Francis Steiphenson: The Life and Death of a ‘Russet-Coated’ Officer

Although Major Richard Sharpe is a fictional character, there were working-class officers in the British Army. John Shipp (1784-1834) spent his infancy as an orphan in a poorhouse. At the age of nine, he escaped from a miserable apprenticeship to enlist in the army as a drummer boy. Shipp’s intelligence and courage brought regular promotions, and eventually a lieutenant’s commission. The cost of keeping up with the officer class proved prohibitive, and he was forced to sell his commission and return to the ranks. However, he eventually obtained a second commission. He published an account of his career a few years before his death. As David Appleby reveals in this blog-post, Shipp was by no means the first of the few. Documents in the Staffordshire archives show how 150 years earlier it was possible for a common soldier to become an officer. That said, the case of Francis and Cibbel Steiphenson reveals how such people were still vulnerable to the prejudices of a hierarchical world …

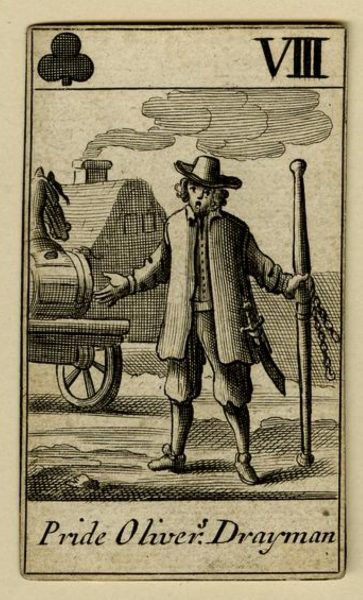

Col. Thomas Pride satirised in a pack of playing cards produced after the Restoration (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Reproduced under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence).

One of the many weapons royalists deployed against parliamentarians was snobbery. The term ‘Roundhead’ was itself calculated to invoke images of crop-haired, lice-ridden labourers and apprentices. This disdain intensified following the inception of the New Model Army, fuelled by fears that the increasing radicalisation of the parliamentarian cause would turn society upside down. The fact that many New Model officers came from obscure social backgrounds allowed royalist satirists to heap further derision on their opponents. The anonymous author of A Case for the City-Spectacles (1647), for example, described Thomas Pride as ‘a drayman boiled up to be a colonel’. Bruno Ryves argued in Micro-chronicon (1647) that there was little point in reporting the deaths of parliamentarian officers because most of them were of ‘small quality, and less fortunes’.

Royalists did not have a monopoly on snootiness. Denzil Holles, a leading opponent of Charles I, eventually became more preoccupied with opposing the rise of plebeian radicalism. A Presbyterian gentleman, he later asserted that most of the New Model’s officers were ‘mean tradesmen, brewers, tailors, goldsmiths, shoemakers and the like; a notable dunghill’. This attitude was clearly shared by the established county gentry who ran the Suffolk county committee in 1643. These well-heeled committeemen were fond of their protégé Captain Johnson, but deprecated the low-born Captain Ralph Margery. Their carping exasperated Oliver Cromwell, who gave the committee a curt assessment of Johnson’s incompetence, and praised Margery. He summed up the contrast between the two men with a sentence which would become famous: ‘I had rather have a plain, russet-coated captain, that knows what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that you call a gentleman and is nothing else.’

Although the New Model saw its share of nepotism, advancement was largely based on merit and competence. Ian Gentles has found that nearly sixteen per cent of its officers were promoted from the ranks. John Cruso had already declared in Militarie Instructions for the Cavall’rie (1632) that ‘they are not a little mistaken, which think their birth a sufficient pretence to places of honour, without any qualification or merit, there being other things more real and essential required in an officer, namely, knowledge, experience valour, dexterity etc.’ Cruso had Dutch ancestry and thousands of Englishmen had served in the Dutch army, where it was perfectly normal for a corporal to end up as a captain.

