Sir Thomas Fairfax, the Leeds widow and the soldier of Otley

The cases of claimants to pensions and military welfare were often strengthened by certificates of their service signed by their officers to authenticate their claims. In his capacity as parliamentarian commander-in-chief, Sir Thomas Fairfax was called upon to write many such certificates and letters. Some of these were for the maimed soldiers and war widows of his native West Riding of Yorkshire, who had served in Parliament’s northern army under his father, Ferdinando, Lord Fairfax, from 1642 to 1644.

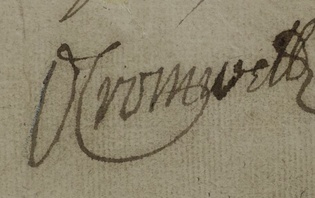

On 12 February 1645, just six days before his private entry into London as the commanding general of Parliament’s New Model Army, Fairfax took time to write a letter to Parliament’s Committee for Petitions in support of Ellen Askwith. Ellen was the widow of John Askwith of Leeds, one of Fairfax’s very first Yorkshire officers, who, despite not being from a gentry family was known to Fairfax personally. Fairfax remembered that at the outbreak of war, John Askwith ‘did very good service in encouraging the people to yield their obedience and best assistance to the king and parliament’. He recalled how John was made scoutmaster at Bradford in 1642, and that ‘by his diligence and vigilancy the enemy’s designs were often discovered, and many times the enemies forced upon great disadvantage’. In May 1643, John Askwith was commissioned as a captain of horse, five months before Cromwell wrote about the ‘plain, russet coated captain’. Raising a troop ‘which he completely armed at his own proper cost’, must have crippled Askwith financially, for which Parliament now owed his widow £960. At the fall of Bradford on 2 July 1643, Ellen Askwith and Lady Anne Fairfax were both captured. Historians have commented on the courtesy and kindness the royalists showed to Lady Fairfax, but not on their treatment of Ellen Askwith. Sir Thomas’s letter related how the royalists ‘in hatred’ for Askwith ‘ruined his house, plundered his goods, wounded his wife at Bradford, and brought her and six children into a poor and desolate condition’.

On top of all these losses, a further £633 remained due to Ellen Askwith for John’s arrears of pay at his death, which occurred on 23 July 1644, possibly from wounds that he received at Marston Moor, where his troop suffered terrible losses. Ellen was ordered to be paid £1,000 out of the composition fine charged upon the royalist, Thomas, Viscount Savile of Howley, but it remains unclear how far these debts were ever settled. Like hundreds of other parliamentarian widows, Ellen was forced into action to recoup what was owed her husband. She discovered to Parliament’s Committee for the Advance of Money the concealed estates of a supposed local royalist, Thomas Wood of Beeston, whose rents she was assigned to receive from Wood’s tenants. In 1655, her executrix, Anne Askwith, complained to the Committee that Wood’s tenants continued to with-hold these rents. How far Anne was reimbursed for her and her family’s suffering in the parliamentary cause remains unknown.

Despite his absence in southern England, Fairfax was named on the commission of the peace in all three of Yorkshire’s Ridings. In April 1648, he succeeded his father Ferdinando, 2nd Baron Fairfax, as Custos Rotulorum (Keeper of the Rolls and leading Justice of the Peace) for the West Riding. In July 1649, at which time Fairfax was sitting in the Rump Parliament’s Council of State, Fairfax signed a certificate for presentation at the Leeds quarter sessions on behalf of Anthony West, who had been ‘desperately wounded at the storming of Selby’, on 11 April 1644, ‘by being shot through the body with a brace of bullets’. Still carrying these wounds five years later, it is likely West was known to Fairfax personally because he was from Fairfax’s native parish of Otley. The Justices recognised that West’s wounds made him unfit for work, paying him a gratuity of 10s and recommending that the general sessions at Pontefract award him a pension for life. The following year a generous pension of £5 per year was ordered, and West was still receiving small gratuities from the justices as late as 1658. Fairfax may have personally identified with Anthony West because both men had personal experience of the pains that gunshot wounds inflicted. Fairfax had been shot through the shoulder at Helmsley Castle in 1644, and shot through the wrist at Selby in July 1643, perhaps even close to the very spot where West had been struck down nine months later. By the time he reached his fifties, Fairfax’s wounds increasingly confined him to the wheelchair now on display at the National Civil War Centre, Newark Museum (on loan courtesy of the kindness of his modern-day relative, Tom Fairfax).

father Ferdinando, 2nd Baron Fairfax, as Custos Rotulorum (Keeper of the Rolls and leading Justice of the Peace) for the West Riding. In July 1649, at which time Fairfax was sitting in the Rump Parliament’s Council of State, Fairfax signed a certificate for presentation at the Leeds quarter sessions on behalf of Anthony West, who had been ‘desperately wounded at the storming of Selby’, on 11 April 1644, ‘by being shot through the body with a brace of bullets’. Still carrying these wounds five years later, it is likely West was known to Fairfax personally because he was from Fairfax’s native parish of Otley. The Justices recognised that West’s wounds made him unfit for work, paying him a gratuity of 10s and recommending that the general sessions at Pontefract award him a pension for life. The following year a generous pension of £5 per year was ordered, and West was still receiving small gratuities from the justices as late as 1658. Fairfax may have personally identified with Anthony West because both men had personal experience of the pains that gunshot wounds inflicted. Fairfax had been shot through the shoulder at Helmsley Castle in 1644, and shot through the wrist at Selby in July 1643, perhaps even close to the very spot where West had been struck down nine months later. By the time he reached his fifties, Fairfax’s wounds increasingly confined him to the wheelchair now on display at the National Civil War Centre, Newark Museum (on loan courtesy of the kindness of his modern-day relative, Tom Fairfax).

You can read more about Fairfax in Andrew Hopper, ‘Black Tom’: Sir Thomas Fairfax and the English Revolution (Manchester University Press, 2007), and in Andrew Hopper and Philip Major, eds, Englands Fortress: New Perspectives on Thomas, 3rd Lord Fairfax (Routledge, 2014).