New Wars on Old Battlefields: Disputes in Later Seventeenth-Century Brigstock, Northamptonshire

The research team behind Civil War Petitions have been very lucky with all the help and assistance that we have received from the staff of archives and record offices across England and Wales. We are indebted to their knowledge and expertise , which has helped us to identify all the relevant documents and shed new light on the local contexts in which our petitions were written. We are delighted to introduce this guest blog from Andrew North of Northamptonshire Archives and Heritage Service. As he reveals here in the fascinating case of Giles Blaston of Brigstock in Northamptonshire, there is often more to our petitions than meets the eye…

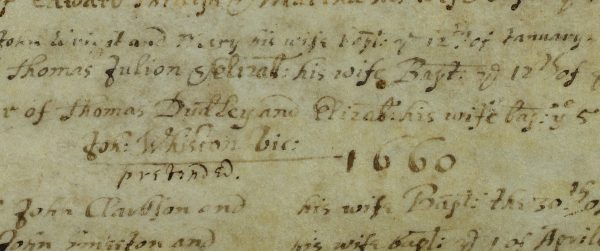

At the end of the old calendar year in March 1660, John Whiston, intruding minister in the Northamptonshire village of Brigstock, signed-off the preceding year’s sequence of baptism records in the parish register. Brigstock was a populous parish in Rockingham Forest, and Whiston was soon recording the new year’s baptisms in his small, neat handwriting. But the records in his hand break off after an entry of 16 May 1660, and the hand of Francis Lewys, who had been ejected as Brigstock’s vicar in 1655, has added the word ‘pretended’ under Whiston’s signature. Signing-off the second half of 1660’s baptisms in March 1661, Lewys made his point again, writing ‘repossessed’ beneath his own name: the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion was clearly going to take some time to make its mark in this community.

Francis Lewys’s annotations in the Brigstock parish register (photo credit: Northamptonshire Archives and Heritage Service)

Lewys’s attempt to set the record straight did not draw a line under the conflict of religious and political views in the community of Brigstock. According to the petition of Giles Blaston, a labourer there, the enmities of the 1640s were still alive and very much kicking four decades later. When Blaston petitioned the county Quarter Sessions in October 1682, the leading point of his claim for assistance was that he was still suffering ‘hardship by oppressions put upon me by divers of my neighbours in Oliver’s days well known to be of the then Godly party’. Blaston emphasised how he continued to counter the ‘persuasions and affronts of my enemies’ with his ongoing loyalty; he was ‘still [my emphasis] ready with the hazard of my life to serve the king’. Blaston also employed the more formulaic claims conventionally made by petitioners. He had suffered wounds and hardships, was elderly, poor, and had a wife to support. With a neat argumentative twist, these commonplace complaints of petitioners were cited as the reason Blaston would ‘become a scorn to my old enemies’, who, he claimed, ‘still live and flourish’.

Was this just too neat? Could the animosities of the wars have lingered so potently for so long in Brigstock, or was the petitioner overplaying his hand? Like all such petitioners, Blaston sought to maximise the grounds of his claim; but he could not risk alienating the presiding justices by making statements that could not be supported. Moreover, twenty prominent parishioners, his ‘loyal neighbours’, were ready to certify that his statements were ‘very just and true’. In part, it might have been the recent turmoil of the Exclusion Crisis that had stirred up Brigstock’s ‘Godly party’; but there is much evidence that old enmities had indeed also been kept on the boil at a local level.

In 1676, Civil War tensions in the neighbourhood had been invoked during a legal dispute over an area of ground called Weldon Plain, rights over which were also claimed by Brigstock’s adjoining parish of Weldon. Contesting the case were Thomas Barton (c.1620-1705), the head of a leading gentry family in Brigstock, and Christopher Lord Hatton (1632-1706), lord of Weldon manor. During the wars, Barton had captained a troop of horse in Sir Gervase Lucas’s ‘Belvoir Cormorants’; he subsequently seems to have acted as a royalist agent, being kept under surveillance during the Rule of the Major-Generals. Hatton’s father, also Christopher (1605-1670), spent the period ‘enforced to retire into parts beyond the seas…for the preservation of his person from the fury of the…usurpers to continue until the happy restoration of his Majesty’. He is described elsewhere in the legal case papers as ‘a person of great loyalty which through the persecutions of the times caused him to contract great debts and encumbrances upon his estate’.

