Margaret Nightingale: War Widow – and Witch?

In recent years historians have become increasingly interested in the occult dimension of the English Civil War: in the attempts which were made by Parliamentarian and Royalist propagandists to capitalise on the contemporary fear of witches, and in the ways in which that fear manifested itself on the ground during the conflict – most notoriously, perhaps, during the terrible witch-hunt which broke out in Parliamentarian-controlled East Anglia in 1645, under the direction of the self-styled ‘Witchfinder General’, Matthew Hopkins. It is well known that the great majority of those who were prosecuted as witches in early modern England were women, and that, of these women, a high proportion were widows. Hopkins’s very first victim, indeed, was Elizabeth Clarke: a one-legged widow from Manningtree, in Essex, who was hanged at Chelmsford for witchcraft in July 1645. There is nothing to indicate that Clarke’s deceased husband had been a soldier – but recent research for the ‘Conflict, Welfare and Memory’ project has uncovered evidence which suggests that at least one seventeenth-century Englishwoman did suffer the devastating twin blows of first seeing her husband slain as a soldier during the Civil War and, then, many years later, undergoing prosecution as a witch. This blog-post, by Mark Stoyle, tells her story…

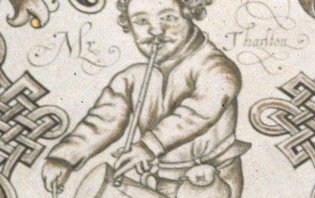

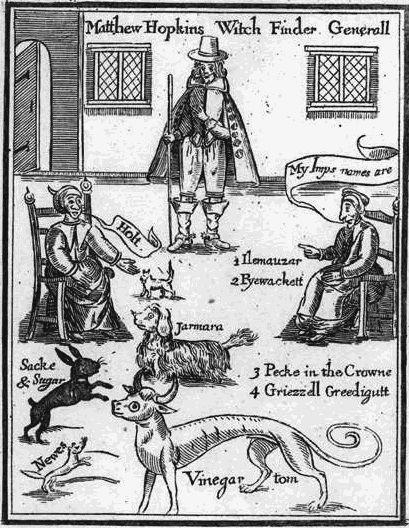

Frontispiece from Matthew Hopkins’s The Discovery of Witches, 1647 (Image from Wikipedia, reproduced under a Creative Commons licence).

In April 1661, almost a year after the Restoration of Charles II, the justices of the peace of the city and county of Exeter – the regional capital of South West England and then one of the kingdom’s largest urban communities – assembled at the Guildhall in order to sit as magistrates at the Easter meeting of the city’s quarter sessions court. With their judicial duties discharged, the JPs then turned to consider the annual rate which was levied on the nineteen city parishes for the support of the poor and, having set the amount for the following year, went on to direct that a large proportion of the monies raised should be spent, as usual, on providing relief for three specific groups of local ‘paupers’: the prisoners in the town gaol; the residents of the alms-houses at St Anne’s Chapel, in the suburban parish of St Sidwell’s, and the residents of St Katherine’s alms-houses, near the Cathedral. Yet, on this particular occasion, the JPs departed from their normal practice by identifying a fourth group of indigent persons whom they deemed to be worthy of the citizens’ collective charity and by ordering that ‘the residue’ of the monies raised from the rate should be paid ‘to the maymed souldiers [of this city] as the Justices … shall … direct’. Having recorded the JPs’ instruction in the quarter session order book, the clerk of the court then listed at the bottom of the page the names of nine men – four of them inhabitants of St Sidwell’s, and one of them a resident of St Katherine’s alms-house – all of whom, he noted, were from henceforth to be paid pensions of between £1 10 s. and £3 a year.

We know for certain that one of the maimed soldiers who was supported by the rate had been wounded while serving in the Royalist army during the Civil War, and it seems highly likely that most, if not all, of the others had been too. The JPs’ order of April 1661 thus suggests that, in Exeter – as in several other English counties – magistrates had begun to award pensions to ex-Royalist soldiers who had been injured and had consequently fallen on hard times even before they had been specifically enjoined to do so in the Act ‘for the releife of poore and maimed … souldiers who have faithfully served his majesty and his royal father in the late wars’ which was to be passed by the so-called ‘Cavalier Parliament’ during the following year. As well as instructing JPs to arrange for the provision of pensions to former soldiers who had been injured while fighting for Charles I, the Act of 1662 also instructed them to provide unspecified forms of financial relief to ‘the Widowes … of such as have died … in the said service’. The inclusion of this latter clause in the Act almost certainly explains why, when the JPs next met to review the poor rate, in April 1662, they ordered that pensions should be paid, not only to ten maimed soldiers living within the county and city of Exeter, but to two soldiers’ widows as well.

