anonymity by employing the initials EVL, published a pamphlet entitled The cautious Hollander. Shown in a dialogue between a politician, a merchant, a sea-captain. All three upright Hollanders. An Englishman, resident in Holland. He proposed that ‘Worse even than sudden death by water, fire, the sword or other deadly weapon is the frightful expiration from hunger, thirst, cold or other privation, to which one would not subject a dog. Nevertheless, in England our Dutch captives have met their deaths by all these cruel means, so that in places every tenth, ninth, eighth, seventh; yea, even every fourth or third man died or, more accurately, was driven to his death. This conduct is in flagrant contravention of the Rights of all Peoples and would not be possible without such violation.’ It is natural to question whether accounts such as the above reflect the bias of Dutch authors who, while they may well have believed in their own narratives, were prepared to pander to the strongly anti-British feelings of their intended reading public. This would be plausible, were it not for the fact that similar reports are to be found in English sources also. Andrew Marvell who, in his Character of Holland of 1672 had certainly shown himself no friend of the Dutch, wrote in 1677 that ‘Sir William Doyley got 7000 £. out of the Dutch prisoners’ allowance, and starved many of them to death.’ If Marvell, whose career was founded largely on biting criticism of others, may not have been the most reliable source, the same could certainly not be said of John Evelyn, the celebrated diarist who, like Doyley, was one the Commissioners for the Sick, Wounded and Prisoners. He wrote many letters to King Charles II and to various Privy Councilors with appeals for funds for the maintenance of the Dutch captives, who were accommodated at various locations. He pleaded the impossibility of the task of housing and feeding them in a humane manner. Their numbers were too great and they arrived, following the great sea battles, in unmanageable waves. So dire was their situation, he wrote, that they were held in the open air, without straw to lie on or sufficient food. Some had already died and others would soon follow if no funds could rapidly be made available. These representations he not only addressed to his superiors but also confided to his diary. There was, in the seventeenth century, as yet no legal code of practice concerning the treatment of prisoners of war. Usually, after some time had elapsed, the combatants would reach some ad hoc arrangement concerning the exchange of captives. It was not that no legal code of war existed; as noted above, for ‘EVL’ the English authorities were obliged to respect the Rights of all Peoples which, in principle, they observed: the Commonwealth, Protectorate and Restoration regimes had all felt themselves obliged to treat the Dutch prisoners humanely. They were, after all, fellow Christians fulfilling their obligation to serve their sovereign state. The unwritten convention obliged them to clothe, feed, house and care for their captives, who were not to be exposed to violent treatment. They were not to be denied the prospect of future freedom, either through a general exchange or the opportunity to purchase their release. The basis for this semi-official law of war was formed by Christian values and common humanity but also by calculated self-interest. The Dutch cities housed large numbers of English prisoners; reports of ill-treatment of Dutch captives in English hands could result in a cycle of reprisals (see photo above for an example of this). Since the English authorities apparently acknowledged their obligation under the informal rules of war to ensure that their Dutch captives were humanely treated, at the same time making reciprocal demands on the Republic regarding English captives held there, the question naturally arises why so many Dutch prisoners perished through starvation, disease and exhaustion? The answer lies in the simple fact that the needs of foreign prisoners occupied the lowest position on their captors’ list of priorities. Lack of money made it difficult for the English authorities always to maintain the navy’s ships in operational condition; failure to do so made it necessary to lay up the battle fleet in 1667, thereby making possible the Dutch Raid on the Medway. Since there was regularly insufficient money to pay the country’s own seamen, who were forced to accept promissory notes in the form of ‘tickets’, it is not surprising that for the Dutch prisoners there remained almost nothing for their needs. Since the English state finances proved incapable of meeting the challenges of intensive war making, relief attempts were made by Dutch diplomats, by Evelyn from his own pocket and by other English benefactors, but these could provide no more than a slight amelioration of the prisoners’ condition. Dr. Gijs Rommelse is an Honorary Visiting Fellow at the University of Leicester's School of History, Politics and International Relations. He teaches history and social sciences at the Haarlemmermeer Lyceum in Hoofddorp (The Netherlands) and is head of the school's History Department. Gijs gained his PhD from the University of Leiden with a dissertation titled 'The Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667)'. His research interests include Anglo-Dutch relations, early modern political and military cultures, privateering, prisoners of war and political economy. He has published widely on these subjects, his most recent work being (together with David Onnekink) The Dutch in the early modern world: A History of a Global Power (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Read More

What can I find on Civil War Petitions?

