Uncertain Authors: Who Wrote Civil War Petitions?

Among the most attractive elements of petitions from veterans and widows of the Civil Wars are their vivid personal narratives. The documents are full of drama, pathos and suffering. Terrible injuries are narrated, litanies of military service rehearsed, and vivid accounts of desperate personal circumstances given. These petitions provide a unique opportunity to learn more about the experiences of thousands of humble individuals during the tumultuous seventeenth century; individuals who have often left little or no other mark in the historical record. And yet we must be careful in thinking that these documents allow us some kind of unfettered access to the ‘real’ experiences of the personalities under whose names they were presented. In this blog, Lloyd Bowen considers the problem of authorship in Civil War Petitions.

Petitions to justices of the peace had a long pedigree by the 1640s. They thus also had an established form and a set of conventions which needed to be observed to be successful. The mode of address needed to be humble, even obsequious. Fulsome declarations of loyalty (to parliament, and, after May 1660, to the restored monarchy) needed to be made. The petitioner requested their due under the law but could be in trouble if they articulated this too forcefully and demanded money and support as their right. As a result, petitions often followed something of a script. They were accounts of individual experiences, but these experiences were moulded to meet expectations of the genre.

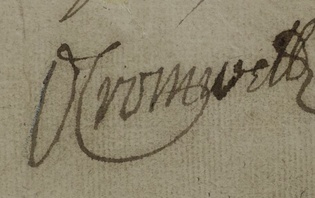

The ‘authentic voice’ of the petitioner is further called into question when we remember that many of those petitioning for relief from magistrates, monarch, parliament or military commanders were illiterate and incapable of producing the documents themselves. Many petitions were drawn up (perhaps even composed) on the petitioner’s behalf by literate individuals. The person who put pen to paper, then, might be a scrivener or a clerk who probably charged a fee. It may equally have been a literate neighbour such as a local church minister or schoolmaster. Thus, many of these documents are well-written in a neat scribal hand and follow a distinctive visual and textual format. The vast majority do not possess the signature of the ‘petitioner’ or any other textual mark indicating his or her physical interaction with the document. When such signatures are found on petitions, they are usually from members of the officer class rather than the ordinary ranks.

The authorial distance between petitioner and petition is often underlined by the fact that they were written in the third person. Individuals are described as ‘your petitioner’, and the pronouns ‘he’ and ‘she’ are standard forms of self-address.

However, there are fascinating instances when such standard formats were not followed. Many individuals below the elite were able to write and some composed their own petitions. These can sometimes be distinguished by non-scribal, often messy, handwriting, and the presence of heavily phonetic spelling. The 1648 petition of John ap Rice and his brother Evan to the parliamentarian commander Sir Thomas Myddleton, for example, addresses the latter as the ‘right onorabell Sir Thomas’, and is suggestive of self-authorship by working through the plural first person: ‘wee being well affected to this sidde [side]’. Another example is the 1643/4 petition of Corporal John Barrett to Edward Massey, governor of Gloucester. Apparently written by Barrett himself, the petition deviates from the formal mode of the genre when relating the injuries he sustained in a skirmish near Painswick. Its language is familiar, almost intimate, when discussing his ‘7 wounds in the head; 5 of them therow the scull i cut in the backe (to the bons) with a pole axe; his elbow cut off bons and all: his hand slitt downe betwine the fingers as Mr Caradine the cyerrugion [surgeon] afermeth, who hath almost cured them al (and very carfuly and willingly he hath taken the pains to do it). How to satisfie him we know not; he was never the man that asked us a farthing’.

Another intriguing example is the petition of Elizabeth Newam of Nottinghamshire. She approached the local parliamentary committee for assistance in December 1645 following her husband’s death in service. Her petition was written in a legible but not professional hand, while the spelling suggests an educated, but not trained, scribe. It articulated Elizabeth’s troubles in the first person throughout, suggesting a rare example of a female-authored text: ‘I not knowing without your honours commiseration how to subsist unless I bee forct to sell up all that I have, and soe I and my poor infant shall bee forced to beg, wheirfor I humbley intreat your honours compassion’. But even here it seems we should be cautious of ascribing ‘authorship’ too readily. At the bottom of the petition is a note in an altogether more flowing and practised hand recording the receipt of five shillings as well as ‘Elizabeth Newams marke’. Newam could not sign her name. The ‘I’s of her petition were laid down by a pen other than her own.

Other instances when the veil of authorship slips and we glimpse the individuals behind petitionary narratives survive among the material from the north Wales county of Denbighshire. Thomas Lloyd of Llanrhyader, a pressed soldier who served in the king’s armies for five years before being wounded, petitioned the county sessions in October 1667 requesting payment of a pension awarded in an earlier session but yet to be fulfilled. When discussing the commanders who had previously attested to his service, his petition reads that these men were ‘certifieinge my loyaltie’, which has been changed to the expected form of ‘his loyaltie’. Interestingly, this petition also has a rather idiosyncratic register in parts, suggesting that Lloyd’s authorship of this document was more fully present than was often the case.

Similarly, the petition presented to the Denbighshire justices by Reece Ithel of Holt at the January 1668 sessions hints at the composition process behind many of these documents. Ithel’s petition informed the justices about his service as a soldier ‘dureing all the time for most of the late unhappy warrs’, in which he had been wounded, thrice imprisoned, had his house burned, and his good stolen. The petition’s public face then slips. It lapses into the first person: ‘I was very poore & hath soe continued ever since and still am’. The text has been amended before presentation to the magistrates, however, to read ‘hee was very poore … & still is’. Similar transformations are found elsewhere; in one instance the word ‘myselfe’ as been transformed into ‘himselfe’, with the tell-tale descender of the ‘y’ pendulous and incongruous under the revised word.

These shifts in the authorial voice can be found in other parts of the country too. In Essex, for example, the 1653 petition of Martha Emming, a widow of Coggeshall, begins by relating to the justices how ‘yor peticoners husband and two of her sons’ enlisted for the parliamentary army. However, when discussing her husband’s death at York in 1644, the document moves into a mixture of the first and third person. Emming recalled how ‘at the seedg [siege] … it pleaseth god to take away the life of my said husband and soone after him one of my sonnes in Ireland to the great greeife and also to the hinderance of your poore peticioner’. The terrible trauma she had suffered bleeds through the text, providing a more immediate authorial presence than the usual remove of petitionary propriety. The interpolation of the present tense into this traumatic memory adds to the awkward mixture of raw emotion and generic distance.

It is not clear that Lloyd, Ithel or Emming personally wrote their petitions. The confused pronouns may well have been the work of scribes who were themselves inexpert in the business of formulating a petition for the bench. Equally, it may just have been a scrivener whose mind wandered during the process of transcribing after a jug or two of ale. These slips and shifts, however, are testimony to the constructed nature of these petitions and the several hands involved in their making. They remind us that while these documents bring us as close as any to the individual experience of Civil War at the level of the ordinary solider or widow, they remain far from the unmediated testimony of individual experience.