There was no compelling need for Charles I to commission plebeians, for much as he was perennially short of infantry, he was never short of officers. For parliamentarians it was the other way around: the factional infighting within Parliament’s rainbow alliance gradually reduced the number of gentlemen willing to serve as officers. This, together with the need to find replacements for those lost on campaign, compelled Parliament to cast the net more widely than their opponents. Civilians from non-gentry backgrounds such as Ralph Margery in Suffolk, Adam Eyre in Yorkshire, and Thomas Hobson, Goodhere Hunt and Colonel John Fox in Warwickshire received commissions. Lieutenant Goodhere Hunt was illiterate, as was Lieutenant William Spry of Nottinghamshire. As Andrew Hopper has observed, such men were at the margins of polite society. Nevertheless, Captain Margery was at least a minor landholder, unlike Lieutenant Francis Steiphenson of Fradswell, Staffordshire.

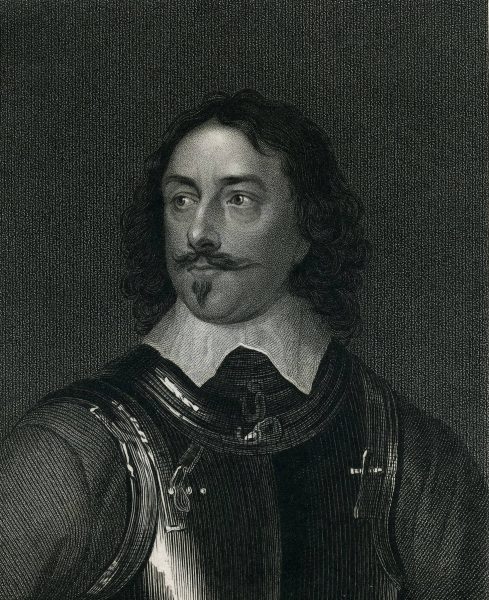

Robert Devereux, Third Earl of Essex (Fairclough Collection, reproduced by permission of the University of Leicester)

Steiphenson’s widow, Cibbel first petitioned the Staffordshire Bench in April 1651 [Staffordshire Archives and Heritage, Q/SR/272, fol. 13]. This petition and two later ones – the last submitted in October 1657 [SAH Q/SR/300, fols. 13, 14] – provide details of her husband’s life. Francis Steiphenson began his military career as a common soldier sometime around 1620, serving in Sir Horace Vere’s English brigade, in the regiment commanded by Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex. In 1620 the brigade took its place alongside other Protestant contingents in the Rhineland. Once the campaigning season had ended Lord Essex returned to England to recruit more men. He repeated the exercise every winter from 1621 to 1624. The Devereux family had property in Staffordshire, and had long enjoyed close friendships with several leading families in the region, not least that of Thomas, Lord Cromwell (a distant cousin of the then obscure Oliver Cromwell). Staffordshire was therefore an obvious place for the Earl of Essex’s recruitment drives. Cibbel Steiphenson declared in her 1651 petition that her husband had served for about thirty years, which suggests that he was one of Lord Essex’s earliest recruits.

Francis took part in several campaigns in Germany and the Low Countries. In 1657 Cibbel added to her testimony in declaring that her husband had also served in the Palatinate. This would fit with Vere’s presence there from 1621 to 1623, in support of Frederick, the Prince-Elector Palatine, James I’s son-in-law. Francis Steiphenson may therefore have served in one of Vere’s garrisons in Mannheim, Heidelberg or Frankenthal. These towns were gradually reduced by Catholic Imperial forces, with Frankenthal the last to surrender in 1623.

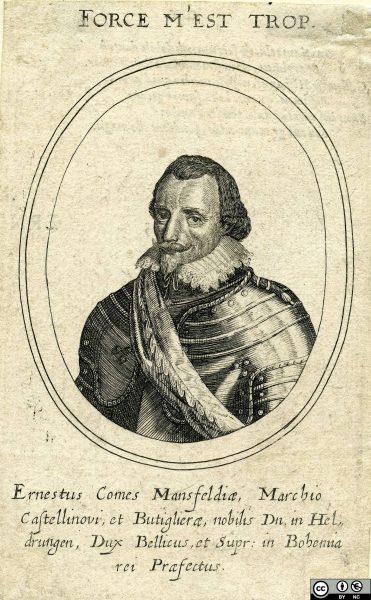

Ernst von Mansfeld, Count Mansfeld (Fairclough Collection, reproduced by permission of the University of Leicester)

