‘The utter ruin of this poor town’: Quartering Soldiers in Haverfordwest during the Second Civil War.

Previous blogs have looked at the types and nature of paid employment undertaken by the mothers and wives of maimed soldiers and war widows in order to compensate for the damaging consequences of disablement and death to the family income, whilst these and other blogs have emphasised the role of the family in providing long-term care for the sick and wounded. But, as Verne Walker explains in this guest blog, it was not just the women of military families who were forced to take on new jobs or caring duties in the Civil Wars. Whilst the Civil Wars in Wales and the events of the so-called ‘Second Civil War’ in particular have often been neglected in the scholarship, she uses the mayoral accounts of the Welsh town of Haverfordwest in 1648 to provide a fascinating insight into the impact of the Civil Wars on civilian women…

‘It is one of the virtues of war that it puts the light which in peacetime is hid under a bushel in such prominence that all can see it,’ wrote Jenny Randolph Churchill on women’s work in the First World War; and this may hold true for other conflicts. The role of women can also be glimpsed through the records relating to the Second Civil War in Wales from the town of Haverfordwest. The county of Pembrokeshire saw the siege of Pembroke Castle in 1648 which lasted from Oliver Cromwell’s arrival around 24 May 1648 to its surrender on the 11 July. The siege resulted in many wounded needing care and maintenance. Although the quarter session records for Pembrokeshire, and hence any local petitions are lost, the borough records for the town of Haverfordwest, eleven miles to the north of Pembroke and the principal market town of the county, record the arrangements for the quartering and care for both prisoners and the wounded from the siege. These records show the community care which soldiers received before they returned to their families and as such fill a gap in the records that the petitions do not necessarily capture. The records reveal that work for women in Haverfordwest was contingent on the demands of the war.

Pembroke Castle, besieged in 1648 by Oliver Cromwell (photo credit: JKMMX

via Wikipedia, reproduced under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence).

The mayoral accounts for Haverfordwest for 1648 list payments to local women for the care of prisoners from the siege. The town held 84 prisoners, some of whom were injured, ‘which came from Pembroke at ‘at a cost to the town of ‘2d apiece p[er] diem’. Three unnamed women of the town were paid for fetching ‘5 burdens of straw for the prison[ers] to lye upon’ in the Shire Hall where they were held. Later a woman was paid three pence for cleaning after them. It may be considered fortunate that the men had been provided with ‘great pots to make water in’. There is nothing in these accounts that would suggest that the work that these women were doing was linked to the provision of poor relief in any way. The tasks are gendered work in the very masculine space of the shire hall. The task had the twofold benefit of helping the community in its duty of holding prisoners, but it also allowed the women to earn money to supplement family income. In records that abound with names of persons to whom payments are made it is significant that for the jobs associated with the lower orders and especially women, the recipients are rarely named.

The care of soldiers was not just a job for the lower orders; the better off also took part in the necessary tasks associated with war. The quartering of dragoons after the siege of Pembroke was also a duty that fell upon the townspeople of Haverfordwest. The town’s stretched resources caused the council to write to the leading New Model Army officer in the region, Colonel Thomas Horton, in October 1648, that the town could not afford to house further troops. Despite this, accommodation was found not only for the men but for their horses also. The task of lodging these men fell to the better off householders in the town who had the capacity for liverying horses. William Davis was paid from the town accounts, fifteen shillings for housing two men and two horses for three days in October 1648, and ‘Widdow Kneethell’ five shillings for one day. These proportions suggest that a set rate was adopted for paying the townsfolk in their support of the wounded soldiers. The rates were paid by the borough and may have reflected the rank of the men being lodged, possibly officers or troopers given the status of their lodgings and presence of horses. This did not mean that the men were affable houseguests though. Colonel Horton based at Tenby who had men quartered in Haverfordwest had to threaten his troops with disciplinary action due to some of them behaving in a rowdy manner, forcing their hosts to send them to lodge in ‘inns and alehouses’ which suggests a degree of tension between the townspeople and the quartered troops. The housing of these men may not have always been straightforward, but there were other soldiers who required more intense labour from their host households.

