‘For the dead fathers sake’: Orphans, Petitions, and the English Civil Wars

Orphanhood – the loss of one’s parents or parent, generally a father – was commonplace in early modern England. According to estimates by Ralph Houlbrooke, around half of the population could expect at least one of their parents to die before they reached the age of 25. The outbreak of Civil War in 1642 undoubtedly led to a marked increase in the number of children who were deprived of a parent, often at a relatively young age. The pitiful cries of fatherless children were a mainstay in the print produced by both sides, featuring alongside desolated towns and weeping widows as evidence of the cruelty of the enemy and the hardships wrought by war.

In a previous blog post, Diane Strange has analysed the battles that occurred in the Court of Wards over the custody of war orphans who inherited land as tenants-in-chief of the king. But not all fatherless children were fortunate enough to be bequeathed an estate, however contested, and many found themselves facing significant poverty and hardship. The Parliament recognised that it had a duty to provide for the wives and children of its deceased servicemen – so-called ‘sword widows and sword orphans’ – and, under the terms of a 1647 ordinance, the wives and children of men killed in the Parliament’s service could apply to the justices of the peace at their local quarter sessions for financial relief. This post explores some of the petitions that were presented to county quarter sessions by, on the behalf of, or which featured Civil War orphans during the late 1640s and 1650s. These requests can be divided into broadly three categories – war widows’ petitions, those tendered by other adults (often relatives), and petitions that purported to be presented by the children themselves. By looking at examples of each type, this post illuminates some of the petitioning strategies that were deployed by different categories of claimant, as well as the treatment and care that was provided to children whose lives were disrupted by war.

By far the most prevalent form of petitions featuring war orphans were those presented by soldiers’ widows. These women regularly referred, not just to the number and age of the children that they needed to support, but to their status as ‘orphans’. Mary Birch explicitly appealed to the Parliament’s commitment to provide for ‘poore widowes and Orphans whose fathers and husbands have lost theire lives in the states service’ [Wilts and Swindon History Centre A1/110/Michaelmas 1651, f. 187]. In a similar vein, Margaret Nicholls asked the Staffordshire justices to provide such relief ‘as the lawe alloweth for such widows and Orphans’. For these women, appeals to their poor, fatherless children were deployed in an attempt to establish their eligibility for relief under the terms of the 1647 ordinance, as well as to elicit sympathy and, ultimately, sufficient money for their plight.

Indeed, in some areas, there is evidence to suggest that the payment of pensions to war widows was directly based on the needs of their children. In West Yorkshire, for example, some women were granted pensions to be paid until their youngest child was seven years old – seven being the age that children could usually expect to be apprenticed, and therefore removed from their mother’s care [West Yorks Record Office QS/10/12, f. 146, 262]. In his influential study of early modern poor relief, Steve Hindle has noted that orphans were generally regarded as ‘legitimate objects of pity’. By emphasising the condition of their children, widows attempted to combine this deep-rooted notion of desert with appeals to what they were owed as the families of men who had died for the Parliamentarian cause.

Not all children who had lost their father in military service were left with a surviving parent, however badly off. In these cases, their plight might be brought to the attention of the quarter sessions either by more distant relatives or other members of the local community. Under the terms of the Elizabethan Poor Laws, care of orphaned children was the responsibility of lineal kin, and, as a result, many petitions featuring war orphans were presented by grandparents who found themselves struggling to meet this additional burden. Poised between the longstanding conditions of the Poor Laws and the new ordinances and acts of the 1640s, these documents often exhibit a curious intersection of established familial duties and petitioning conventions coupled with the emerging expectation that service for the state had engendered new entitlements.