Since the official launch of Civil War Petitions in July, we have been working hard to gather new material. The research team have travelled to new archives and gathered data from new counties, whilst more records have been published and are ready to view on Civil War Petitions. Civil War Petitions now contains data from the following counties: Denbighshire (work in progress) Dorset (work in progress) Durham East Riding of Yorkshire (NEW) Essex Gloucestershire (work in progress) Hampshire Town and County of Kingston-upon-Hull Lincolnshire (work in progress) Town and County of Newcastle-upon-Tyne North Riding of Yorkshire (NEW) Northumberland Nottinghamshire (work in progress) West Riding of Yorkshire (work in progress) Worcestershire (NEW) City and County of York Of the new counties that have been published on Civil War Petitions and are now completed, the East Riding of Yorkshire has one order book containing payment records for the years 1647-51, the North Riding of Yorkshire has 23 petitions/certificates and a comprehensive series of 12 order books covering the period 1645-1710, whilst Worcestershire has ten petition/certificates, a set of treasurers’ accounts from 1655 and a handful of order book entries from 1661-63. Unfortunately, there was little relevant surviving material for either Berkshire or Bristol. We found a few payments amongst the county committee records for Berkshire, which we have uploaded to Civil War Petitions. For Bristol, there were voluminous records for the collection of the maimed soldiers’ tax but no petitions/certificates or records of payments – read about this in Mark Stoyle’s blog. Civil War Petitions remains a work in progress, but we have made steady progress on a number of other counties. We have published all the payment records from the order books and treasurers’ accounts for both Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire. We have published 17 of the 30 petitions surviving for Nottinghamshire. We hope to publish the remainder in the next few weeks, as well as the 11 surviving petitions for Lincolnshire. Work on the remainder of the detailed set of Dorset order books and treasurers’ accounts is likewise nearly finished, which will complete this county (unfortunately no petitions/certificates for Dorset). Significant inroads have been made into the voluminous records surviving for the West Riding of Yorkshire: the 106 petitions are steadily being published and 8 of the 13 order books are currently available. The completion of this county is our priority over the next few months, along with the publication of the 19 petitions/certificates for Gloucestershire, the 300 Denbighshire petitions/certificates and the exhaustive set of Denbighshire Treasurers’ Accounts. The counties which you can expect to see coming soon include: Caernarvonshire Derbyshire East Sussex Herefordshire Leicestershire and Rutland Northamptonshire Keep an eye on our Twitter feed and Facebook page for news of when these have been added For a full guide to the type of material that you will be able to find on Civil War Petitions, visit the About the Data page. For a full explanation of some of the terms used, visit the Glossary. In addition, we have made many improvements to the graphics and functionality on Civil War Petitions. We have a new and improved zoom function on the document images, whilst the website team have been developing customised maps to reflect the seventeenth-century topography. One version of these maps has been released on to the Historical Person pages to demonstrate a person’s place of residence, whilst further versions are currently being developed for the Locations and Events pages. The website team have also been working hard on improving the ways in which search results are displayed and on developing an advanced search function – more news on those functions shortly! Finally, we are working on ways to display summaries of all the statistics for each counties. It remains to be said that Civil War Petitions would not be possible without the help of a number of dedicated assistants. We are very grateful to our project volunteers who have helped us with the modernised transcriptions of the petitions and certificates. We would also like to thank all the staff of the various archives that we have visited for their time and patience, their enthusiasm for the project, and for arranging the digitisation of the documents for our images.