Cibbel Steiphenson’s testimony indicates that Francis had returned to England by 1624. In that year King James commissioned a mercenary, Count Ernst von Mansfeld, to mount an expedition to recover the Palatinate. Thomas, Lord Cromwell was engaged to raise a regiment for Mansfeld’s expeditionary force. Cromwell, who had been created Viscount Lecale by James I, was by now experienced in warfare, having served in Ireland and at sea. The regiment had been intended for the Earl of Essex, and, like Essex before him, Lecale recruited in Staffordshire. The bulk of Mansfeld’s infantry were levies: the Privy Council had instructed provincial magistrates to disburden their counties of ‘unnecessary persons’ by conscripting unemployed males, vagrants and those living ‘lewdly and unprofitably’ [Bodleian MS Firth c. 4, fol. 107]. Turning such men into an efficient fighting force was a job for experienced officers and tough NCOs. Francis Steiphenson was a perfect choice for a sergeant: he was a seasoned soldier, and familiar with the Palatinate. Moreover, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest that recruits tended to accept discipline more readily from officers and NCOs from their own locality. Mansfeld’s expedition was a disaster. His regiments arrived on the Continent in January 1625, but most of the men died of disease, exposure and starvation without ever seeing combat.

As a veteran, Francis Steiphenson was more inured to hardship and contagion than the raw recruits. Having survived once again he found employment back in England, as a sergeant in the Staffordshire Trained Bands. His role was probably to instruct the part-time county militia in weapons drill. Cibbel Steiphenson’s declaration that he served under the Earl of Essex for a second time ‘in the north of this kingdom’ is a clear reference to the First Bishops’ War of 1639. Soon after Essex was made Lieutenant-General of Charles I’s infantry, several counties were instructed to lend him companies from their trained bands. Staffordshire sent a contingent, and it seems evident that Sergeant Steiphenson marched north with it.

The outbreak of civil war in England in 1642 saw the Earl of Essex appointed Captain-General of Parliament’s forces. Viscount Lecale’s Irish estates had been lost early in the 1641 Rising, but he returned to Ireland to command a regiment of horse for the King. His services there prompted Charles I to elevate him to the earldom of Ardglass in April 1645. Which man did Francis Steiphenson follow? The answer appears to be neither. Cibbel stated in her 1651 petition that her husband had served in Ireland ‘since the beginning of these late and still continuing distractions there’. Assuming that her reference to service ‘in the north of this kingdom’ and a later reference to service in England both refer to the Bishops’ Wars (the Second Bishops’ War being fought mainly in northern England), this would imply that Francis was shipped out in December 1641 with one of the regiments sent to the Earl of Ormond in the Pale of Dublin. He was therefore not technically a parliamentarian until June 1647, when Ormond – worried that he had insufficient forces to protect the Pale from the Catholic Confederacy – handed his troops over to Parliament. Soon after this, Steiphenson was promoted to the rank of lieutenant. The attritional nature of Irish warfare had compounded the officer shortage, and able NCOs were obvious promotion candidates.

Lieutenant Steiphenson’s luck ran out at some point around 1650. He was badly wounded, and invalided back to England, arriving in Staffordshire ‘in a languishing condition’. He was awarded an annual pension of 40 shillings per annum by the Staffordshire authorities. This was a common soldier’s pension rather than one befitting an officer, but it must be remembered that Staffordshire’s economy had been crippled by the wars. That said, a year earlier, when Lieutenant William Baggeley of Eccleshall had objected to being awarded a similar pension the county Justices had promptly raised his allowance to £10 per annum [SAH Q/SR/265, fol. 4].

Francis Steiphenson died in the winter of 1650-51. Soon afterwards, his widow heard that their son Edward had been killed in Scotland whilst serving with the New Model. Cibbel promptly petitioned the Staffordshire Bench, to request that the Justices convert her late husband’s meagre allowance into a widow’s pension. She was now old, she said, and having been ‘deprived of the comfort and help both of a husband and son’, she was ‘destitute of subsistence or livelihood’. On the face of things, Cibbel had a strong case: in addition to her husband’s long service, Edward had been steadfastly loyal to Parliament, taking part in the sieges of Chester and Lichfield, as well as other actions. The endorsements on her 1651 petition reveal that was supported by leading inhabitants in the parish of Fradswell. The fact that Wingfield Cromwell had added his signature was perhaps a mixed blessing, for the Commonwealth state considered his father, the Earl of Ardglass, a delinquent, and had fined him for his royalism. For their part, Staffordshire’s Justices had a long list of needy veterans awaiting the next pensioner’s place to fall vacant. Cibbel Steiphenson’s request was refused.

