HIGHLY COMMENDED IN THE BRITISH RECORDS ASSOCIATION’S JANETTE HARLEY PRIZE 2020:

https://www.britishrecordsassociation.org.uk/press-release-winner-of-the-2020-janette-harley-prize-announced/

The Last Soldiers of the English Civil Wars

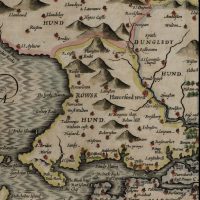

‘They say I am the last of them alive; they say I am the last roundhead’, begins the fictitious Blandford Candy in the novel The Last Roundhead by Jemahl Evans (Holland House Books, 2015). The real identity of the last surviving civil-war soldier will probably never be known for sure. The last surviving member of the Long Parliament was Sir John Holland, who sat for Castle Rising in Norfolk, and died aged 97 on 19 January 1701. We now know that quite a few of the war’s officers and soldiers outlived Sir John. Richard Cromwell, the former Lord Protector died in 1712, yet his military service is uncertain and may have been limited to a brief spell in Fairfax’s lifeguard in 1647. Mark Stoyle considers the last surviving field officer in the army of Charles I was Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Neville who also died in 1712. The last Welsh royalist officer that we know of who received a pension was Captain Richard Vaughan of Llanwrst, Denbighshire. A previous blog by Lloyd Bowen showed that Vaughan was blinded having been shot in the face, but found support among the poor knights of Windsor during the 1660s Vaughan’s portrait was drawn by Sir Peter Lely at a St George’s Day ceremony at Windsor. He did not die until 5 June 1700, aged eighty. But what of the rank and file who made up the armies on both sides? ‘Welsh Thomas’, conscripted for the royalists in Carmarthen, claimed in 1717 to have been captured at the siege of Gloucester in 1643 [Mark Stoyle, ‘Memories of the Maimed: the Testimony of Charles I’s Former Soldiers, 1660-1730’, History, 88:290 (2003), p. 207]. In counties where good records survive, our team’s research is demonstrating that significant numbers of maimed and wounded soldiers survived into the eighteenth century... Some historians have considered that the last civil-war soldier was William Walker of Ribchester, Lancashire (1613–1736). Walker fought for Charles I at the Battle of Edgehill in 1642, where he was wounded in the arm and had two horses shot under him [Charles Carlton, Going to the Wars (London, 1994), p. 349; Peter Young and Wilfrid Emberton, The Cavalier Army: Its Organisation and Everyday Life (1974), p. 144. Walker has a portrait in the University of Leicester's Fairclough Collection, but not digitised yet]. Yet no petition for a pension survives for him among the Lancashire quarter sessions. Walker attained some contemporary fame by appearing as the subject of a portrait by Gerhard Bockman and a later mezzotint by John Slack. The Ribchester parish register has a burial entry for 16 January 1736 which states ‘William Walker, a Cavalier aged 122’ [Lancashire Archives, PR2905/1/2]. The Anglican clergyman-antiquarian, Thomas Dunham Whitaker noted in 1823, that ‘At the Church of Ribchester was interred, in all probability, the last survivor of all who had borne arms in the war between Charles I and the Parliament … How long he retained his faculties I do not know; if nearly to the close of his life, he must have been a living chronicle, extremely interesting and curious’ [T.D. Whitaker, History of Richmondshire (London, 1823), vol. ii. p. 465]. The claim that Walker lived 122 years is suspicious as it far exceeds the Guinness World Record of 116 years for the world’s oldest ever man. But it remains possible that Walker had fought at Edgehill and was around 110 when he died. Another, more believable claimant is William Hiseland of Wiltshire (1620–1733). His tomb’s inscription at the burial ground of the Royal Hospital in Chelsea stated that he was born on 6 August 1620 and died aged 112 on 7 February 1733. Hiseland claimed to have fought at Edgehill in 1642 and after a long career in soldiering, with the Royal Scots at Malplaquet, despite being 89 years old in 1709. Hiseland was rewarded with a place at Chelsea Hospital until he became an out-pensioner following his marriage at the age of 100 in 1720. He sat for a portrait by George Alsop in 1730, in which a sturdy appearance is strikingly fashioned for a man of 110 years of age. Claims of advanced age were difficult to verify for certain in this period, because of the relative absence of portable, authoritative life documents. Individuals outside the parish of their birth might make exaggerated claims without the fear