A Female Combatant: Jane Merricke of Hereford

In the materials at the heart of the ‘War, Conflict and Memory’ project, women appear almost exclusively as widows petitioning for relief after their husbands’ death in service. They can seem passive figures, using the language of need and extremity to make a case for welfare payments. Although this impression is misleading (many female petitioners were vigorous and independent advocates for themselves and their children), it is nonetheless a product of the conventions governing the transaction of petitioning authority in the seventeenth century. It is striking, then, to encounter a female petitioner who was not requesting relief because of her husbands’ demise, but rather on account of her own war service. Lloyd Bowen introduces us to Jane Merricke of Hereford…

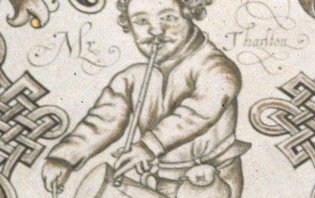

Although women did not have a formal role in the Civil War armies, recent research, including that of project member Professor Mark Stoyle, has highlighted the role of female camp followers as well as women who dressed as men and served in royalist and parliamentarian forces. Moreover, there are several high profile cases of women participating in military encounters during the Civil Wars, perhaps the most famous being Brilliana Harley’s defence of Brampton Bryan in Herefordshire during the royalist siege. She was praised by one of her captains for her ‘masculine bravery’ in the face of the enemy.

Most evidence of women in military contexts concerns high status figures like Harley who were left to defend the homestead while their husbands served elsewhere. This makes Jane Merricke’s petition all the more interesting as it shows participation in a Civil War siege by an obscure and relatively low status woman. Perhaps even more striking is the fact that Jane describes herself as the wife of Henry Merricke; there is no indication that he has died at the time the petition was composed and one would expect her to be described as ‘widow’ if this were the case. It seems that Jane was not content to be a demur wife who left engagement with the local authorities to the putative head of the household. Rather she devised her petition on her own initiative and with her own agenda.

Jane Merricke’s petition was addressed to the mayor and justices of the city of Hereford. This was a wholly separate jurisdiction to the county of Herefordshire and made its own provision for poor relief. Merricke’s petition was presented to the authorities after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 and detailed her service in his father’s cause during the siege of the city which lasted from 29 July until 2 September 1645. Hereford was a key target in the west of England and had changed hands several times from the beginning of the war, although the strain of royalism was always strong there. As King Charles’s fortunes waned in mid-1645, the Scottish Covenanters under Lord Leven, who were fighting alongside the English parliamentarians, surrounded the city. The town’s royalist governor, Sir Barnabas Scudamore, later praised the city’s ‘officers, gentry, clergy, citizens and common souldiers’ who ‘behaved themselves all gallantly upon their duty, many eminently’, adding ‘to particularize each would be too great a trespasse’. But we can particularize at least one of these loyal defenders.

In her petition Jane Merricke described how, ‘when the Scotts beleaguered’ the city she had been ‘sorely wounded in severall parts of her bodie & limbs’. She was injured while ‘casting up worke for the defence of the … Cittie, which is not unknown to the whole Cittie’. It was clearly all hands to the pump as the royalists of Hereford scrambled to shore up their position against an impressive Scottish army. Female military support was not that unusual in the siege of a major urban centre, however. When the nearby city of Worcester was besieged in 1643, for example, it was reported that ‘the ordinary sort of women, out of every ward of the city, joined in companies, and with spades, shovels and mattocks’ went ‘in a warlike manner like soldiers’ to destroy parliament’s offensive works. Similarly, one diarist wrote of Chester women during its siege being ‘all on fire, striving through a gallant emulation to outdo our men and will make good our yielding walls or lose their lives’. Merricke is unusual, however, in that, unlike these reports where ‘women’ are referred to generically, we can identify her and differentiate her experience.

Merricke’s petition had a colourful and compelling narrative underwriting her request for money. She maintained that when Charles I came to the city after its relief in September 1645, Merricke was brought before him at the marketplace. The king, ‘comiseratinge her sad mishap … out of his gracious favour then promised [her] … that shee should be cared for’. This paints a remarkable scene. It suggests that Merricke’s fortitude and bravery were particularly noteworthy and that she had been brought before the king as an example of Hereford’s resolute royalism. Perhaps this was why she noted that the ‘whole cittie & the inhabitants thereof’ knew of her actions. Charles’s gratefulness and generosity towards the city was particularly marked at this point as the royalists were struggling elsewhere in the country. On 4 September the king granted an augmentation to the city’s arms praising effusively the Herefordians’ ‘loyalltie, courage and undaunted resolution’ during the siege as they, ‘joineing with the garrison and doing the duty of souldiers then defended themselves and repell’d their fury and assaults’. Merricke seemed emblematic of such commitment and loyalty and, given the king’s buoyant mood, he may have promised Merricke she would be looked after.

However, we must also remember that Merricke was making this claim over a decade later in an effort to buttress a request for money. Her tableau of the poor woman and the monarch rather flies in the face of what we know about Charles’s tendency to distance himself from his subjects. He was something of an aloof monarch who did not mix readily with the people. While Merricke may not have invented the episode, might she have embellished and augmented the encounter for her own ends? It is impossible to be certain, but her petition nonetheless shows how relatively lowborn subjects could be skilled at composing petitions to tell compelling stories in the hope of obtaining a favourable outcome from the authorities.

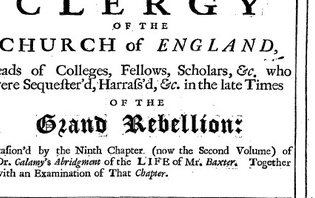

Raising the siege of Hereford was one of a diminishing number of military bright spots for the royalists in 1645. The city finally fell to parliamentarian forces under Colonel John Birch on 18 December that year and the parliamentarian tide swept that over Hereford engulfed the rest of England and Wales in the following months. There was little prospect of Jane Merricke receiving any recompense until the restoration of monarchy in 1660. Even then, however, she claimed to have petitioned the authorities several times without success. Undeterred, she wrote another entreaty requesting consideration of ‘her sad condicon & her poore estate’. Merricke asked for an annual pension from the city elders to look after her and her children.

An endorsement on her petition which now resides among the corporation’s papers at the Herefordshire Archives and Records Centre merely recorded that she was given twenty shillings from the moneys the city administered as a charitable bequest from one Mr Wood. It seems almost certain that this was a one-off gratuity rather than the annual pension she had requested. It is likely Merricke would have been disappointed with this meagre sum; it was hardly a generous return on a king’s promise.

Jane Merricke’s determined pursuit of compensation means she is one of the few non-elite women involved in military service during the Civil Wars who can be identified by name. The reason others are not found in the archive of welfare petitions seems clear. The legislation which established both the parliamentarian and royalist compensatory systems envisaged a clear distinction between male combatants and female dependants. This was a rigorously patriarchal society and the systems of military welfare, particularly that of the royalist side, reflected this. Perhaps emboldened by a royal promise, Jane Merricke broke ranks to request her due as a female military veteran. She was, however, a singular case among the thousands of petitioners in post-Civil War England and Wales.