The elderly widow Joane Burt, for example, petitioned the Somerset quarter sessions for a ‘Pension or allowance’ on account of her extreme financial distress, caused, at least in part, by the death of her son, her daughter, her son-in-law, and the subsequent need to provide for her two orphan grandchildren. In many ways, her request was typical of petitions for poor relief throughout the seventeenth century: she emphasised her age, her inability to work, and her extreme hardship. But she also gave considerable space to an account of precisely how her sons had died. According to Burt, both had been killed fighting for the Parliament, one at the second siege of Taunton and the other ‘most cruelly hanged’ by the Royalists after the capture of Bridgewater. Though Burt didn’t explicitly appeal to the Parliament’s commitment to provide for Parliamentarian war orphans, she clearly anticipated that her sons’ fidelity was an important part of her claim, a de facto condition of desert to be considered alongside the more traditional criteria of habitation, necessity, and moral scruples. The experience of Civil War infused and re-shaped what it might mean to be a deserving claimant.

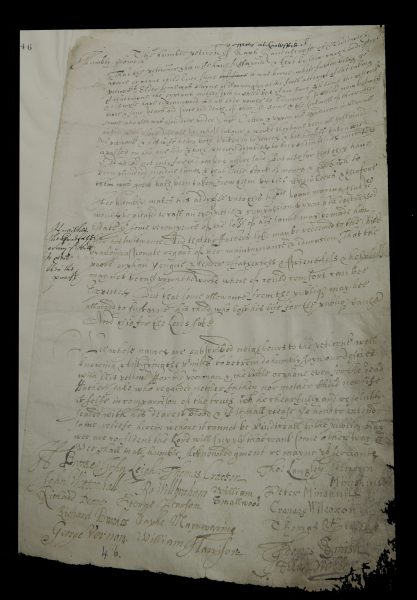

While the duty to provide for a soldier’s dependents was a latent theme of Burt’s request, other petitioners were rather more explicit. Take, for example, Raphe Ravenscroft, from Middlewhich in Cheshire, who in 1647 applied to his local quarter sessions for financial relief [Cheshire Record Office, QJF 75/1, f. 46]. Like Burt, Ravenscroft was a grandfather, who, following the loss of two sons in the Parliament’s service, had been left with a small child to maintain, a task that had been rendered even more difficult owing to his various disabilities and the loss of all his money and goods at the hands of plundering Cavaliers. Yet as well as emphasising his need, Ravenscroft’s petition made a direct connection between the loss of the child’s father in the service of the state and a corresponding duty to provide relief. He requested:

that the fathers losse may be redeemed to the child by a compassionate regard for her maintaynance and education [and that] some allowance from the publique may be allotted to sustayne his child who lost his life for the publique cause and this for the Lords sake.

The statement at the end of the petition supported by nineteen of Ravenscroft’s neighbours expressed a similar sentiment, calling on the court to provide for ‘the poorman and little orphan even for the dead fathers sake who regarded nether father nor mother nor child nor life itself in comparison of the truth w[hi]ch he cheerfully and resolutly sealed with his dearest blood’. Ravenscroft’s son had died for the ‘public cause’, for ‘truth’, and for God, a sacrifice that placed an onus on the state’s local officials to provide for his dependents. Support was something that was owed, not just to the living child, but to her deceased father – it should be provided ‘for the dead fathers sake’, a duty to the living, but also to the dead.

The petition of Raphe Ravenscroft, of Middlewich, Cheshire. 1647 (reproduced by kind permission of Cheshire Archives and Local Studies).

The note penned on the side of Ravenscroft’s petition, however, suggests that this sentiment was not one that was shared by the justices: it read, ‘if neither the Grandfather or any friends provide then the parish’. For the justices the duty to provide for poor orphans rested, first and foremost, with relatives and after that with parish officers, just as it had done since the early seventeenth century. This reluctance on the part of county justices to acknowledge war orphans as a particular category of claimant is also discernible elsewhere in the quarter session records. Humphrey Mackworth, an official in Denbighshire, referred to the 1647 act as the ‘act for reliefe of souldiers widdowes’, omitting orphans. Similarly, in Warwickshire in 1656 Thomas Burne, father-in-law of a recently deceased maimed soldier, applied to have this pension transferred to the soldier’s surviving child. The court refused, ‘the money being p[ro]perly payable’, they thought ‘to souldiers and their widdowes’ – once again, orphans were written out of the provisions of the 1647 act. The rhetorical power of orphans – ‘young and tender’, ‘fatherless’, ‘friendless’, ‘helpless’ – was not always matched by a desire to pay for their upkeep from county funds. This disparity may be attributed to the prevalence of orphans in the pre-Civil War era and the enduring expectation that these children were the responsibility of their surviving relatives or the parish in which they resided. Alternatively, it may have reflected a broader ambivalence among some officials over how far the entitlements that derived from loyal service were intergenerational: to what extent should children inherit rewards for the actions of their fathers?