that sceptics would travel to their home parish to consult the baptism register. Indeed, evidence from our petitions suggests that people of advanced years did not always know their precise age. With our material for Wiltshire and Lancashire still to be uploaded, it is currently not yet known if Walker or Hiseland benefitted from county welfare payments because of their civil-war service. It is quite possible they did, because although the 1662 Act to relieve royalist maimed soldiers officially expired in England and Wales in 1679, in many counties collections for them continued. For example, the Thirsk Sessions in Yorkshire, with the advice of the Attorney General, ruled in October 1688 that although the 1662 Act had expired, the Elizabethan Act of 1601 remained in force. This enabled Yorkshiremen to petition well beyond 1700. The last surviving petition for the North Riding of Yorkshire came from Robert Wrigglesworth of Little Thirkleby in April 1701. Fittingly, he claimed to have served in Sir Robert Strickland’s regiment, the first regiment to be raised for the King, in May 1642. Our last surviving petition from the West Riding of Yorkshire came from John Genn, who claimed in January 1709 that he was 82 years old and had served under Sir Francis Fane, royalist governor of Lincoln. Genn’s petition is among eight surviving petitions from the West Riding that all date after 1700. Six of these petitioners resided in Genn’s home parish of Aston, just south of Rotherham, and two in the neighbouring parish of Treeton. The marked concentration of these last petitions in two adjacent parishes, and the supporting signatures and marks beneath them suggest the influence of a local network of parish officers and neighbours pushing these elderly men forward. Three of their petitions were signed by Samuel Trickett, rector of Aston from 1694 to 1712. Trickett used the parish register to certify that one of them, Francis Petty, was baptised in 1623, making him old enough to have served in the wars. The clustering of these last petitions may also have been due to Aston having been the seat of Sir Francis Fane (d. 1680), under whom four of the petitioners claimed to have served. There is a strong likelihood that these eight men were all known to each other, suggesting something of a network of veterans similar to the Devon tinners discussed by Mark Stoyle. These men were sharing their memories of civil war and receiving community support over 60 years later. One wonders how many similar networks elsewhere in the country persisted into the eighteenth century. The first of these eight men was Francis Jenkin of Aston, who received a pension of £2 per annum after he petitioned the Sheffield Sessions on 16 October 1700. He claimed to be ‘now Four score years ould & upwards’, and that he was a ‘souldier und[e]r King Charles ye first’ under the command of Major ‘Gore’ (possibly Major William Gower) at the siege of Hull in 1643. In 1701 two more petitioners from Aston, Anthony Davy and Richard Kelke, both secured pensions of £2 per annum having petitioned the sessions at Pontefract and Doncaster respectively. Davy claimed to be 84 years old. Both men claimed to have been among Fane’s Doncaster garrison before their capture by Lord Fairfax at the Battle of Selby on 11 April 1644, and that they both suffered imprisonment thereafter in ‘Reasor’ (likely Wressle Castle). George Inkersell of Aston secured a pension of £3 per annum when he petitioned the Barnsley Sessions on 5 October 1704 that he was aged ‘ninety years & upwards’, and that he had been no further than ¼ mile from home in two years, reassuring the justices ‘my time cannot be long in this World.’ His petition was endorsed by Trickett, along with the churchwardens and a string of neighbours. In January 1706, William Walker in neighbouring Treeton secured a pension having petitioned the Doncaster Sessions that he had been wounded serving under the command of the martyred royalists John Morris and Michael Blackburne in the Pontefract Castle garrison during 1648–9. William Hilton, also of Treeton secured a pension of £3 per annum in August 1708, having petitioned the Rotherham Sessions that he too had served under Fane as a soldier ‘to his sacred Majesty K[ing] Charles the Martyr of ever blessed Memorie.’ An even later petition survives in Northumberland: that of Henry Norton of ‘Turfe House’ in the hamlet of Steel, in Hexham parish, who, aged ‘near upon 90 years’, petitioned the midsummer sessions at Hexham in July 1710. In his petition, Henry claimed to have borne arms for King Charles I ‘of blessed memory’. Henry’s three sons had left to join ‘the Queen’s service’, and were probably fighting in Europe under the command of the Duke of Marlborough. This, he claimed, had left him in ‘miserable and deplorable circumstances’, wanting friends, and utterly dependent upon ‘the charitable help of well-disposed persons’. For good measure, he added that he had always ‘been of a good life & Conversation & a True Member of ye high Church of England’. This was a calculated appeal to the Tory JPs on the county bench and it was successful. On 12 July 1710, the JPs ordered the churchwardens and overseers of Hexham to pay Norton eight pence per week towards his maintenance. This was comparable to a pension of nearly £2 per year, and worth the effort to obtain in order to enable Norton to survive in his last years. We do not know how much longer Norton lived, or whether he witnessed the recruitment of 200 Northumbrians from his home neighbourhood for the Jacobite forces in 1715. Less than four miles northeast from Norton’s home was Dilston Hall, the seat of James Radcliffe, 3rd Earl of Derwentwater (1689-1716). A grandson of Charles II, Derwentwater was beheaded on Tower Hill on 24 February 1716 for leading the Northumbrian rebels and was buried in the family chapel at Dilston. The last civil-war pensioner for whom we currently hold firm evidence was William Leaver the elder, a pinmaker of Aylesbury. William petitioned the Buckinghamshire Sessions at Aylesbury in July 1704, that he had been in receipt of a maimed soldier’s pension of £2 per annum for several years. A separate memorandum confirmed William had served ‘his most sacred Maj[es]tie King Charles the First’. William requested successfully that his pension be augmented to £4 per annum because he was ‘fallen almost Blind whereby he is rendered very helpless poor’. He signed a receipt with his mark on 27 July 1704. His pension was increased further; by 1716 William had been receiving £6 per annum for several years. In October 1716 his pension was enlarged to £8 per annum. William petitioned again, in July 1717, for a further augmentation now that he was ‘aged 100 yeares or thereabouts’, and ‘quite blind’. The Justices raised him to £10 per annum. In January 1718 his pension was increased yet again to £12 per annum, on account that he was ‘altogether unable & uncapable to help or support himself without the assistance & helpe of some person or persons to Assist him.’ The clerk of the peace noted the special nature of this payment, at a time when ‘the number of Pentioners of this County have encreased’. William did not collect this for long because on 24 April 1718 the county treasurer was ordered to pay William’s son John Leaver 40 shillings for the costs John had incurred in his father’s burial. The last known war widow of the Civil Wars to receive money from a county treasurer was Mary, widow of William Hobbs of Chepping Wycombe. She was awarded 10 shillings as the last quarter of her late husband’s pension by the Buckingham Sessions on 11 April 1700, despite there being no legal basis by then that entitled her to relief. In 1694 William had been awarded a pension of £2 per annum for his service under Charles I, and his later service in the Anglo-Dutch Wars, with his petition supported by a certificate from the mayor of Chepping Wycombe. A comparison with the American Civil Wars reveals an even longer period over which military pensions were provided. The last widow of an American Civil War veteran was Gertrude Janeway (1909–2003). She married John Janeway, a veteran of the 14th Illinois Cavalry in 1927 and received a pension of $70 every two months until her death. Janeway was outlived by Irene Triplett of Wilkesboro, North Carolina, the last pensioner of the American Civil Wars. Irene was born in 1930, the daughter of Union veteran Moses Triplett, who died in 1938, having married a woman 50 years younger. Irene passed away on 31 May 2020, having long collected a pension of $73 per month from the Department for Veterans Affairs because of her father’s civil-war service. Individuals such as Janeway and Triplett were the inspiration behind the prize-winning novel by Allan Gurganus, Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, first published in 1989. The individuals in this blog should remind us that the human costs and living consequences of civil war do not end when treaties are signed, republics are forged or kings are restored. They remain with us generations, even centuries later.