Read More

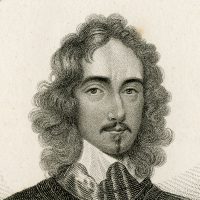

The War Hero, the Eccentric and the Turncoat: the Men Behind Three Signatures

Several of the signatories to the documents in our Civil War Petitions database will be familiar names to anyone interested in the period. In a previous blog, Andrew Hopper told the story of how Parliament’s Lord General, Thomas Fairfax intervened personally in two deserving cases in his native Yorkshire, writing in support of a widow from Leeds and a maimed veteran from Otley. Oliver Cromwell wrote numerous letters to request financial assistance for maimed parliamentarian veterans and war widows, in counties as far apart as Essex, Hampshire and Denbighshire. By contrast, the vast majority of local commanders and county officials whose signatures appear in the records are generally unknown to any except local historians. Nevertheless, these obscure characters are often interesting to research, and many turn out to have truly fascinating stories. Here, David Appleby reveals more information about three officials whose signatures appear repeatedly in the Nottinghamshire documents in our database: a war hero, an eccentric, and a turncoat. The War Hero: Francis Thornhagh of Fenton, Nottinghamshire (1617-1648). When Francis Thornhagh signed Francis Spry’s certificate in September 1646 fate would decree that the 29-year-old colonel had less than two years left to live. Lucy Hutchinson, the famous seventeenth-century writer, who rarely bestowed praise on anyone outside her immediate family, clearly held Thornhagh in high esteem. He was, she later recalled, ‘a man of a most upright faithfull heart to God and God’s people’, demonstrating ‘valour and noble daring’, and ‘of a most excellent good nature to all men.’ She could not resist adding that he was also often impulsive, and somewhat susceptible to flattery. At the same time, she conceded that he was always willing to admit to his shortcomings, and would never cling to a mistaken policy simply because he had instigated it. [Hutchinson Memoirs ed. Sutherland, pp. 72-3.] Thornhagh had been at school with Lucy’s husband, Colonel John Hutchinson, and proved a steadfast friend and ally throughout the latter’s governorship of Nottingham. He had previously served in the Dutch army, and so at the outbreak of hostilities Parliament commissioned him to raise a regiment of horse. Thornhagh proved to be a charismatic and competent leader. He served under Oliver Cromwell in Lincolnshire in 1643, and soon after took his regiment to join a taskforce being assembled by Sir John Meldrum to besiege Newark. In March 1644 Meldrum’s taskforce was surprised by Prince Rupert, and pinned against Newark’s defences. A Lincolnshire commander, Lord Willoughby panicked and fled, taking most of the parliamentarian cavalry with him. Thornhagh was made of sterner stuff: he rallied as many troopers as he could, and charged the royalist line. In the ensuing melee the outnumbered parliamentarians were decimated. Thornhagh was badly wounded, and carried back to Nottingham to die. However, confounding his surgeons, he recovered, and soon returned to active service. He fought at the battle of Rowton Heath in 1645, and took part in Sydenham Poyntz’s subsequent campaign in the East Midlands. Parliament commended him for his ‘many great and faithful services’ [Commons’ Journals, iv, p. 258]. When the Second Civil War broke out in 1648, Thornhagh again found himself under Oliver Cromwell’s command. At the battle of Preston in August his impetuosity finally proved his undoing: Cromwell reported that Thornhagh advanced too boldly, and was ‘run into the body and thigh and head by the Enemy’s lancers’. Thus the general was left to lament that a worthy gentleman ‘who often heretofore lost blood in your quarrel’ was dead. He reminded the Speaker of the Commons that Thornhagh had always been ‘faithful and gallant in your service as any’, and had left children ‘to inherit a Father’s honour, and a sad Widow – both now the interest of the Commonwealth’ [Carlyle, Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches, Vol I, part iv, letter xli, p. 284]. Yet another family had been bereaved by the Civil Wars. The eccentric: Clement Spelman of Narborough, Norfolk (1607-1679). Despite being a Norfolk gentleman, Clement Spelman became very influential in the parliamentarian administration in civil-war Nottinghamshire. His links with the Midlands seem to have stemmed from a family connection with the Willoughby family, who had extensive estates in Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. Spelman was clearly a conscientious and hardworking member of the Nottinghamshire county committee, for his signature appears a great many of the warrants to pay maimed soldiers and war widows. Interestingly, despite the fact that she must have known them, neither Spelman nor another industrious signatory, Nicholas Charlton receive a single mention in Lucy Hutchinson’s memoirs. Spelman was appointed deputy-recorder of Nottingham in 1647, and later rose to become Recorder and a magistrate of the Midland Circuit, apparently surviving the political purges which followed the Restoration. However, his main claim to fame lies not so much in his successful civic career, but in the manner of his entombment in Narborough parish church. It appears that the septuagenarian disliked the idea of being repeatedly walked over, and so left directions in his will that he should be buried standing up [Sherlock, Monuments and Memory in Early Modern England, p. 45]. According to the Victorian contractors who made some excavations in the church in the nineteenth century, this somewhat bizarre wish was carried out. He had been laid to rest (or more accurately stood to rest!) in 1679. The turncoat: Charles White of Newthorpe, Nottinghamshire (d. 1661) Whereas Lucy Hutchinson was generally positive in her assessment of Francis Thornhagh, she reserved some of the hottest bile in her memoirs for Charles White, a colleague of Thornhagh and Spelman on the Nottinghamshire committee. She described White as a social climber, a man of ‘mean birth and low fortunes’ who over the years had worked hard to ingratiate himself with the local gentry. ‘This man’, she wrote, had the most factious, ambitious, vainglorious, envious and malicious nature that is imaginable; but he was the greatest dissembler, flatterer, traitor and hypocrite that ever was.’ She accused him of feigning godliness and humility, whilst being a slave to alcohol and lust. By courting ‘the common people with all the plausibility and flattery that could be practised’, and by ostentatiously making large donations to fund godly preaching, Lucy asserted that White made himself popular and appeared a true advocate of the parliamentarian cause – until ‘he was discovered some years after’ [Hutchinson Memoirs ed. Sutherland, p. 69]. This was by any measure a damning excoriation, but recent research has found that Lucy Hutchinson tended to bend the truth when it suited her, particularly where her husband was concerned. She was obsessively protective of John Hutchinson’s memory, and it is very clear that he and Charles White were political enemies. Throughout the First Civil War their rival factions struggled for supremacy within the county committee. Worse still, it is obvious that Lucy, an avid supporter of the Commonwealth, was outraged by White’s eventual defection to the royalist cause. Nothing has as yet come to light in the archives to substantiate Lucy Hutchinson’s claims as to Charles White’s character. He appears to have been a socially conservative Presbyterian who served as an elder of the Nottinghamshire Classis, as did several other members of the Nottingham parliamentary county committee [University of Nottingham Special Collections, Nottingham Classis minute book, 1654-1660 Hi 2 M/1]. It is unsurprising that White and fellow conservatives would be opposed to the more radical group who followed Hutchinson. White saw his share of military action, serving as a captain of horse during Cromwell’s fight at Gainsborough in 1643, and commanding both dragoons and horse in the Nottingham garrison [Cromwell Association Online Directory of Parliamentarian Army Officers]. White’s gradual disillusionment with the direction of the revolutionary cause was typical of a great many Presbyterians. Some, such as Colonel Henry Farr (who will feature in a future blog) deprecated the incarceration of Charles I, and were alarmed by the rise of the radical Independents. As a result, Farr and others defected to the royalists at the start of the Second Civil War of 1648. Many more Presbyterians abandoned Parliament after the Regicide, shocked and appalled by the public execution of an anointed monarch. A final tranche of Presbyterians defected in 1659, anxious at the growing political chaos which had ensued after the eclipse of the Cromwellian Protectorate. Booth’s Rising in August 1659 was a coalition of royalists and Presbyterians: led in the north by the earl of Derby and Sir George Booth, and in the Midlands by Lord Richard Byron and Charles White (by now dubbed Colonel White), supported by former parliamentarians such as Colonel Edward Rossiter from Lincolnshire and Robert Pierrepoint, the son of a Nottinghamshire committee member. Just as Booth’s rising in the north was swiftly extinguished, so the attempted coup in the Midlands was soon put down. Byron had intended to seize the old royalist citadel of Newark, but he and White could only gather around 100 men, which was clearly insufficient to overpower the Commonwealth forces in the town. They headed instead for Nottingham, now closely pursued by militia cavalry. In a running series of skirmishes several hapless insurgents such as Peter Hodgson of Worksop, were wounded or captured. Charles White led a few of the survivors on to Derby, and actually succeeded in occupying the town for a few hours. However, he was soon forced to flee when regular troops from the New Model Army arrived in force. White remained on the run for several days, but was eventually captured. He was thrown into prison, and was lucky not to be executed. Charles White did not live long enough after the Restoration to be rewarded for his actions. The war hero, the eccentric and the (eventual) turncoat were clearly very different personalities, and typical of the different factions within the Nottinghamshire parliamentary county committee. That said, the fact these three men’s signatures often appear together on Nottinghamshire pay warrants indicates that these differences did not prevent them from cooperating in order to conduct routine business. This was obviously good news for maimed veterans and war widows who relied on them for financial support. Nottinghamshire recipients were luckier than their neighbours in Lincolnshire, where the county committee was so bitterly divided that it eventually ceased to function. Suggested reading: Thomas Carlyle (ed.), Oliver Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches (2 vols., New York: Wiley & Putham, 1845). Lucy Hutchinson, Memoirs of the Life of Colonel Hutchinson, ed. J. Sutherland (London: Oxford University Press, 1973). Andrew Hopper, Turncoats and Renegadoes: Changing Sides During the English Civil Wars (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). David Norbrook, ‘Memoirs and oblivion: Lucy Hutchinson and the Restoration’, Huntington Library Quarterly, vol. 75, no. 2 (Summer, 2012), pp. 233-82. Peter Sherlock, Monuments and Memory in Early Modern England (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008). Alfred C. Wood, Nottinghamshire in the Civil War (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1937). Republished by Partizan Press of Nottingham, 2007.

