Petitions and Reparations: Elizabeth Poyer and Charles II

When King Charles II returned, somewhat unexpectedly, to the throne in 1660, he faced a deluge of petitions and entreaties from men and women who had been loyal to him and his father during the dark days of the civil wars. These petitioners hoped that the change in the political weather would bring them recognition and reward for their services. Many of these petitions were from ex-servicemen and widows of royalist soldiers, and a significant proportion were deposited among the government papers which now constitute the State Papers held at The National Archives in Kew. The Civil War Petitions team have been ferreting through this huge archive, and among the 250 plus petitions which have been identified as being relevant to the project, are some which form the primary focus for this blog. Here, Lloyd Bowen examines the petitions from Elizabeth Poyer, which throw some fascinating light on female agency in royal petitioning and also on the legacy of the Second Civil War of 1648…

Elizabeth Poyer was the widow of John Poyer of Pembroke in south west Wales. John Poyer is the subject of a recent publication by one of the project team, Lloyd Bowen: John Poyer, the Civil Wars in Pembrokeshire and the British Revolutions (University of Wales Press, 2020). Poyer was a low-born glover and merchant but rose to become a prominent Pembroke burgess. Elizabeth was the daughter of Sir Thomas Button of Worleton in Glamorgan, a vice-admiral and explorer who spent a perilous winter stranded in Hudson Bay in 1612-13 searching for the North West Passage. The two had married shortly before the civil wars.

Elizabeth Poyer was the widow of John Poyer of Pembroke in south west Wales. John Poyer is the subject of a recent publication by one of the project team, Lloyd Bowen: John Poyer, the Civil Wars in Pembrokeshire and the British Revolutions (University of Wales Press, 2020). Poyer was a low-born glover and merchant but rose to become a prominent Pembroke burgess. Elizabeth was the daughter of Sir Thomas Button of Worleton in Glamorgan, a vice-admiral and explorer who spent a perilous winter stranded in Hudson Bay in 1612-13 searching for the North West Passage. The two had married shortly before the civil wars.

In October 1641 Poyer was elected mayor of Pembroke. His election coincided with the outbreak of the Irish Rebellion which saw hundreds of Protestant refugees flood into Pembrokeshire. As the political crisis this rebellion helped engender descended into civil war, Poyer became a committed parliamentarian, something rather unusual in Wales during the early 1640s. He held Pembroke as a parliamentary garrison in the teeth of opposition from local gentry royalists.

Although Poyer ended up on the winning side of the First Civil War (1642-46), he did not reap the rewards he should have. A difficult and forceful personality, Poyer became the implacable opponent of a group of ex-royalists in Pembrokeshire who had switched sides and become trusted agents of the victorious parliament. Poyer was something of a political moderate and with the rise of radical Independency and the New Model Army from the mid-1640s, he found himself estranged from the cause of which he had once been the local figurehead.

By the beginning of 1648, Poyer was organising local resistance to his enemies and this tipped into outright disobedience when he refused to surrender Pembroke Castle to a New Model Army officer. Matters quickly gathered momentum, and soon Poyer was at the head of a substantial local insurrection against parliament. In May 1648 Poyer, along with another ex-parliamentarian officer from the area, Rice Powell, declared their support for King Charles I, who was then in army custody, and looked for assistance from Prince Charles, who was in exile in France. Poyer’s disobedience helped touch off the series of insurrections which has become known as the ‘Second Civil War’, and which saw risings in Essex, Kent, north Wales and the north of England, as well as an invasion by a Scottish ‘Engager’ force.

In south Wales, Poyer, Powell and Poyer’s brother-in-law, Rowland Laugharne, were in the vanguard of the insurrection, but they were no match for the New Model Army. Laugharne suffered a disastrous defeat at the Battle of St Fagans on 8 May 1648 and Poyer retreated behind the stout walls of Pembroke as New Model forces under the command of one Oliver Cromwell besieged the town. After a long and gruelling siege Poyer capitulated in July and was taken into parliament’s custody. The Second Civil War convinced parliament and its supporters of Charles I’s essential duplicity and was crucial in bringing about the king’s execution in January 1649.

Other royalist agents were also considered to have innocent blood on their hands, however, and Poyer and his associates soon fell under the crosshairs of parliamentary retributive justice. Poyer, along with Rice Powell and Rowland Laugharne, were brought before a court martial at Whitehall in April 1649. The tribunal found all three guilty and they were sentenced to death. Pleas for clemency (including from Elizabeth Poyer) saw the intervention of Lord General Thomas Fairfax who determined that only one man should die and that this should be determined by lot. The men agreed that an innocent child should have this responsibility and John Poyer was the unlucky individual who received a blank piece of paper rather than one inscribed with the word ‘Life’. He was executed by firing squad at Covent Garden on 25 April 1649.

