The Parents of Wounded and Fallen Soldiers: Two Case Studies from Warwickshire

Our last blog looked at the impact that a soldier’s injuries might have on his wife and their ability to provide for their children. However, when soldiers were wounded or slain, it was not just the welfare of their wives, widows, children and orphans that were placed in jeopardy. Andrew Hopper here demonstrates how sometimes the livelihoods of parents of soldiers also suffered damaging consequences. Two petitions to the parliamentarian County Committee for Warwickshire seated at Coventry reflect the impact the human costs of civil war could have on the aged parents of casualties. The second of these petitions also throws more light on a little known engagement typical of the incessant garrison warfare that played out in the west midland counties.

Our first petition came from Paul Spooner who had served as a foot soldier for three years in the garrison at Warwick Castle under Colonel Bridges. He petitioned the County Committee on 16 December 1646 that he had been ‘wounded unrecoverably’ in Parliament’s service, leaving him ‘utterly unable to stand or any way to get one penny to help himself’. He was disbanded and sent home to live with his widowed mother, in her ‘poor cottage house which standeth upon the waste’ in the hamlet of Nuthurst, 3 miles north of Henley-in-Arden. Spooner’s petition was very unusual for three reasons. Firstly, at 438 words long it was much longer than most petitions from rank and file soldiers. Secondly, it was very rare in acknowledging the income of a female relative. To show the magistrates how destitute Spooner was, the petition set out that his mother only earned 2 pence a day from spinning, a hopelessly small sum to maintain them both. Thirdly, Spooner related why his neighbours were unable to provide him poor relief; the hamlet consisted of just 2 freeholders and 4 copyholders, who were already burdened with 7 poor cottagers in receipt of alms. Spooner had petitioned the justices at the Michaelmas sessions at Warwick without success, so in order that Spooner ‘perish not for want of relief’, his neighbour Edward Wood took another petition for Spooner to the County Committee at Coventry instead. The petition reminded the Committee of their duty to relieve Spooner ‘according to ordinance and decree of parliament in that case provided’. Spooner boldly requested a monthly allowance for the rest of his life, but in mitigation dolefully added that ‘in respect of his incurable wounds and great weakness’ that was not likely to last long. The petition was successful in that the County Committee ordered their treasurer to send 30 shillings to Spooner, a sum that would have taken his widowed mother 6 months to earn from spinning.

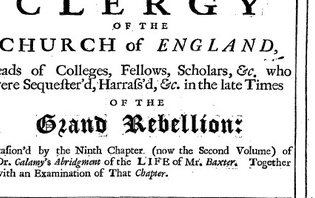

Our second petition also reminds us that parents could be dependents on their sons. It came from George Harthill, a labourer of Atherstone in north Warwickshire. His petition lamented that he had lost three sons in Parliament’s service. It requested that the County Committee settle on him the sum of £10 from the arrears of pay owed to one of them, Nicholas Harthill, a trooper under Captain Thomas Hunt. In March 1644, Hunt’s troop appears to have been sent in addition to 110 foot from Coventry to aid Colonel John Fox’s attempt to relieve the parliamentary garrison recently planted at Stourton Castle, near Stourbridge in Staffordshire. A detachment of Worcester’s royalist garrison led by Sir Gilbert Gerard met Fox’s relief force on Stourbridge Heath on 27 March. Nicknaming him ‘Tinker Fox’ in derision of his origins as a Walsall metalworker, the royalist newsbook Mercurius Aulicus gloated how Fox’s ‘unworthy trayne’ were never going to stand against a royalist force composed of ‘Voluntiers and Gentlemen of Quality’. Aulicus related that the ‘first running Rebell was the Joviall Tinker himself’, and that his men were so ‘piteously bang’d’ across the heath that 64 were killed in a pursuit that lasted 3 miles. We now know that among those who fell was Nicholas Harthill, whose father’s moving petition ended by asserting that Nicholas’s arrears would help relieve Nicholas’s aged mother and remaining siblings. The Coventry committeemen, headed by Colonel William Purefoy, who had sent Hunt’s troop into the doomed engagement at Stourton, agreed to settle on Harthill a month’s worth of his son’s pay arrears. With troopers usually paid at 2 shillings 6 pence per day, this likely amounted to around £3 and 15 shillings, some way short of half of what the bereaved father had requested.

The fate of Harthill’s wounded comrades taken prisoner at Stourbridge Heath contributed to the worsening of relations between Colonel Fox and his commander, Basil Feilding, Earl of Denbigh. Fox complained to Denbigh for preventing him from exchanging a royalist gentleman captive for those captured at Stourbridge: ‘there is great case to be made of him for the exchange of ours in prison’, who ‘would think it strange that other prisoners should be released by him and they lie for want of exchanges, which he will solve of many, especially they being wounded men and stand in need of present enlargement.’ This underlines how the urgent need to arrange exchanges for those wounded in enemy custody whose very survival was at stake became a pressing matter of conscience for commanders. This made such prisoners highly relevant to the war efforts of both sides.

Fox’s brother in law, Captain Humphrey Tudman, was among Stourton Castle’s garrison when it surrendered after Fox’s defeat on Stourbridge Heath. Aulicus scorned that ‘Colonel Tinker’s brother in law’ was ‘unworthy the charge of a guard’, and so was disarmed and released. After having commanded President Bradshaw’s guard during the trial of Charles I, John Fox was described in the Council of State’s proceedings of October 1650 as ‘ready to starve’. In great debt, he died soon after. Fox left two sons, John and Humphrey, in the care of their uncle, Captain Tudman. In 1653 Tudman warned Parliament’s Committee of Compounding that now he was left ‘without hope of his arrears’, if he was not relieved he would turn the orphans onto the streets to beg, shaming them that ‘the Commonwealths enemies’ would ‘say in reproach and especially in the county where his service was so eminent “these are the children of Colonel Fox.”’

Sources and Further Reading

The National Archives, SP28/248/II, fol. 173 (the petition of Paul Spooner, 16 December 1646).

The National Archives, SP28/248/I, fol. 38 (the petition of George Harthill, 26 October 1648).

The National Archives, State Papers 23/85, fol. 414.

British Library, Thomason Tracts E.42[26], Mercurius Aulicus, 13th week (Oxford, 1644), p. 908.

Andrew Hopper, ‘“Tinker” Fox and the politics of garrison warfare in the West Midlands, 1643–50’, Midland History, 24 (1999), p. 108.