Read More

Francis Steiphenson: The Life and Death of a ‘Russet-Coated’ Officer

Although Major Richard Sharpe is a fictional character, there were working-class officers in the British Army. John Shipp (1784-1834) spent his infancy as an orphan in a poorhouse. At the age of nine, he escaped from a miserable apprenticeship to enlist in the army as a drummer boy. Shipp’s intelligence and courage brought regular promotions, and eventually a lieutenant’s commission. The cost of keeping up with the officer class proved prohibitive, and he was forced to sell his commission and return to the ranks. However, he eventually obtained a second commission. He published an account of his career a few years before his death. As David Appleby reveals in this blog-post, Shipp was by no means the first of the few. Documents in the Staffordshire archives show how 150 years earlier it was possible for a common soldier to become an officer. That said, the case of Francis and Cibbel Steiphenson reveals how such people were still vulnerable to the prejudices of a hierarchical world … One of the many weapons royalists deployed against parliamentarians was snobbery. The term ‘Roundhead’ was itself calculated to invoke images of crop-haired, lice-ridden labourers and apprentices. This disdain intensified following the inception of the New Model Army, fuelled by fears that the increasing radicalisation of the parliamentarian cause would turn society upside down. The fact that many New Model officers came from obscure social backgrounds allowed royalist satirists to heap further derision on their opponents. The anonymous author of A Case for the City-Spectacles (1647), for example, described Thomas Pride as ‘a drayman boiled up to be a colonel’. Bruno Ryves argued in Micro-chronicon (1647) that there was little point in reporting the deaths of parliamentarian officers because most of them were of ‘small quality, and less fortunes’. Royalists did not have a monopoly on snootiness. Denzil Holles, a leading opponent of Charles I, eventually became more preoccupied with opposing the rise of plebeian radicalism. A Presbyterian gentleman, he later asserted that most of the New Model’s officers were ‘mean tradesmen, brewers, tailors, goldsmiths, shoemakers and the like; a notable dunghill’. This attitude was clearly shared by the established county gentry who ran the Suffolk county committee in 1643. These well-heeled committeemen were fond of their protégé Captain Johnson, but deprecated the low-born Captain Ralph Margery. Their carping exasperated Oliver Cromwell, who gave the committee a curt assessment of Johnson’s incompetence, and praised Margery. He summed up the contrast between the two men with a sentence which would become famous: ‘I had rather have a plain, russet-coated captain, that knows what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that you call a gentleman and is nothing else.’ Although the New Model saw its share of nepotism, advancement was largely based on merit and competence. Ian Gentles has found that nearly sixteen per cent of its officers were promoted from the ranks. John Cruso had already declared in Militarie Instructions for the Cavall’rie (1632) that ‘they are not a little mistaken, which think their birth a sufficient pretence to places of honour, without any qualification or merit, there being other things more real and essential required in an officer, namely, knowledge, experience valour, dexterity etc.’ Cruso had Dutch ancestry and thousands of Englishmen had served in the Dutch army, where it was perfectly normal for a corporal to end up as a captain. There was no compelling need for Charles I to commission plebeians, for much as he was perennially short of infantry, he was never short of officers. For parliamentarians it was the other way around: the factional infighting within Parliament’s rainbow alliance gradually reduced the number of gentlemen willing to serve as officers. This, together with the need to find replacements for those lost on campaign, compelled Parliament to cast the net more widely than their opponents. Civilians from non-gentry backgrounds such as Ralph Margery in