Ostensibly, the land dispute then pitched a staunchly royalist member of the gentry against an equally committed royalist family from the nobility; but the Hatton side called attention to the family’s loyalty in order to build a case that accused Captain Barton’s father, also named Thomas (c.1594-1658), claiming he had ‘illegally obtained in [the] times of rebellion’ a verdict on the use of the plain in a fraudulent court action. In opposition to the royalism of both the Hattons and his own son, the elder Barton was recorded as ‘being a person of that time of great interest with the then usurpers and one who managed the affairs of the then Lord Monson, one of the regicides and murtherers of his…late Majesty’.

The language of both Giles Blaston’s petition and the legal case papers share many of the same formulaic expressions – as coercive as they are vacuous – for loyalty to the Crown. Blaston had ‘never deserted his late or now Majesty’s interest’, just as the elder Lord Hatton had displayed ‘constant adhesion to his late Majesty, King Charles the first of glorious memory’. Blaston did not write his own petition and may also have had help shaping its terms. Yet his labouring-class status had not excluded him from the approved Restoration discourse about the wars, or from the idea of artfully manipulating their memory. When he came to make his petition, he had already heard these standard forms articulated and used before justices to promote a personal claim. The 1676 court case had needed witnesses, drawing them from across the local community’s social spectrum; the Hatton side alone called over twenty deponents, one of whom was Giles Blaston.

Personal, parochial and political conflict were then deeply interwoven in post-Restoration Brigstock. Both Hatton and Blaston were opportunistically exploiting memories of the Wars in order to press their immediate personal concerns. But, in turn, the fighting of new private wars on old battlefields stoked up the wider community’s memory of past ideological division, reigniting Civil War enmities – and Brigstock’s history of volatility meant it was ready to catch fire again.

Weapons had been drawn back in 1631, when Thomas Barton senior, armed with a ‘large pikestaff and a sword’, led over forty of his fellows from Brigstock, together with some of their wives, in a riotous response to some of Lord Hatton’s men from Weldon who had attempted to cut timber on a disputed area claimed by both villages. The same Barton tried to pasture his sheep on Weldon Plain in 1634, and the dispute flared again as Hatton’s men impounded them. In 1637 Barton and his wife encouraged their neighbours not to pay Ship Money, reacting aggressively when the constable came to distrain. Having ‘great power in the late times of usurpation’, Barton senior was in the ascendancy after Naseby and working as ‘bailiff and agent’ for William, Lord Monson. In 1648 he ‘contrived’ the ‘illegal verdict’ in the fraudulent court action against the exiled Hatton to win common rights on Weldon Plain.

A defeated cavalier, Thomas Barton junior was treated as a ‘royalist suspect’ during the Interregnum. His time of ascendancy came after the Restoration, which was preceded by his father’s death in 1658, when he inherited the main family estate. The younger Thomas Barton belonged to the ranks of ‘crafty lawyers’ and used all his legal tricks to expand this estate by acquiring more land, antagonising the neighbourhood in the process. His neighbours accused him of misappropriating charitable property and of demolishing Brigstock’s school house. Legal cases with Captain Barton at their centre multiplied, the court papers characterising him as ‘so contentious…and troublesome and vexatious that he seeks the ruin and destruction of many of the poor inhabitants of Brigstock to enrich himself thereby.’

Like his father, Barton could exploit the Civil Wars for his own ends, claiming that ‘in the late times of rebellion the [school] house was in decay and some of the agents of the usurped powers sitting in [it] broke it down’. Barton’s words frame the Wars in terms of usurpation, the same characterisation of the time employed against his father. Once again, these disputes required witnesses, drawing in significant numbers of the local population and reminding them of the profound political discord they had experienced.

Captain Barton’s notoriety continued to escalate. By the early-1670s, he had been found in contempt of the county Quarter Sessions and indicted as a common barrator[1] at Northampton Assizes; but he received a warrant for a pardon ‘in consideration of his faithful services to the late and present kings’. He was even put on trial for his life, apparently facing an accusation of murder. The details of this case remain obscure, as do the reasons he managed to avoid conviction – perhaps again he was able to trade on his wartime service to the monarchy.

