Face to Face with a Maimed Soldier: Captain Richard Vaughan

As with so many historical figures who were not of the social elite, the maimed soldiers and widows whose petitions and certificates are to be found on the Civil War Petitions website are known to us only through written texts. We hear of their injuries, the wounds and scars they suffered, but we never see them. Unlike conflicts of the modern age such as the American Civil War or the First World War, there is no photographic record of the horrors of the British Civil Wars. The early modern equivalent of photography, portraiture, was confined largely to the upper gentry and town elites. There are some images of combatants injured in the Civil Wars, but these are leading generals such as John Byron, first baron Byron, a royalist colonel who received a deep wound on his cheek in a battle at Burford in 1643. This left a prominent scar which was captured in a fine oil painting produced shortly after by William Dobson. The humbler petitioners who sought relief and recompense, however, remain a faceless constituency. Except, as Lloyd Bowen reveals, not quite…

Among the collections of the British Museum there lie several pencil studies of the ceremonies for the Order of the Garter on St George’s Day, 23 April, executed in the later 1660s by the Dutch court painter Sir Peter Lely. Among their number are the great and the good such as George Morley, bishop of Winchester and Bruno Ryves, dean of Windsor and Civil War pamphleteer. However, there are also figures identified as ‘poor knights of Windsor’, members of an old order which had its origins in the fourteenth century. Retired military officers, these men received a pension of a shilling a day from the Crown and accommodation at Windsor Castle. Only one of these ‘poor knights’ is identified: Captain Richard Vaughan, a man who petitioned the Restoration authorities and received a pension as reward for his military service.[1]

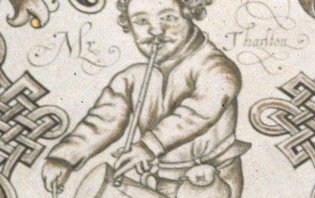

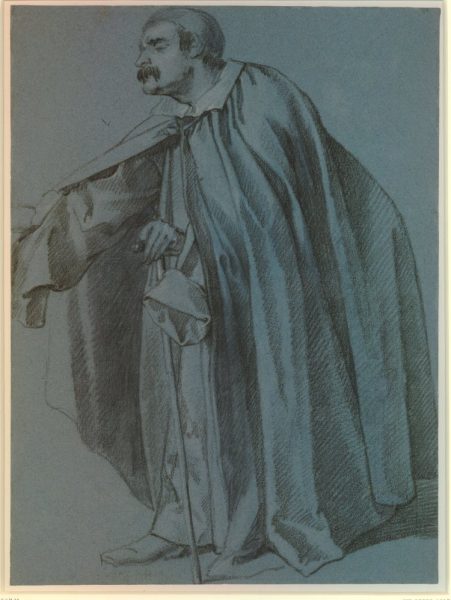

Lely’s drawing renders Vaughan as a stooped man (although he is only in his forties) using a cane to help him walk. Clothed in the Poor Knights’ red cloak and wearing a skullcap, his eyes are closed as he feels forward with his right hand. Vaughan was blind.

Captain Richard Vaughan (1847,0326.17), copyright The Trustees of the British Museum

The man who gropes towards the chapel at Windsor originally hailed from Pant Glas, Ysbyty Ifan, in Caernarvonshire. His was a minor gentry family but Richard Vaughan’s location in their pedigree is not entirely certain. This suggests that he was a younger son and certainly someone without much of a presence in local society. The family seems to have produced committed royalists, however, and another of their number, Captain Henry Vaughan, perhaps Richard’s brother, died at the siege of Hopton Castle in Shropshire in February 1644.

In his Restoration petition to the Caernarvonshire bench, Richard Vaughan described himself as having ‘for many yeares together served [the king] … very faithfully in the late unhappy wars’. Although the details of his war service are obscure, we know he served under Colonel Edward Gerard who fought at Newbury and Ludlow, as well as under his more famous brother Colonel Charles Gerard who was active in south Wales and the Marches. In one of his engagements, Vaughan ‘received a shot in the face whereby he is become blind and mayhemed’. Another record noted that he had not only lost his sight, but had also received ‘severall wounds and bruses in his late majesties service’; hence his using a walking stick despite only being in his early forties.