About the first of these women, a certain ‘Barbara Slooman’, little further evidence survives. The value of the pension awarded to her was left blank by the clerk of the court in 1662, but in subsequent years she enjoyed an annual stipend of £1 10 s. The second female recipient of the magistrates’ bounty was ‘Margarett Knightingall, widow’, under whose name the clerk scribbled the three additional words ‘her husband slayne’, meaning, presumably, that Nightingale’s husband had been killed while serving as a Royalist soldier during the Civil War. For reasons which remain unclear, Nightingale was awarded a slightly larger pension than Slooman: a stipend of £2 a year. This was a respectable sum – especially as post-Restoration JPs were far more likely to palm-off Royalist soldiers’ widows with a one-off gratuity of a few shillings than to award them a regular pension of the type which Slooman and Nightingale had secured.

This atypical generosity becomes all the more surprising when we consider that, less than a year before Margaret Nightingale was awarded a widow’s pension by the Exeter magistrates, she had been tried before those same magistrates as a suspected witch. Nightingale had initially been denounced to the civic authorities in June 1661, after Maria Knowsley – the infant daughter of William Knowsley, a baker of Holy Trinity parish – had been ‘violently taken in fitts’. Desperate to find out what was wrong with his child, Knowsley had sought an acquaintance’s advice, only to receive the chilling assurance ‘that the said child was bewitched by some person’. Upon hearing these words, the terrified Knowsley had at once recalled that, at the time when Marie had first gone into convulsions, ‘one Margaret Knightingall of … [Exeter], widowe, was then in his house who hath beene formerlie convicted for witchcrafts & inchantments’. Knowsley had promptly rushed to inform the mayor of Exeter – who was also one of the JPs – of his suspicions: assuring him that he ‘verilie beleiveth that the said Margarett Knightingall did practice on his childe & is [the] cause of its distemper’, and adding, as further proof of his claim, ‘that the childe hath beene taken in such fitts [several times] since att the sight of the said Margaret Knightingall’.

Knowsley’s accusation had clearly been taken extremely seriously by the mayor and by his fellow-magistrates – all the more so as the unfortunate child had died soon afterwards – and in September 1661 Margaret Nightingale had accordingly been brought before the sessions court at the Guildhall and charged with having murdered Maria Knowsley through the exercise of ‘witchcrafts, inchantments, charmes and sorceries’. Had Nightingale been found guilty on this charge, she could well have been sentenced to death by hanging, as so many other supposed ‘witches’ had been in England over the course of the preceding century. Yet, by the time of the Restoration, judicial scepticism about the possibility of proving, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that the supernatural ‘crime’ of witchcraft had really been committed was beginning to grow. It may well have been partly as a result of this shifting intellectual climate that the trial jury, or the judge – or possibly both – had eventually concluded that Nightingale was not guilty of bewitching the dead child, and the widow had been permitted to go free.

How can we explain the fact that Margaret Nightingale, a woman whom we know for certain to have been indicted for witchcraft at the Exeter sessions court in September 1661 – and whom we may strongly suspect, on the basis of William Knowsley’s testimony, to have been actually convicted of that same offence on a previous, unspecified, occasion – should have been awarded a widow’s pension by the town magistrates just seven months later: this at a time when the granting of financial relief to both maimed soldiers and their widows tended to depend not only on those individuals’ wartime conduct but also on their social reputations? The sheer size of Exeter’s population – well over 12,000 people in 1662 – makes it hard to believe that Nightingale and Slooman were the only Royalist soldiers’ widows in the city and had therefore been chosen as the lucky recipients of pensions on that basis alone. It also seems unlikely – though not, perhaps, impossible – that Nightingale had a personal connection with one of the justices.

Is it conceivable, then, that the decision to award Nightingale a pension was the result of some sort of politico-religious tussle within the city’s ruling elite? Could members of Exeter’s powerful puritan/non-conformist faction have chosen to encourage, or even to orchestrate, the prosecution of an ex-Royalist soldier’s wife as a witch? And could a majority group of Anglican/Royalist JPs on the bench have then chosen to celebrate Nightingale’s acquittal – and to thumb their noses as their discomfited rivals – by awarding her an annual stipend? Or is the most likely reason that this reputed ‘witch’ was granted a pension simply that she was even more wretchedly poor than were the other Royalist soldiers’ widows who were scratching out a living in post-Restoration Exeter? Whatever the true circumstances may have been, the story of Margaret Nightingale reminds us that, while, in many ways, the experiences of the men and women who lived through the English Civil War exhibit clear parallels with those of individuals who have lived through much more recent conflicts, in other respects, the experiences of mid-seventeenth-century combatants and their families now seem almost impossibly remote.

Further Reading

M. Gaskill, Witchfinders: A Seventeenth Century English Tragedy (London, 2005).

S. Beale, ‘Military Welfare in the Midland Counties during and after the British Civil Wars, 1642-1700’, Midland History, 45 (2020), pp. 1-18.

M. Stoyle, ‘Witchcraft in Exeter: The Cases of Bridget Wotton and Margaret Nightingale’ (forthcoming in Devon and Cornwall Notes and Queries, 2020).