Not surprisingly, Barton’s disputatious activities, so many of which were rooted in, and which constantly invoked, the experience of the Civil Wars, were on everyone’s lips and provoking further controversy. On a market day in the small town of Oundle in the autumn of 1672, Edward Barton, brother of the captain, pulled off the wig of Richard Wormelayton of Brigstock, struck him and ‘knocked his head against the wall’ following ‘some discourse concerning Captain Barton’. But Edward Barton’s defence of his brother’s reputation couldn’t contain the gossip: around the same time, Lord Hatton’s steward was writing to his master at Castle Cornet, Guernsey, where he was governor, about how Barton ‘appears so odious to the country’.[2]

Captain Thomas Barton then appears to have thoroughly lived up to the reputation for predatory aggression that had earned his wartime regiment the nickname of ‘Cormorants’. His service with the regiment at Belvoir Castle is recorded in the petition he wrote in support of John Bearsley of Aldwincle, a neighbouring parish of Brigstock. Barton stated that Bearsley was a ‘faithful and valiant soldier’ and ‘truly loyal’, who had ‘never deserted his Majesty’s or his blessed father’s service’. Intriguingly, however, Barton is conspicuously absent from those who were willing to sign their name in supporting the same expressions of loyalty in Giles Blaston’s petition, despite the fact that he must have been well aware of the royalist veteran in his own village. In fact, the leading signatory on Blaston’s petition was the captain’s youngest brother, Robert, who was a prosperous farmer and a rather less confrontational member of the family. Had the captain continued to hold a grudge against Blaston for standing as a witness against him in the 1676 legal case, or was the labourer one of those ‘poor inhabitants of Brigstock’ who had been exploited by Barton? It would be no surprise if such personal grievances cut across parochial and political loyalties in this way: the mood in post-Restoration Brigstock was a febrile one, with the ruptures of war continuing to be refracted through a multifaceted prism of local tensions.

Regardless of whether he was ventriloquizing the words of his petition’s scribe, Blaston’s extraordinary conclusion catches the fractured and suspicious mood of his community perfectly: were he to be granted financial relief and a pension, he said, his ‘enemies’ would be ‘daunted’ and ‘all other good subjects be thereby encouraged to serve and honour their king and to abhor and detest treason and rebellion as the sin of witchcraft.’ On this view, the rebellion against the king had also been a rebellion against God, a deviant transgression that had brought enduring conflict to Blaston’s village. Lewys, the restored clergyman, had similarly tried to characterise the wartime experience as false and abnormal with his comment ‘pretended’. But the search for a labels that would enable the war to be personally memorialised as aberrant trickery were no more successful than the official state policy of amnesia in coming to terms with the experience. Captain Thomas Barton saw things differently. The wars had probably been the most intense and exciting time of his life; and, having survived both the siege at Belvoir Castle and state surveillance, after 1660 he was able to play out fully the role of resurgent cavalier by dominating life in Brigstock. Significantly, he retained the honorific ‘Captain’ for the rest of his days, and was still being discussed in letters a generation after his death. Perhaps, too, Brigstock lived up to the reputation of forest villages for disorder. It had been an unruly place even before the Civil Wars, which inflected existing tensions and provoked new ones – its wounds were deeper and more difficult to remedy than those of Giles Blaston, whose petition won him a pension of three pounds a year.

[1] One who stirs up vexatious legal cases and quarrels

[2] ‘Country’ here signifies a neighbourhood centred on a market town

Sources

Northamptonshire Record Office

Finch Hatton collection: FH 715; FH 1150; FH 1151; FH 3520; FH V6318/8

Quarter Sessions: QSR1/63/60; QSR1/68/63; QSR1/107; QS minute book 1668-1678

Brigstock parish collection: 48P/1; 48P/84

British Library

Additional Manuscripts: Add. MS 34014; Add. MS 19516

Parliamentary Archives

Main Papers: HL/PO/JO/10/4

Secondary Sources

Calendar of State Papers Domestic Charles II 13 Dec 1672 p. 275

Appleby, D.J., ‘”The traitor in our own hearts”: representations of loyalty and animosity in the Restoration archives’ – unpublished conference paper