Poyer’s life was thus one of drama and incident but it was also one he shared with his wife Elizabeth and their four young children who grew up in the shadow of war and conflict in Pembroke. Poyer’s demise was thus a domestic tragedy as well as a public fall from grace. As he languished in parliament’s custody in late 1648, Elizabeth’s wrote to her sister-in-law Anne Laugharne (wife of Poyer’s fellow rebel, Rowland), describing the privations she was suffering while waiting for his trial to begin. She was living a perilous existence in London and struggling to pay the rent. She requested a loan of five shillings, adding that without Anne’s support, ‘undoubtedlie else I had starved … my condicion is most stranglie sad’.

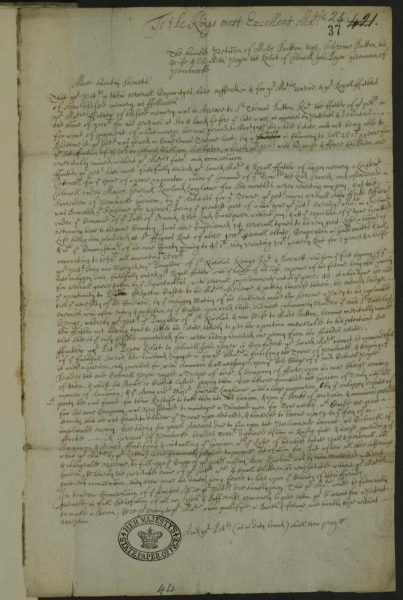

The petition of Miles and Florence Button, and Elizabeth Poyer, December 1660.

Elizabeth Poyer falls from view after her husband’s execution, doubtless keeping a low profile as the wife of a notorious rebel. With the Restoration of monarchy in 1660, however, what had once been a liability now became a public virtue, and Elizabeth was keen to obtain some recompense for her husband’s death and a decade of straitened circumstances. In December 1660, some seven months after Charles II’s return, she presented a petition to the monarch alongside her brother Miles Button, who had been taken prisoner in Pembroke, and also his wife, Florence, who was the daughter of another casualty of the 1648 rising in south Wales, Sir Nicholas Kemys. This detailed petition rehearsed how, in their ‘severall capacityes’, they had suffered in the king’s and his father’s service.

For her part, Elizabeth Poyer approached the king in a surprisingly forthright manner. She said she was ‘confident’ that Charles II ‘cannot be unmindefull of the faithfull service her husband ingaged in’ on his behalf in 1648. She then claimed that Charles, as prince, had promised John Poyer that he would satisfy him for monies Poyer disbursed in supporting the royalist cause, and Elizabeth was looking to make good on that undertaking. She produced something of a rhetorical flourish, doubtless hoping that this would add weight to her request, noting that ‘to fill upp the cupp of your petitioner’s misery, her husband was by them [i.e. parliament] murthered in Covent Garden, whereby the inevitable ruine of your petitioner with 4 small children is necessitated without your Majestys gracious comiseracion’.

This was quite a bold address which was unusual in the genre of female petitions to the king which tended instead to emphasise qualities of subjection and entreaty. It is possible that mixing her demands with that of her brother and sister-in-law blunted the message of her petition, however. It was probably also unwise for Elizabeth to mention the £8,000 arrears which she claimed her husband was owed for his action in parliament’s service! Perhaps because of these problems, it does not appear that the petition produced any tangible result.

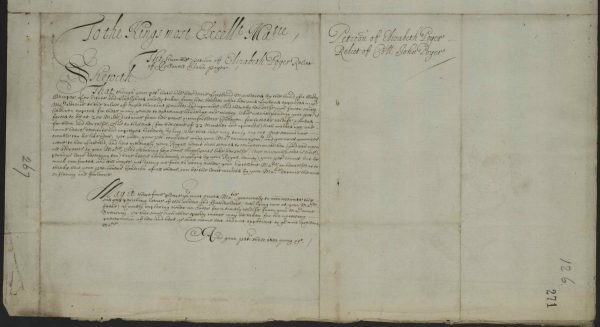

After this fruitless attempt, Elizabeth redoubled her efforts in the summer of the following year by petitioning both the king and the (royalist-dominated) Cavalier Parliament for recompense. Her July 1661 petition to Charles II was this time undertaken in her name only. Once more Elizabeth’s forthright voice can be heard even through the conventions of the royal address, beginning with the striking statement that she ‘hath had her deare husband murthered by the hand of a bloody usurper’, as well as her estate and livelihood taken away. She painted a sorry picture of her and her four children being ‘exposed for these many yeares to extreame hardshipp and misery’. While it was standard practice to emphasise, and even exaggerate, one’s suffering in a document of this kind, Elizabeth’s petition has the kinds of language and detail which suggest that she and her children had indeed suffered serious privations. Elizabeth described how she was forced to be 200 miles from her children, who were in Pembrokeshire, to seek relief, and ‘to this end (for the space of 22 monthes and upward) hath walked upp and downe heere [London] destitute and unpittyed … Soe that she may truly cry out noe sorrow nor trouble can be like hers’. This did indeed set up a pitiable image which Elizabeth then boldly juxtaposed with Charles’s, as yet, unfulfilled, promises to her husband in 1648:

yet when your petitioner considers what your majestys encouragements and gracious promises were to her husband, and how meltingly your royall heart hath seemed to compassionate her condicion upon all addresses to your majestie. And observing how some supplyants [supplicants] like her selfe (lesse miserable shee is sure, perhaps lesse deserving too) have beene aboundantly supplyed by your royall bounty) your petitioner cannot but be much comforted and still wayte, not daring soe farr to wrong either your excellent Majestie or herselfes as to thinke that your peticioners condicion of all others can be the least minded by your Majestie because the most suffering and forlorne.

This was an unusually candid and direct petition. It set up a clear quid-pro-quo which needed to be honoured in a manner that was uncommon in petitionary addresses to the monarch. There was also the clear sense here that Charles’s honour was involved in this matter, and that his not keeping the promises made to one of his most prominent supporters in 1648 was something of a stain on his regality, particularly as money, gifts and honours had flowed readily to other royal supporters following the king’s return.

The second petition from Elizabeth Poyer (July 1661)

Although such documents do not give us easy access to Elizabeth’s personality, her petition nonetheless suggests a particularly determined individual who was willing to challenge the king so that she and her family could obtain their due. As with many other petitions gathered by the ‘Civil War Petitions’ project, this document was accompanied by corroboratory material: a certificate attesting to John Poyer’s military services for the Prince in 1648, as well as independent testimony of Elizabeth’s impoverished state. It was signed by prominent participants in the south Wales revolt of 1648, including Poyer’s fellow rebel (and now Member of Parliament) Rowland Laugharne.

Despite her efforts, Elizabeth only received a grant of £100 some two years later. Although Charles II may have hoped otherwise, this did not silence the determined Widow Poyer. In 1664 she once again petitioned the king, reminding him how Poyer’s fatal actions in 1648 were ‘warranted by your owne instruction & commission’. She again raised her and her children’s sorry state, for she was now £1,500 in debt ‘in these 15 years languishment since her … husband’s death’, and maintained that ‘shee & her family [will] bee exposed to the streets’, and that she could see no way ‘to get of[f] of the plunging shee is fallen into’ without the king’s help.

Elizabeth had become aware of a grant worth £3,000 which concerned the gathering of forfeited recognisances, or promissory bonds, due to the Crown, which she wished to obtain. Effectively, Elizabeth asked to become a kind of royal debt collector. After some discussion in Council, she was indeed granted this office and finally received some reparation for her husband’s death in the royalist cause.

Elizabeth Poyer’s story is obviously unique but it demonstrates some characteristics which are common to other widows’ petitions found on the project website. It demonstrates, for example, that Elizabeth was not discouraged by the failure of her initial petition. Many widows showed considerable determination and persistence in petitioning their local quarter sessions as well as the central authorities numerous times in the hope of achieving a favourable result. Elizabeth was also emblematic of other widowed petitioners who emphasised the suffering of themselves and their children – the sorry fate of the latter being a common component of addresses designed to loosen the purse strings of a patriarchal society confronted by a household whose head (and principal breadwinner) was lost because of his loyalty.

Yet loyalty was something of an issue with Elizabeth Poyer’s representations too. Her husband had been an active arm of the parliamentary state which fought against Charles I throughout the First Civil War. Although John Poyer had died in the royalist cause, he had only declared for the king a few short months before his capture. There was an ambiguity here which may have caused King Charles II to pause before rewarding the widow of such a prominent ‘turncoat’.

It was perhaps to combat these questions of loyalty and faithfulness that Elizabeth Poyer’s petitions were so strikingly forthright in their declarations of her husband’s efforts on behalf of Prince Charles (now Charles II) and his father. John Poyer may have been late in joining the royalists but his sacrifice in the cause was the ultimate one, and the redoubtable Elizabeth was determined to see the debt paid.

Further Reading

Robert Ashton, Counter-Revolution: The Second Civil War and its Origins, 1646–8 (New Haven and London, 1992).

Lloyd Bowen, John Poyer, the Civil Wars in Pembrokeshire and the British Revolutions (Cardiff, 2020).

Andrew Hopper, Turncoats and Renegadoes: Changing Sides during the English Civil Wars (Oxford, 2012).

Brian Weiser, ‘Access and Petitioning during the Reign of Charles II’, in Eveline Cruickshanks (ed.), The Stuart Courts (Stroud, 2003), pp. 203-13.