Read More

War Widows Past and Present: The Civil War Petitions and War Widows’ Stories Projects

As we approach Remembrance Day, our blog considers the plight of all war widows, both past and present. How do the stories of our widows from the Civil Wars speak to those widowed by conflict today? Civil War Petitions was deeply honoured to join War Widows' Stories for a discussion at a public engagement event organised by Dr Nadine Muller. Click on the video below to find out more (video will open in YouTube)... These video clips are taken from an event held at ‘The Firing Line Museum’ of the Welsh Soldier at Cardiff Castle on 8 June 2018. The discussion was organised by Dr Nadine Muller of Liverpool John Moores University as part of her ‘War Widows’ Stories’ project. The project, which is funded by the AHRC works with a number of bodies including The War Widows’ Association of Great Britain to capture the lives of ‘war’s forgotten women past and present’. This discussion brought together past and present the persons of Lloyd Bowen, who is Co-Investigator on the Civil War Petitions project, as well as two widows of servicemen, Mary Moreland and Moira Kane. The discussion considered the many aspects of widowhood and the ways in which widows’ stories are often omitted or neglected in accounts of wars past and present. Part of the originality of the Civil War Petitions project is that it seeks to recover widows and their stories from such a long time ago. Although, of course, there were marked differences in the discussion of women’s experiences separated by hundreds of years, nonetheless there were some arresting similarities. Dr Bowen talked about the experience of war widows of the Civil Wars not knowing whether their husbands had perished. One of the contributors noted that she too had experienced something of the uncertainty of the battlefield, having been informed incorrectly on two occasions that her husband had died. The discussion also found similarities across time in widows’ difficulties dealing with the state and negotiating the complex bureaucracies of pensions and entitlements.

Read More

Charity in the City: Funding the Relief of Maimed Soldiers in Post-Restoration Bristol