The care of injured soldiers, sometimes over many weeks, also fell to the middling sorts. The names of the people to whom payments were made are listed in the mayoral accounts. The payments were mostly made to men, the head of household being named for payment for the care; however, it is most likely that the actual care of the injured fell to the women, nursing being seen as work for which women were more suitable. There is no record in the accounts of any other medical aid for these men by surgeons, and the quartering could last for months with some of the men dying of their wounds. Henry Lewis was paid for the care of one man for 27 weeks until he ‘went away’. Griffith Phillips was paid three shillings and sixpence per week for one man for four weeks before the man died. One widow, Margott Fowth, received four shillings for quartering a sick soldier who later died, money being provided for his shroud and burial. Balthazar Goffe quartered John Beeres for ten weeks. This care included providing clothing and travel expenses such as the hire of horses, when the men were ready to leave. The amounts and length of stay reflect the level of care the wounded needed and hence the severity of their wounds. A petition from local people to the mayor and aldermen of the town in February 1649 makes clear that the cost to the town was becoming unmanageable and though the inhabitants had ‘cheerfully’ looked after the injured men there was a feeling that they should be moved back to their headquarters, a moot point as the army was purposely quartering the troops in the county. Whilst this petition was worded carefully to avoid any sense of recrimination, there is a clear sense that the townspeople felt they had done enough. In a letter surviving from 1652, when the town was facing crippling assessments and the local economy had been impacted by an outbreak of plague, the overall cost to the town for the care of the wounded soldiers in 1648 was put at £420 for six weeks, making it hard for the town to meet the assessment payments. However, it is clear that some injured men were cared for far longer.

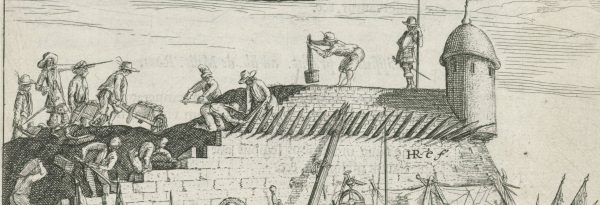

Titlepage from Henrich Ruse, ‘Versterckte Vesting’, 1654 (from the Rijksmuseum, http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.342873)

Women were previously visible in the town accounts working as low-paid, unskilled workers doing heavy tasks, such as carrying stones and water during building work, prior to and during the early years of the civil wars. This time of increased burden on the town in 1648 from quartered soldiers, both fit and wounded, also saw the order for Haverfordwest castle to be demolished to prevent it being used against the parliamentarian forces in the same way as Pembroke Castle. The cost fell on the town. An urgent rate was imposed on the surrounding hundreds and so the order to demolish the castle had a far-reaching impact in the county. There could be no doubt that the parliamentary forces were stamping their authority on the county by destroying the material culture of the local elites. The mayoral accounts show multiple payments to masons, smiths, carpenters and labourers for the demolition work on the castle in 1648. Despite the visibility of women in the early part of the war in moving stones as day-waged labourers, in this task there were no women paid for work. The task was urgent as can be seen in a draft warrant to the high constables giving instructions to collect an urgent rate for the demolition funds and extra labour was needed to help complete the task. Rather than supplementing the labour of the town with women as would be usual, the presence of colliers in the lists of payments suggest that men were brought from the nearby coal-mining areas to bolster the workforce of the town. In 1652 the cost of the demolition was put at £40. Women were paid less than men for this type of work so it should have been more cost effective for the town to use female labourers at this time, as was previously the custom. The absence of women may be due to extra domestic and nursing work needed in the town to cope with the number of wounded, sick and quartered soldiers. Their previous presence in hard labour suggests their skills were needed elsewhere. As the payments for the care of wounded men went to the head of the household it is impossible to see if payments were then made to local women for extra help. However, the absence of women in a role they would customarily take is suggestive of their engagement elsewhere.

The records from Haverfordwest show the pressure put on the town in the aftermath of the siege in Pembroke and how the community responded to the requirements placed upon them. They demonstrate how women’s work was contingent on the needs of the town during a period of crisis and how the usual work of the townswomen changed to meet the varying needs of the time.

Further Reading

Arthur Leonard Leach, The History of the Civil War (1642-9) in Pembrokeshire (London: H.F. & Witherby Ltd, 1937).

Roland Mathias, ‘The Second Civil War and Interregnum’, in Brian Howells (ed.), Pembrokeshire County History, Volume III (Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire Historical Society, 1987).

Verne Walker is studying for an MA at the University of Leicester. Her research interests include women’s work and the history of early modern Wales.