Suffolk, Adam Eyre in Yorkshire, and Thomas Hobson, Goodhere Hunt and Colonel John Fox in Warwickshire received commissions. Lieutenant Goodhere Hunt was illiterate, as was Lieutenant William Spry of Nottinghamshire. As Andrew Hopper has observed, such men were at the margins of polite society. Nevertheless, Captain Margery was at least a minor landholder, unlike Lieutenant Francis Steiphenson of Fradswell, Staffordshire. Steiphenson’s widow, Cibbel first petitioned the Staffordshire Bench in April 1651 [Staffordshire Archives and Heritage, Q/SR/272, fol. 13]. This petition and two later ones – the last submitted in October 1657 [SAH Q/SR/300, fols. 13, 14] – provide details of her husband’s life. Francis Steiphenson began his military career as a common soldier sometime around 1620, serving in Sir Horace Vere’s English brigade, in the regiment commanded by Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex. In 1620 the brigade took its place alongside other Protestant contingents in the Rhineland. Once the campaigning season had ended Lord Essex returned to England to recruit more men. He repeated the exercise every winter from 1621 to 1624. The Devereux family had property in Staffordshire, and had long enjoyed close friendships with several leading families in the region, not least that of Thomas, Lord Cromwell (a distant cousin of the then obscure Oliver Cromwell). Staffordshire was therefore an obvious place for the Earl of Essex’s recruitment drives. Cibbel Steiphenson declared in her 1651 petition that her husband had served for about thirty years, which suggests that he was one of Lord Essex’s earliest recruits. Francis took part in several campaigns in Germany and the Low Countries. In 1657 Cibbel added to her testimony in declaring that her husband had also served in the Palatinate. This would fit with Vere’s presence there from 1621 to 1623, in support of Frederick, the Prince-Elector Palatine, James I’s son-in-law. Francis Steiphenson may therefore have served in one of Vere’s garrisons in Mannheim, Heidelberg or Frankenthal. These towns were gradually reduced by Catholic Imperial forces, with Frankenthal the last to surrender in 1623. Cibbel Steiphenson’s testimony indicates that Francis had returned to England by 1624. In that year King James commissioned a mercenary, Count Ernst von Mansfeld, to mount an expedition to recover the Palatinate. Thomas, Lord Cromwell was engaged to raise a regiment for Mansfeld’s expeditionary force. Cromwell, who had been created Viscount Lecale by James I, was by now experienced in warfare, having served in Ireland and at sea. The regiment had been intended for the Earl of Essex, and, like Essex before him, Lecale recruited in Staffordshire. The bulk of Mansfeld’s infantry were levies: the Privy Council had instructed provincial magistrates to disburden their counties of ‘unnecessary persons’ by conscripting unemployed males, vagrants and those living ‘lewdly and unprofitably’ [Bodleian MS Firth c. 4, fol. 107]. Turning such men into an efficient fighting force was a job for experienced officers and tough NCOs. Francis Steiphenson was a perfect choice for a sergeant: he was a seasoned soldier, and familiar with the Palatinate. Moreover, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest that recruits tended to accept discipline more readily from officers and NCOs from their own locality. Mansfeld’s expedition was a disaster. His regiments arrived on the Continent in January 1625, but most of the men died of disease, exposure and starvation without ever seeing combat. As a veteran, Francis Steiphenson was more inured to hardship and contagion than the raw recruits. Having survived once again he found employment back in England, as a sergeant in the Staffordshire Trained Bands. His role was probably to instruct the part-time county militia in weapons drill. Cibbel Steiphenson’s declaration that he served under the Earl of Essex for a second time ‘in the north of this kingdom’ is a clear reference to the First Bishops’ War of 1639. Soon after Essex was made Lieutenant-General of Charles I’s infantry, several counties were instructed to lend him companies