Bristol was one of the largest cities in seventeenth-century England and was hotly contested over during the Civil Wars. Unfortunately, there are no surviving petitions and certificates, or details of payments made to maimed soldiers and war widows, from Bristol itself. Therefore there will be no data relating to the city on Civil War Petitions. However, what does survive is a large amount of data relating to how money was collected from Restoration Bristolians to fund the pensions and gratuities of soldiers and widows. As Mark Stoyle explains, this data provides an intriguing insight into how the county pension scheme operated in provincial cities... When we think of the maimed soldiers and war-widows of post-Civil War England and Wales, we tend to visualise them within a rural context: as residents of country parishes and small market towns. Yet it is important to remember, that although the great majority of the wounded and bereaved people who sought financial support from the authorities in the wake of the conflict did indeed live in the countryside - as, of course, the great majority of the general population did at this time - a small, but by no means negligible, proportion of the supplicants were city-dwellers. London - which was then, as now, by far the most populous community in the kingdom - would have accounted for the greatest number of urban maimed soldiers and war-widows, but many must also have lived in the great provincial cities of England: York, Chester, Bristol, Norwich and Exeter. Research carried out for the ‘Conflict, Welfare and Memory’ project is gradually beginning to uncover more information about the financial provision which was made in regional urban centres for individuals who had been hurt and bereaved during the civil conflict of the 1640s - and the records of the city of Bristol contain some especially illuminating information on this subject. Bristol was the second city of the kingdom in the seventeenth century, and, as one might expect, it was bitterly contested during the Civil War. Initially held for Parliament, the city was stormed and taken by Royalist forces in July 1643, with the king’s troops suffering terrible casualties during the assault. Bristol remained firmly in Charles I’s hands throughout the next two years, and served as the king’s chief military entrepot in the West, but, as the tide of war turned against the Royalists in 1645, so their grip on the countryside around the city began to weaken. In September that year, Parliament’s New Model Army first laid siege to Bristol and then, a few days later, stormed the city in their turn, slaughtering scores, perhaps hundreds, of the defenders in the process. Some Bristol men would have been killed or wounded during the two great assaults upon the city, while more would have suffered a similar fate while they were serving in the rival armies: whether because they had marched into the field of their own volition or because they had been impressed to fight against their wills. In the immediate aftermath of the war, moreover, it seems likely that appreciable numbers of wounded ex-soldiers would have gravitated to Bristol from elsewhere in the hope of finding work or charity in the city - even though such in-migration of ‘indigent persons’ was vigorously discouraged by the local governors. All in all, it is hard to doubt that men who had been hurt during the fighting of the 1640s would have been a familiar sight on the streets of post-Civil War Bristol. Because Bristol - like several of England’s other great provincial cities - was a county of itself, it possessed its own justices of the peace (or local magistrates), and its own quarter sessions court, and it is Bristol’s privileged county status which allows us to glimpse the measures which were taken to relieve wounded Royalist veterans in this particular urban community during the 1660s. In May 1661, the Parliament which had been summoned following the restoration of Charles II to the throne the year before - the so-called ‘Cavalier Parliament’ - met at Westminster and MPs subsequently passed the famous ‘Act for the relief of poor and maimed officers and soldiers who have faithfully served his Majesty and his Royal father in the late wars’. This was the act which made provision for wounded Royalist veterans - and for the wives and orphans of those who had been slain while fighting for Charles I - to receive regular financial support from their neighbours. Under the terms of the act, each parish in the kingdom was to be charged at the same weekly rate for this purpose as it had been under a previous, similar statute - passed for the relief of men who had been hurt in the wars of Elizabeth I - while the JPs of each county were to determine whether further sums of money ‘over and besides the same’ should be ‘adjudged meet to be assessed upon every parish’. The Bristol JPs soon set to work, and, at the meeting of the sessions court which took place in August 1662, new rates were laid down for each of the parishes within the county of the city of Bristol. First, the clerk of the court set out ‘the antient rate of the severall parishes within this Citty according to the Statute of 43 Elizabeth’. This rate had laid down that Bristol’s seventeen parishes would pay total sums ranging from 17s 4d per year to 8s 8d per year for the relief of local maimed soldiers. (The wealthiest parishes were those whose inhabitant had been rated at the highest sums, while the least wealthy parishes were those whose inhabitants had been rated at the lowest.) The total sums derived from this ‘ancient rate’, the clerk calculated, had been 3s 9d per week, or £9 15s per year. Now, he went on to record, ‘the new rate for the same parishes’ - this time for the relief of wounded Royalist veterans - had been assessed across the board at three times the amount of the old one, with the wealthiest parishes being rated at £2 12s per year and the least wealthy ones at £1 6s. The new assessment would bring in a total sum of 11s 3d per week, or £29 5s per year, to assist Bristolians who had either been wounded while fighting in the former king’s cause, or who had lost husbands or fathers in his service. In a subsequent entry in the quarter sessions minute book, dated 13 January 1663, the clerk provided a little more information about the way that the sums raised under the new assessment were to be raised, noting that the JPs had ordered that ‘the churchwardens and petty constables’ of each parish ‘shall truly collect ever afterwards the said taxation … and pay the same over … quarterly within ten days before every Quarter Sessions to Captain John Hix, who is appointed Treasurer [for the maimed soldiers] by this court’. There is no further information in the minute book about Hix (or Hicks), but his title suggests that he may himself have served in Charles I’s army, and that that is why he had been chosen by the JPs to oversee the collection and distribution of the monies for the relief of ‘maimed [Royalist] officers and soldiers’. The clerk concluded by noting the JPs had instructed, first, that ‘this order be delivered from time to time from one churchwarden to another for the continual collection of the said taxation as aforesaid, without any further direction of this court’, and, second, that any officers who failed to gather the rate would suffer the penalties laid down in the original Elizabethan statute. Sadly, no lists of the Bristolians who benefited from these careful arrangements appear to have survived. We may guess that wounded ex-Royalist soldiers who lived in the city and county of Bristol petitioned the justices for pensions - just as they did in other counties across the kingdom - and that those whose petitions were approved were then recommended to Hix for payment. What is clear is that Hix himself did not long remain in office, for in October 1663 the clerk recorded that ‘the court hath this day appointed Mr Thomas Prigg to be Treasurer of all such … sums of money as shall be rated … within … this city towards the relief of … maimed soldiers’. A year later, Prigg himself was replaced by another (ex?) military man, named in the minute book only as ‘Captain Smart’. On 4 October 1664, the clerk noted that ‘Captain Smart is this day chosen Treasurer of the moneys for maimed soldiers in the room of Mr Prigg and the churchwardens of the several parishes are to take notice thereof accordingly’. Smarte’s tenure was to prove lengthier than that of his predecessors. In 1668, he was asked by the justices to continue as ‘Treasurer for the maimed soldiers and indigent officers … for this year ensuing’, and he was similarly entreated two years later. Our final glimpse of Smart comes on 21 August 1671. On this day, the JPs ordered that the Chamberlain of Bristol should pay the sum of £25 5s which he had recently received from ‘George Wilkins the collector’ - was this as much as Wilkins had managed to gather from the £29 5s per year which was formally due from the city parishes? - to Smart, while Smart himself was ‘desired to issue out the same to the widows and maimed soldiers’. These last words make it clear that, as late as 1671, the widows of former Royalist soldiers, as well as wounded Royalist soldiers themselves, were continuing to be supported by their neighbours in the city. Sadly, no further references to maimed soldiers - or to the financial provision which was made for supporting them - appear in the Bristol quarter sessions minute books for 1672-1705, so we will have to turn to other sources as we seek to cast new light on the neglected subject of how those who had suffered wounding and loss during the Civil Wars subsequently made shift to get by in England’s largest urban communities.