Vaughan must have struggled during the long years of parliamentary ascendancy. He was readily identifiable in his local community by the disability which was testament of his loyalty to the executed king. In several Restoration documents he is referred to as ‘the blind Captain’, and one imagines such a label was a liability under republican regimes. In 1660 he referred to his ‘present deplorable condicon’, which speaks of the hardships he was forced to endure.

Vaughan’s fortunes altered quickly at the Restoration, however, and as soon as was practicable, in late 1660, he petitioned the quarter sessions of Caernarvonshire and of Denbighshire for relief as a maimed soldier. In the latter county he was described as ‘of Llanrwst’ where, presumably he owned some property. In Caernarvonshire he was admitted to a pension as a lieutenant rather than a captain, which presumably was for reasons of economy rather than any reflection upon the nature of his service or the genuineness of his need. We do not know, however, what level of support he received. His petition to the Denbighshire magistrates does not appear to survive, but the bench quickly awarded him £10 per annum, making him by some distance the best remunerated pensioner in the county. This tells us that he was not a typical petitioner and not one of the lowly multitude who needed the maimed soldiers’ money simply to survive in an unforgiving world. Vaughan was a member of the lesser gentry and a royalist officer and, in a world built on rank and hierarchy, the more prominent received a larger stipend. However, the very act of petitioning for a form of poor relief suggests the degree to which Vaughan had been forced to turn away from his role as a gentleman and place himself on the mercy of the county authorities.

In 1663 Vaughan’s name was included among the list of indigent officers who received some of the £60,000 raised by Charles II as a reward for his father’s loyal commanders. In July of that year, however, Vaughan also received another piece of charitable support: admission as one of the ‘poor knights’ of Windsor. Lely thus captured ‘the Blind Captain’ at one of his first St George’s Day ceremonies. It would not be his last.

He remained at Windsor down to his death in 1700, a reminder of how young he was when serving under the Gerards, and of how Lely’s image captures Vaughan not just at the end of one life as an indigent royalist officer, but at the beginning of another as member of an exclusive circle of royal beneficiaries. However, during this time he continued to receive pension from north Wales. In January 1680 the Denbighshire bench ordered that his £10 per annum continue, despite the expiry of the 1662 act for the relief of maimed soldiers and widows the year before. This was because Vaughan’s pension had been granted in 1661 under the Elizabethan statute which provided for maimed servicemen, and was thus not subject to the ‘sunset clause’ which deprived some Restoration pensioners.

A copper plaque to Vaughan was placed in a vaulted passage at the entrance to the Great Cloisters in St George’s Chapel alongside memorials to other poor knights. It recorded his death on 5 June 1700 at the age of eighty as well as the fact that he ‘behaved himselfe with great courage … in the civill warrs and therein lost his sight by a shott’. He had drawn on the charity not only of the Crown but also of his native country for nearly forty years. He wished to give something back to the community, however, and his will provided the substantial sum of £200 ‘to maintain for ever six poor aged men’ of Ysbyty Ifan. In 1709 a complex of almshouses for this purpose was built. Although these were demolished in 1885, a new range of almshouses were erected in their place to look after the indigent poor of the parish.

A surprising amount can thus be gleaned about this obscure Civil War officer from the financial and petitionary material gathered together by the ‘Conflict, Welfare and Memory’ project, and placed online in the Civil War Petitions website. As with almost all of our subjects, this evidence is textual. Bringing this together with Lely’s image of the blind ex-serviceman moving tentatively forward on his cane, however, adds another level of pathos to the narrative of ‘the Blind Captain’, and helps put a human face to some of the sufferings endured in Britain’s Civil Wars.

[1] I am very grateful to David Evans for drawing my attention to the Vaughan drawing.