‘Killing a King’: The Sack of Leicester and the Trial of Charles I

On 17 to 19 December 2019, a three-part docudrama called ‘Charles I: Killing a King’, produced by Darlow Smithson Productions, was screened on BBC4. In the first episode, presenter Lisa Hilton met up with the principal investigator of the Civil War Petitions project, Professor Andrew Hopper in the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland. Whilst much of the focus of the series was on the high politics surrounding the trial and execution of Charles I, Prof. Hopper used the project’s petitions from Leicestershire to explain how the suffering experienced by ordinary people during the Civil Wars contributed towards the movement to bring the king to justice. In this blog, Prof. Hopper examines a key feature of these petitions – the memory of the sack of Leicester by the royalists in 1645 – in more detail…

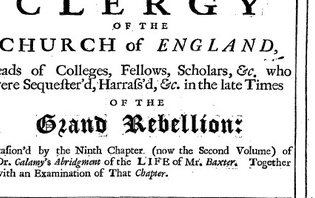

In places where surviving petitions from the county Quarter Sessions are scarce, the project has been unearthing petitions from among collections of corporation records, some previously unused by historians. Thirteen such petitions survive among the Borough Hall Papers of Leicester, many of which refer to their claimants’ losses during the sack of Leicester by Charles I’s field army on the night of 31 May 1645. In this bloody assault, the royalists lost 400 men and were no doubt in an ugly mood by the time they penetrated the earthwork defences. The garrison had been insufficient to man the perimeter so it had been supplemented by a scratch force of 900 armed civilians. This made the boundary between soldier and civilian a blurred one in the eyes of their assailants. Few escaped. London newsbooks soon reported that the royalists had killed defenders and civilians who had been trying to surrender. The parliamentarian Bulstrode Whitelocke accused the royalists of having stripped and raped the women of the town. 140 cartloads of plunder were removed from the town and sent northward to royalist-held Newark, whilst the town authorities were faced with arranging burial for 719 bodies. On 3 June 1645, the parliamentarian scoutmaster Leonard Watson reported to Sir Samuel Luke that the sack of Leicester was ‘(if one may compare a small thing with a great) not much unlike the sack at Magdeburg.’ Magdeburg had lost 20,000 inhabitants when it was sacked by the Army of the Catholic League only fourteen years earlier in May 1631, becoming the most notorious atrocity of the Thirty Years’ War. The king’s German nephew, Prince Rupert, had directed the assault on Leicester, lending credence to parliamentarian notions that foreigners were brutalising the conflict in England.

Whilst the violence at Leicester fell far short of Magdeburg proportions, many of the survivors were ruined by it. Frances Stevens and Constance Brewin petitioned at Leicester Castle that their husbands had both served in the garrison and that they had been killed alongside their captains during the assault. The two widows declared that as a result they had ‘falne into great want and povertie’. Frances had six children to support and Constance had two. They reminded the Justices of their duty to pay them a weekly allowance ‘as by Ordinance of Parliam[en]t is mentioned to be allowed’. Their neighbour, the tailor William Summer, petitioned the mayor and aldermen concerning his terrible losses. He declared that his townhouse and orchard had been demolished before the assault took place because they had compromised the defences. During the fighting his son was killed, his possessions were carried off by the royalist soldiers, whilst ‘w[i]th the fright whereof yo[u]r petition[er]s wife hath beene distracted ever synce’. Summer struggled to provide for his five remaining children and his traumatised wife, but now stood threatened for practising his trade without being a freeman of the town. He had to quit his work as a tailor, but successfully petitioned the mayor and aldermen to be permitted to work as a botcher mending old garments.

The Turret Gateway, sometimes called ‘Prince Rupert’s Gateway’, formed part of the Newarke in Leicester (photo credit: Andrew H. Jackson on British Listed Buildings https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/101074069-turret-gateway-castle-ward/photos/46384#.XfyjMlX7TIU ).

Stevens, Brewin, Summer and many others had to live with the consequences of that fateful night for decades afterwards. Stories of royalist atrocities at Leicester lingered in parliamentarian circles and no doubt grew in the telling. When 31 prosecution witnesses were assembled for the trial of Charles I on 24 January 1649, Humphrey Browne, an husbandman from Whissendine in Rutland and an eye-witness of the sack of Leicester, was required to be among them. Leicester provided an excellent opportunity for the trial commissioners to demonstrate the ‘blood guilt’ of a king waging war on his people, because Charles had personally been present. Browne was likely procured to testify by local regicides Thomas, Lord Grey of Groby, or Colonel Thomas Wayte, and declared that he had seen the king ‘then on horseback in bright Armor in the said Towne of Leicester’. Browne gave evidence that part of Leicester’s defences – the Newarke – had surrendered on good conditions rather than having been taken by storm like the rest of the town. He claimed that the royalist soldiers broke these terms of surrender by cutting and maiming the prisoners taken inside. When royalist officers rebuked them, Browne claimed that he heard the king reply: ‘I doe not Care if they Cutt them three tymes more, for they are mine Enimies’. Whether Browne’s testimony was truthful or trumped up, it had the power to persuade because the suffering endured by the soldiers and civilians in the defence of Leicester had become notorious in how parliamentarians remembered the war.

Further reading:

Glenn Foard, Naseby: The Decisive Campaign (2nd edn., Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2004); Edward Vallance, ‘Testimony, Tyranny and Treason: the Witnesses at Charles I’s Trial’, forthcoming in a major academic journal. We are most grateful to Professor Vallance for sharing with us his excellent forthcoming article on the witnesses at the king’s trial.