Read More

A Female Combatant: Jane Merricke of Hereford

In the materials at the heart of the ‘War, Conflict and Memory’ project, women appear almost exclusively as widows petitioning for relief after their husbands’ death in service. They can seem passive figures, using the language of need and extremity to make a case for welfare payments. Although this impression is misleading (many female petitioners were vigorous and independent advocates for themselves and their children), it is nonetheless a product of the conventions governing the transaction of petitioning authority in the seventeenth century. It is striking, then, to encounter a female petitioner who was not requesting relief because of her husbands’ demise, but rather on account of her own war service. Lloyd Bowen introduces us to Jane Merricke of Hereford... Although women did not have a formal role in the Civil War armies, recent research, including that of project member Professor Mark Stoyle, has highlighted the role of female camp followers as well as women who dressed as men and served in royalist and parliamentarian forces. Moreover, there are several high profile cases of women participating in military encounters during the Civil Wars, perhaps the most famous being Brilliana Harley’s defence of Brampton Bryan in Herefordshire during the royalist siege. She was praised by one of her captains for her ‘masculine bravery’ in the face of the enemy. Most evidence of women in military contexts concerns high status figures like Harley who were left to defend the homestead while their husbands served elsewhere. This makes Jane Merricke’s petition all the more interesting as it shows participation in a Civil War siege by an obscure and relatively low status woman. Perhaps even more striking is the fact that Jane describes herself as the wife of Henry Merricke; there is no indication that he has died at the time the petition was composed and one would expect her to be described as ‘widow’ if this were the case. It seems that Jane was not content to be a demur wife who left engagement with the local authorities to the putative head of the household. Rather she devised her petition on her own initiative and with her own agenda. Jane Merricke’s petition was addressed to the mayor and justices of the city of Hereford. This was a wholly separate jurisdiction to the county of Herefordshire and made its own provision for poor relief. Merricke’s petition was presented to the authorities after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 and detailed her service in his father’s cause during the siege of the city which lasted from 29 July until 2 September 1645. Hereford was a key target in the west of England and had changed hands several times from the beginning of the war, although the strain of royalism was always strong there. As King Charles’s fortunes waned in mid-1645, the Scottish Covenanters under Lord Leven, who were fighting alongside the English parliamentarians, surrounded the city. The town’s royalist governor, Sir Barnabas Scudamore, later praised the city’s ‘officers, gentry, clergy, citizens and common souldiers’ who ‘behaved themselves all gallantly upon their duty, many eminently’, adding ‘to particularize each would be too great a trespasse’. But we can particularize at least one of these loyal defenders. In her petition Jane Merricke described how, ‘when the Scotts beleaguered’ the city she had been ‘sorely wounded in severall parts of her bodie & limbs’. She was injured while ‘casting up worke for the defence of the … Cittie, which is not unknown to the whole Cittie’. It was clearly all hands to the pump as the royalists of Hereford scrambled to shore up their position against an impressive Scottish army. Female military support was not that unusual in the siege of a major urban centre, however. When the nearby city of Worcester was besieged in 1643, for example, it was reported that ‘the ordinary sort of women, out of every ward of the city, joined in companies, and with spades, shovels and mattocks’ went ‘in a warlike manner like soldiers’ to destroy parliament’s offensive works. Similarly, one diarist wrote of Chester women during its siege being ‘all on fire, striving through a gallant emulation to outdo our men and will make good our yielding walls or lose their lives’. Merricke is unusual, however, in that, unlike these reports where ‘women’ are referred to generically, we can identify her and differentiate her experience. Merricke’s petition had a colourful and compelling narrative underwriting her request for money. She maintained that when Charles I came to the city after its relief in September 1645, Merricke was brought before him at the marketplace. The king, ‘comiseratinge her sad mishap ... out of his gracious favour then promised [her] … that shee should be cared for’. This paints a remarkable scene. It suggests that Merricke’s fortitude and bravery were particularly noteworthy and that she had been brought before the king as an example of Hereford’s resolute royalism. Perhaps this was why she noted that the ‘whole cittie & the inhabitants thereof’ knew of her actions. Charles’s gratefulness and generosity towards the city was particularly marked at this point as the royalists were struggling elsewhere in the country. On 4 September the king granted an augmentation to the city’s arms praising effusively the Herefordians’ ‘loyalltie, courage and undaunted resolution’ during the siege as they, ‘joineing with the garrison and doing the duty of souldiers then defended themselves and repell’d their fury and assaults’. Merricke seemed emblematic of such commitment and loyalty and, given the king’s buoyant mood, he may have promised Merricke she would be looked after. However, we must also remember that Merricke was making this claim over a decade later in an effort to buttress a request for money. Her tableau of the poor woman and the monarch rather flies in the face of what we know about Charles’s tendency to distance himself from his subjects. He was something of an aloof monarch who did not mix readily with the people. While Merricke may not have invented the episode, might she have embellished and augmented the encounter for her own ends? It is impossible to be certain, but her petition nonetheless shows how relatively lowborn subjects could be skilled at composing petitions to tell compelling stories in the hope of obtaining a favourable outcome from the authorities. Raising the siege of Hereford was one of a diminishing number of military bright spots for the royalists in 1645. The city finally fell to parliamentarian forces under Colonel John Birch on 18 December that year and the parliamentarian tide swept that over Hereford engulfed the rest of England and Wales in the following months. There was little prospect of Jane Merricke receiving any recompense until the restoration of monarchy in 1660. Even then, however, she claimed to have petitioned the authorities several times without success. Undeterred, she wrote another entreaty requesting consideration of ‘her sad condicon & her poore estate’. Merricke asked for an annual pension from the city elders to look after her and her children. An endorsement on her petition which now resides among the corporation’s papers at the Herefordshire Archives and Records Centre merely recorded that she was given twenty shillings from the moneys the city administered as a charitable bequest from one Mr Wood. It seems almost certain that this was a one-off gratuity rather than the annual pension she had requested. It is likely Merricke would have been disappointed with this meagre sum; it was hardly a generous return on a king’s promise. Jane Merricke's determined pursuit of compensation means she is one of the few non-elite women involved in military service during the Civil Wars who can be identified by name. The reason others are not found in the archive of welfare petitions seems clear. The legislation which established both the parliamentarian and royalist compensatory systems envisaged a clear distinction between male combatants and female dependants. This was a rigorously patriarchal society and the systems of military welfare, particularly that of the royalist side, reflected this. Perhaps emboldened by a royal promise, Jane Merricke broke ranks to request her due as a female military veteran. She was, however, a singular case among the thousands of petitioners in post-Civil War England and Wales.