All the petitions discussed thus far were presented by adults who sought money either on the orphans’ behalf or for themselves to help cover the additional costs of raising these children. However, there are also a small number of petitions that were apparently presented, and narrated, by the war orphans themselves: ‘the humble petition of Henry Gravenor, a poore distressed Infant’ [Cheshire Record Office, QJF 83/3, f. 133], ‘the humble peticon of Frances Hughson daughter of Thomas Hughson late of Macclesfield affords[aid] shoemaker (deceased)’ [Cheshire Record Office 83/1, f. 148]. In part, this formulation might be regarded as a strategic choice, a way of emphasising the lack of support available from a child’s family or friends by rendering them entirely absent from the visible material of the petition – though we might also suspect that, like most petitioners, these children probably received a significant amount of help and advice from other members of the community. They certainly knew a surprising amount about the actions and military service of parents who had been killed while they were still in infancy. However, it may also be attributed to the age of these petitioners: though a subject’s age was rarely explicitly stated, careful reading suggests that these child petitioners were usually at least six or seven years old, sometimes more. Even Henry Gravenor, a self-proclaimed ‘poore distressed Infant’ was in fact probably at least ten, his father having been killed a whole decade earlier at the taking of Beeston Castle in 1645.

Given that six or seven was the age that orphan children might usually expect to be apprenticed, and thus no longer pose such a significant financial burden, it is perhaps unsurprising that many of these child claimants laid considerable emphasis on their own inability to work. Frances Hughson, whose eyes had been damaged by a childhood episode of smallpox, explained that her eyesight had become ‘so tender and dimme’ that she was ‘altogether unable to do any things towards her livelihood’ [Cheshire Record Office QJF 83/1, f. 148], Randle Kemerley that he was not ‘of strength to get his living’ [Cheshire Record Office, QJF 77/2, f. 37]. Though their inability to work was integral to their claims, both Kemerley and Hughson nevertheless opened their requests with relatively detailed accounts of their fathers’ Civil War service and eventual deaths, at York battle [i.e. Marston Moor] and Lee Bridge, respectively. In so doing, they situated their personal misfortunes in the context of a broader national narrative, emphasising their identity not just as a poor, disabled, fatherless children, but as Parliamentarian war orphans. Though none of these children appealed directly to the provisions of the 1647 ordinance, their status as war victims who had suffered for the benefit of the Parliament and Commonwealth state was a central part of their requests and suggests the extent to which the wartime activities of a child’s parents remained of ongoing importance, imparting to these children a sense of identity not just as orphans, but as war orphans and sufferers for the Parliamentarian cause.

Imogen is a researcher and Leverhulme early career fellow in the Centre for Arts, Memory, and Communities at Coventry University. She has particular research interests in memory, post-conflict societies, and the social and cultural history of early modern Britain. She has published articles in Historical Research, Northern History, and several edited collections. Her first book, Recollection in the Republics: Memories of the British Civil Wars in England, 1649-1659, will be published next year by Oxford University Press.

Further Reading

Steve Hindle, On the Parish?: Micro-Politics of Poor Relief in Rural England, c. 1550-1750 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Andrew Hopper, ‘‘To condole with me on the Commonwealth’s loss’: The Widows and Orphans of Parliament’s Military Commanders’, in David Appleby and Andrew Hopper (eds.), Battle-scarred: Mortality, Medical Care, and Military Welfare in the British Civil Wars (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018).

Ralph A. Houlbrooke, The English Family, 1450-1700 (London: Longman, 1984).

James Marten, ed., Children and War: A Historical Anthology (New York: New York University Press, 2002).

Jeremy Seabrook, Orphans: A History (London: Hurst and Company, 2018).