Meet a Magistrate: Richard Hutton of Goldsborough Hall in context

In our first ever blog, we were introduced to a petitioner, one of the more colourful characters amongst our Civil War claimants. But what of the Justices of the Peace who were the primary targets of the majority of our petitions? Many of these too had led interesting lives, and their complex back-stories must have had a profound effect on the way in which they negotiated their way through their magisterial duties during the Civil War years – including administering the county pension scheme. To mark the release of the petitions from the West Riding of Yorkshire on to Civil War Petitions next week, we welcome Ronald Hutton to introduce us to the family of one Restoration JP who heard and endorsed petitions from maimed soldiers and war widows in that county…

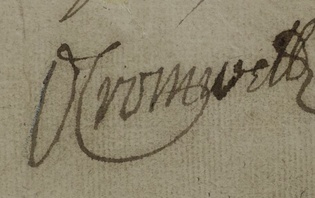

Richard Hutton’s endorsement of a petition from maimed old royalist soldiers, thirty years after the Civil War, brings home vividly to me how much the vicissitudes of political fortune could affect one gentry family, from the West Riding of Yorkshire, during the mid-seventeenth century. Richard was the third generation of eldest sons of that family to hold that name, and destiny had treated each in utterly different ways, even though they had all held to the same, moderate and constitutionally monarchist politics, throughout. The story is given a special poignancy by the fact that the family concerned happens to be my own.

The first Richard was from a Cumberland family and made a great success as a lawyer in London, rising by the 1630s to be Chief Justice of the Common Pleas and a knight, and buying an estate in the West Riding on which he built the mansion of Goldsborough Hall. Unhappily for him, he happened to be in office when Charles 1 imposed Ship Money on the English and John Hampden challenged his right to do so. The king asked the twelve judges to pronounce on the case, and though five eventually found against the Crown, Sir Richard was the only one to say explicitly that the monarch had no right to tax his people in any way without parliamentary consent. He fell into royal disfavour as a result, and he died soon after.

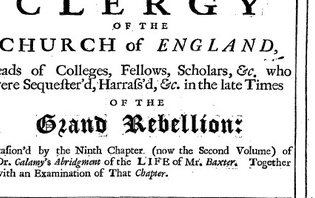

His son duly became the second Sir Richard, of Goldsborough, and saw his father vindicated when the Long Parliament abolished Ship Money as illegal. This Hutton, however, turned against the reformist party in the Parliament when he decided that it was going too far, and threatening the traditional order in Church and State which his father had defended against the Crown. As a result, when Civil War broke out in 1642 he joined the royalists, garrisoning Knaresborough Castle for the King, raising an infantry regiment for his northern army, and helping to defend Pontefract Castle when most of the North was lost. The castle was relieved in early 1645, and Sir Richard came out of it to join the King’s Northern Horse, fighting with it at Naseby and dying with it when most of it was destroyed at Sherburn near the end of the war.

Our third Richard was therefore left the son of a royalist martyr and with an inheritance diminished by fines and plunder. Notwithstanding, he engaged in conspiracy against the republican regimes and was imprisoned as a result. He must have been overjoyed in 1660 when the monarchy for which his father had died was restored, within the limits which his grandfather had sacrificed his career to impose. He resumed his place as one of the leading gentlemen and magistrates of his Riding, and he lived out the remainder of his days in peace. It was probably an especial pleasure for him to be able to do something for some of his father’s old comrades. So, in a way, our story has a perfectly happy ending.