Read More

Sir Thomas Fairfax, the Leeds widow and the soldier of Otley

The cases of claimants to pensions and military welfare were often strengthened by certificates of their service signed by their officers to authenticate their claims. In his capacity as parliamentarian commander-in-chief, Sir Thomas Fairfax was called upon to write many such certificates and letters. Some of these were for the maimed soldiers and war widows of his native West Riding of Yorkshire, who had served in Parliament’s northern army under his father, Ferdinando, Lord Fairfax, from 1642 to 1644. On 12 February 1645, just six days before his private entry into London as the commanding general of Parliament’s New Model Army, Fairfax took time to write a letter to Parliament’s Committee for Petitions in support of Ellen Askwith. Ellen was the widow of John Askwith of Leeds, one of Fairfax’s very first Yorkshire officers, who, despite not being from a gentry family was known to Fairfax personally. Fairfax remembered that at the outbreak of war, John Askwith ‘did very good service in encouraging the people to yield their obedience and best assistance to the king and parliament’. He recalled how John was made scoutmaster at Bradford in 1642, and that ‘by his diligence and vigilancy the enemy’s designs were often discovered, and many times the enemies forced upon great disadvantage’. In May 1643, John Askwith was commissioned as a captain of horse, five months before Cromwell wrote about the ‘plain, russet coated captain’. Raising a troop ‘which he completely armed at his own proper cost’, must have crippled Askwith financially, for which Parliament now owed his widow £960. At the fall of Bradford on 2 July 1643, Ellen Askwith and Lady Anne Fairfax were both captured. Historians have commented on the courtesy and kindness the royalists showed to Lady Fairfax, but not on their treatment of Ellen Askwith. Sir Thomas’s letter related how the royalists ‘in hatred’ for Askwith ‘ruined his house, plundered his goods, wounded his wife at Bradford, and brought her and six children into a poor and desolate condition’. On top of all these losses, a further £633 remained due to Ellen Askwith for John’s arrears of pay at his death, which occurred on 23 July 1644, possibly from wounds that he received at Marston Moor, where his troop suffered terrible losses. Ellen was ordered to be paid £1,000 out of the composition fine charged upon the royalist, Thomas, Viscount Savile of Howley, but it remains unclear how far these debts were ever settled. Like hundreds of other parliamentarian widows, Ellen was forced into action to recoup what was owed her husband. She discovered to Parliament’s Committee for the Advance of Money the concealed estates of a supposed local royalist, Thomas Wood of Beeston, whose rents she was assigned to receive from Wood’s tenants. In 1655, her executrix, Anne Askwith, complained to the Committee that Wood’s tenants continued to with-hold these rents. How far Anne was reimbursed for her and her family's suffering in the parliamentary cause remains unknown. Despite his absence in southern England, Fairfax was named on the commission of the peace in all three of Yorkshire’s Ridings. In April 1648, he succeeded his father Ferdinando, 2nd Baron Fairfax, as Custos Rotulorum (Keeper of the Rolls and leading Justice of the Peace) for the West Riding. In July 1649, at which time Fairfax was sitting in the Rump Parliament’s Council of State, Fairfax signed a certificate for presentation at the Leeds quarter sessions on behalf of Anthony West, who had been ‘desperately wounded at the storming of Selby’, on 11 April 1644, ‘by being shot through the body with a brace of bullets’. Still carrying these wounds five years later, it is likely West was known to Fairfax personally because he was from Fairfax’s native parish of Otley. The Justices recognised that West’s wounds made him unfit for work, paying him a gratuity of 10s and recommending that the general sessions at Pontefract award him a pension for life. The following year a generous pension of £5 per year was ordered, and West was still receiving small gratuities from the justices as late as 1658. Fairfax may have personally identified with Anthony West because both men had personal experience of the pains that gunshot wounds inflicted. Fairfax had been shot through the shoulder at Helmsley Castle in 1644, and shot through the wrist at Selby in July 1643, perhaps even close to the very spot where West had been struck down nine months later. By the time he reached his fifties, Fairfax’s wounds increasingly confined him to the wheelchair now on display at the National Civil War Centre, Newark Museum (on loan courtesy of the kindness of his modern-day relative, Tom Fairfax). You can read more about Fairfax in Andrew Hopper, ‘Black Tom’: Sir Thomas Fairfax and the English Revolution (Manchester University Press, 2007), and in Andrew Hopper and Philip Major, eds, Englands Fortress: New Perspectives on Thomas, 3rd Lord Fairfax (Routledge, 2014).

Read More

Meet a Magistrate: Richard Hutton of Goldsborough Hall in context

In our first ever blog, we were introduced to a petitioner, one of the more colourful characters amongst our Civil War claimants. But what of the Justices of the Peace who were the primary targets of the majority of our petitions? Many of these too had led interesting lives, and their complex back-stories must have had a profound effect on the way in which they negotiated their way through their magisterial duties during the Civil War years - including administering the county pension scheme. To mark the release of the petitions from the West Riding of Yorkshire on to Civil War Petitions next week, we welcome Ronald Hutton to introduce us to the family of one Restoration JP who heard and endorsed petitions from maimed soldiers and war widows in that county... Richard Hutton’s endorsement of a petition from maimed old royalist soldiers, thirty years after the Civil War, brings home vividly to me how much the vicissitudes of political fortune could affect one gentry family, from the West Riding of Yorkshire, during the mid-seventeenth century. Richard was the third generation of eldest sons of that family to hold that name, and destiny had treated each in utterly different ways, even though they had all held to the same, moderate and constitutionally monarchist politics, throughout. The story is given a special poignancy by the fact that the family concerned happens to be my own. The first Richard was from a Cumberland family and made a great success as a lawyer in London, rising by the 1630s to be Chief Justice of the Common Pleas and a knight, and buying an estate in the West Riding on which he built the mansion of Goldsborough Hall. Unhappily for him, he happened to be in office when Charles 1 imposed Ship Money on the English and John Hampden challenged his right to do so. The king asked the twelve judges to pronounce on the case, and though five eventually found against the Crown, Sir Richard was the only one to say explicitly that the monarch had no right to tax his people in any way without parliamentary consent. He fell into royal disfavour as a result, and he died soon after. His son duly became the second Sir Richard, of Goldsborough, and saw his father vindicated when the Long Parliament abolished Ship Money as illegal. This Hutton, however, turned against the reformist party in the Parliament when he decided that it was going too far, and threatening the traditional order in Church and State which his father had defended against the Crown. As a result, when Civil War broke out in 1642 he joined the royalists, garrisoning Knaresborough Castle for the King, raising an infantry regiment for his northern army, and helping to defend Pontefract Castle when most of the North was lost. The castle was relieved in early 1645, and Sir Richard came out of it to join the King’s Northern Horse, fighting with it at Naseby and dying with it when most of it was destroyed at Sherburn near the end of the war. Our third Richard was therefore left the son of a royalist martyr and with an inheritance diminished by fines and plunder. Notwithstanding, he engaged in conspiracy against the republican regimes and was imprisoned as a result. He must have been overjoyed in 1660 when the monarchy for which his father had died was restored, within the limits which his grandfather had sacrificed his career to impose. He resumed his place as one of the leading gentlemen and magistrates of his Riding, and he lived out the remainder of his days in peace. It was probably an especial pleasure for him to be able to do something for some of his father’s old comrades. So, in a way, our story has a perfectly happy ending.