Widows often sold their clothes and household goods to survive, or relied on charity from neighbours, relations or parish officials. In extremity some were forced to beg. Cibbel had one last card to play, as she was aware that her late husband was still owed £10 by the State for arrears of pay. She pursued the matter with the Staffordshire Bench, and in October 1652 the Justices agreed to pay Francis’ arrears, in instalments of 10s a quarter. On the face of things, this should have provided Cibbel with a regular income commensurate with the discontinued pension; however, the instalments were not always paid. It was common for the Treasurers for Maimed Soldiers to prioritise the pensions of veterans, and only pay widows if any money was left. One of Cibbel’s petitions preserved in the Quarter Sessions rolls for Michaelmas 1657 [SAH Q/SR/300, fol. 13] had almost certainly been submitted to an earlier sessions. Cibbel complained in this petition that she had received no money for three quarters in a row, and now had nothing to subsist on. The Justices ordered the Treasurer to pay her 30s, and to see that future instalments were paid. However, Cibbel was forced to petition in October 1657, as the payments had lapsed once again. She reminded the Justices that they had agreed to pay her 10s a quarter until the £10 arrears had been settled in full. She had been paid for three quarters, but ‘calling for the last quarter’s payment she was (upon what pretence she knows not) denied it.’ [SAH Q/SR/300, fol. 14] Cibbel pointed out that she had not only lost her husband, but also the son who would have supported her in her old age. The Justices again admitted the default, and endorsed her petition with the order that it should be paid, and she was henceforth to receive 10 shillings every quarter until the arrears had been paid in full. One entry in the Quarter Sessions order book confirms this decision [SAH Q/SO/6, fol. 88r]. Ominously, however, another entry just two pages later states that ‘Sibill Steevenson’ should be given the disputed 30s, ‘but she is to expect no further allowance’ [SAH Q/SO/6, fol. 89v]. ‘Francis Steevenson’ was recorded merely as ‘a soldier in the Parliament’s service, deceased.’

The Justices’ repeated backsliding was in marked contrast to their sympathetic treatment of Lieutenant Baggeley. Despite having secured a pension of £10 per annum Baggeley had lived beyond his means. By January 1657, having become involved in a dubious money-making scheme, he was imprisoned for debt. He wrote from gaol to request that the Staffordshire Justices give him an advance on his usual quarterly payment [SAH Q/SR/297, fol. 12]. This initial appeal fell on deaf ears, but his wife Ann continued to collect his pension. In July 1658 the Bench relented, and authorised an advance payment [SAH Q/SO/6, fols. 67v, 81v, 103v, 104v-105r]. When Baggeley petitioned in October for a further advance, this was also granted [SAH Q/SR 304, fol. 24; Q/SO/6, fol. 109r]. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the Baggeleys received preferential treatment because Francis Steiphenson was a ‘russet-coated’ officer rather than a gentleman. Did it ever occur to Cibbel Steiphenson to petition the Lord Protector directly? Oliver Cromwell is known to have intervened personally in a number of cases, and his fondness for ‘russet-coated’ officers suggests that he would have given her a sympathetic hearing.

Further Reading

Ian Gentles, ‘The New Model officer corps in 1647: a collective portrait’, Social History, vol. 22, no. 2 (May 1997), pp. 127-144.

Andrew Hopper, ‘“Tinker” Fox and the politics of garrison warfare in the West Midlands’, Midland History, vol. 24, no. 1 (1999), pp. 98-113.

Andrew Hopper, ‘Social mobility during the English Revolution: the case of Adam Eyre’, Social History, vol. 38, no. 1 (2013), pp. 26-45.

D. W. King, ‘Ralph Margery: Cromwell’s russet-coated captain’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, vol. 58, no. 233 (Spring 1980), pp. 48-54.