Read More

How to Win Friends and Influence People: Negotiating Tactics of Civil War Petitioners

In a previous blog, David Appleby demonstrated the determination that was required by some petitioners to successfully secure a pension. But what other negotiating strategies were open to those ordinary people who were forced to petition their social superiors to secure financial relief in order to survive? Here, Ismini Pells reveals some of the ingenious methods adopted by maimed soldiers and war widows in search of a pension… Securing a pension or gratuity was no easy matter for maimed soldiers and war widows from the English Civil Wars. Money was in short supply. The pensions and gratuities distributed at the Quarter Sessions were dependent on a system of county-wide taxation, but years of sustained warfare had taken its toll on local economies. Many localities petitioned the Quarter Sessions to be alleviated from the burden of paying the tax for the maimed soldiers’ money. For example, in Haslingden, Lancashire, in 1661 the overseer of the poor John Ogle petitioned the sessions at Preston to be excused from caring for one maimed soldier, Raph Rishton, claiming ‘ye Town being verie Little & ye Charge soe great’ (Lancashire Archives, QSP/210/7). Taxation is seldom popular but those who lived through the Civil Wars saw taxation more than double from pre-war levels and the war-weary often simply refused to pay up. At the West Riding of Yorkshire Quarter Sessions held at Barnsley in 1649, the JPs empowered churchwardens and constables collecting money for lame soldiers to levy a 20s fine on anyone who refused to pay their contribution (WYAS, QS10/2, fol. 213). Often, one suspects, refusal was politically motivated. The former royalist stronghold of Newark, for example, was not keen to pay the taxes that funded pensions for wounded parliamentarians during the 1650s. In addition to all of this, those who sought financial relief had to compete both with other petitioners and the large volumes of routine administrative business that took place at the sessions. Yet petitioners were far from powerless. Those who sought pensions knew exactly how to manipulate the system in their favour. Petitioners’ cultural and political awareness influenced their decisions on which aspects of their stories to emphasise and (equally importantly) which to leave out. Most commonly, maimed soldiers and war widows attempted to represent themselves as the ‘deserving’ poor. Maimed soldiers often stressed how they had hitherto earned an honest living and explained how their wounds now prevented them from following their trade. For example, in his petition to the Worcestershire Quarter Sessions, Arthur Bagshaw explained how a shot to his hand had put an end to his career as a tailor. Widows usually emphasised their role as mothers and almost always mentioned their now fatherless children. Sarah Bott told the Essex magistrates that her husband’s death on campaign in Scotland had left her with ‘with five small children in a very sad and deplorable condition, destitute of necessary maintenance’. Some petitioners demonstrated an awareness of being a burden on their community and went into great detail of the lengths they had gone to maintain themselves by other ways. Johan Illery informed the Devon JPs how she had turned to ‘spynning & carding’ in an attempt to eke out a living after her husband had been hanged for his allegiance to parliament by Lord Paulet, the royalist victor at the siege of Hemiocke Castle (Devon Heritage Centre, QS/Bundles/Box 51). In Denbighshire, Mary Buckley pawned or sold all her worldly goods (NLW, Chirk Castle MS B11/6), whilst Michael Powell claimed that ‘his wyfe was constrained to wander about the towne to collect the charytie of all well disposed people’ to pay his surgeon’s fees (NLW, Chirk Castle MS B16c/44). Many were quick to draw the JPs attention to vacancies that had arisen through the death of existing pensioners but others tried more underhand tactics. Claimants who uncovered instances of previous disloyalty to the present regime amongst current pensioners’ were rewarded for their efforts. In 1648, Matthew Thackwray was awarded a pension of £2 by the Pontefract Quarter Sessions for snitching on George Thackwary and Henry Lee (WYAS, QS10/2 fols 142-3). Other pensioners attempted to cover up their dark past. John Allen and Nathaniel Lingard, both of Lincolnshire, chose to highlight how they were ‘instrumental to the happy restoration of his Majesty’ by marching south with General Monck in 1660, rather than the years of service into the Cromwellian Protectorate that had preceded their departure from Scotland (Lincolnshire Archives, LQS/A/2/1, fols 301 and 313). Above all, it was imperative for petitioners to know their target audience. Toadying up to the JPs rarely harmed. Martha Emming told the Essex bench that she did ‘humbly prostrate both herself and her cause to your grave and serious considerations, not doubting of your wonted and known clemency and justice’. Henry Norton, petitioning as late as 1710, made a cunning appeal to the Tory justices on the Northumberland bench by claiming that he had been ‘a True Member of ye high Church of England’. Obsequiousness was of the utmost importance for those claimants that aimed straight for the top and directed their petitions to figures such as Oliver Cromwell or Charles II. Often these petitions were directed back to the Quarter Sessions but those like Jeremiah Maye who were lucky enough to secure an endorsement now had added weight to their cause. After the Restoration, however, some petitioners aimed directly at finances in the king's gift. Charles II was famous for his love of dogs and there was no better way to gain the king’s attention than by mentioning his canine companions. Elizabeth Cary, whose husband had been killed in royalist service, was in receipt of a pension directly paid from the Exchequer but she petitioned Charles to transfer this to her son after her death. She was sure that the king would remember her son, as he had ‘followed your Majestie to Oxford (& was there bitten by your Majesties Dogg Cupid (as your Majestie may happily call to minde)’ (TNA, SP 29/66/153). What better way to attempt to secure the royal benevolence than a comedy moment, a mother’s love and a bit with a dog?