from their trained bands. Staffordshire sent a contingent, and it seems evident that Sergeant Steiphenson marched north with it. The outbreak of civil war in England in 1642 saw the Earl of Essex appointed Captain-General of Parliament’s forces. Viscount Lecale’s Irish estates had been lost early in the 1641 Rising, but he returned to Ireland to command a regiment of horse for the King. His services there prompted Charles I to elevate him to the earldom of Ardglass in April 1645. Which man did Francis Steiphenson follow? The answer appears to be neither. Cibbel stated in her 1651 petition that her husband had served in Ireland ‘since the beginning of these late and still continuing distractions there’. Assuming that her reference to service ‘in the north of this kingdom’ and a later reference to service in England both refer to the Bishops’ Wars (the Second Bishops’ War being fought mainly in northern England), this would imply that Francis was shipped out in December 1641 with one of the regiments sent to the Earl of Ormond in the Pale of Dublin. He was therefore not technically a parliamentarian until June 1647, when Ormond – worried that he had insufficient forces to protect the Pale from the Catholic Confederacy – handed his troops over to Parliament. Soon after this, Steiphenson was promoted to the rank of lieutenant. The attritional nature of Irish warfare had compounded the officer shortage, and able NCOs were obvious promotion candidates. Lieutenant Steiphenson’s luck ran out at some point around 1650. He was badly wounded, and invalided back to England, arriving in Staffordshire ‘in a languishing condition’. He was awarded an annual pension of 40 shillings per annum by the Staffordshire authorities. This was a common soldier’s pension rather than one befitting an officer, but it must be remembered that Staffordshire’s economy had been crippled by the wars. That said, a year earlier, when Lieutenant William Baggeley of Eccleshall had objected to being awarded a similar pension the county Justices had promptly raised his allowance to £10 per annum [SAH Q/SR/265, fol. 4]. Francis Steiphenson died in the winter of 1650-51. Soon afterwards, his widow heard that their son Edward had been killed in Scotland whilst serving with the New Model. Cibbel promptly petitioned the Staffordshire Bench, to request that the Justices convert her late husband’s meagre allowance into a widow’s pension. She was now old, she said, and having been ‘deprived of the comfort and help both of a husband and son’, she was ‘destitute of subsistence or livelihood’. On the face of things, Cibbel had a strong case: in addition to her husband’s long service, Edward had been steadfastly loyal to Parliament, taking part in the sieges of Chester and Lichfield, as well as other actions. The endorsements on her 1651 petition reveal that was supported by leading inhabitants in the parish of Fradswell. The fact that Wingfield Cromwell had added his signature was perhaps a mixed blessing, for the Commonwealth state considered his father, the Earl of Ardglass, a delinquent, and had fined him for his royalism. For their part, Staffordshire’s Justices had a long list of needy veterans awaiting the next pensioner’s place to fall vacant. Cibbel Steiphenson’s request was refused. Widows often sold their clothes and household goods to survive, or relied on charity from neighbours, relations or parish officials. In extremity some were forced to beg. Cibbel had one last card to play, as she was aware that her late husband was still owed £10 by the State for arrears of pay. She pursued the matter with the Staffordshire Bench, and in October 1652 the Justices agreed to pay Francis’ arrears, in instalments of 10s a quarter. On the face of things, this should have provided Cibbel with a regular income commensurate with the discontinued pension; however, the instalments were not always paid. It was common for the Treasurers for Maimed Soldiers to prioritise the pensions of veterans, and only pay widows if any money was left. One of Cibbel’s petitions preserved in the Quarter Sessions rolls for Michaelmas 1657 [SAH Q/SR/300, fol. 13] had almost certainly been submitted to an earlier sessions. Cibbel complained in this petition that she had received no money for three quarters in a row, and now had nothing to subsist on. The Justices ordered the Treasurer to pay her 30s, and to see that future instalments were paid. However, Cibbel was forced to petition in October 1657, as the payments had lapsed once again. She reminded the Justices that they had agreed to pay her 10s a quarter until the £10 arrears had been settled in full. She had been paid for three quarters, but ‘calling for the last quarter’s payment she was (upon what pretence she knows not) denied it.’ [SAH Q/SR/300, fol. 14] Cibbel pointed out that she had not only lost her husband, but also the son who would have supported her in her old age. The Justices again admitted the default, and endorsed her petition with the order that it should be paid, and she was henceforth to receive 10 shillings every quarter until the arrears had been paid in full. One entry in the Quarter Sessions order book confirms this decision [SAH Q/SO/6, fol. 88r]. Ominously, however, another entry just two pages later states that ‘Sibill Steevenson’ should be given the disputed 30s, ‘but she is to expect no further allowance’ [SAH Q/SO/6, fol. 89v]. ‘Francis Steevenson’ was recorded merely as ‘a soldier in the Parliament’s service, deceased.’ The Justices’ repeated backsliding was in marked contrast to their sympathetic treatment of Lieutenant Baggeley. Despite having secured a pension of £10 per annum Baggeley had lived beyond his means. By January 1657, having become involved in a dubious money-making scheme, he was imprisoned for debt. He wrote from gaol to request that the Staffordshire Justices give him an advance on his usual quarterly payment [SAH Q/SR/297, fol. 12]. This initial appeal fell on deaf ears, but his wife Ann continued to collect his pension. In July 1658 the Bench relented, and authorised an advance payment [SAH Q/SO/6, fols. 67v, 81v, 103v, 104v-105r]. When Baggeley petitioned in October for a further advance, this was also granted [SAH Q/SR 304, fol. 24; Q/SO/6, fol. 109r]. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the Baggeleys received preferential treatment because Francis Steiphenson was a ‘russet-coated’ officer rather than a gentleman. Did it ever occur to Cibbel Steiphenson to petition the Lord Protector directly? Oliver Cromwell is known to have intervened personally in a number of cases, and his fondness for ‘russet-coated’ officers suggests that he would have given her a sympathetic hearing. Further Reading Ian Gentles, ‘The New Model officer corps in 1647: a collective portrait’, Social History, vol. 22, no. 2 (May 1997), pp. 127-144. Andrew Hopper, ‘“Tinker” Fox and the politics of garrison warfare in the West Midlands’, Midland History, vol. 24, no. 1 (1999), pp. 98-113. Andrew Hopper, ‘Social mobility during the English Revolution: the case of Adam Eyre’, Social History, vol. 38, no. 1 (2013), pp. 26-45. D. W. King, ‘Ralph Margery: Cromwell’s russet-coated captain’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, vol. 58, no. 233 (Spring 1980), pp. 48-54.

Read More

‘He valiantly spent his life in the opposition of that grand rebellion’: the war widows of combatants in Ireland

In 1653 Elizabeth Fowler of Halstead, Essex, petitioned the court of quarter sessions at Chelmsford for relief and received a £3 gratuity on account of the death of her husband. John Fowler had fought for Parliament at the battle of Edgehill (October 1642) and subsequently went into service in Ireland, under the command of a ‘Captain Chapman in Major Warner’s regiment’. According to the testimony of a fellow soldier named Samuel Downes, Fowler lost his life in Ireland ‘by a shot before Lough Gur Castle in the county of Limerick’. Lough Gur Castle or Bourchiers Castle, situated about twenty miles south of the city of Limerick, had been built in the late-sixteenth century by Sir George Bourchier. In March 1642 the castle was taken by a group of Irish Catholic rebels led by William Bourke, Lord Castleconnell. Fowler was no doubt killed during a later attempt to recapture the castle, though it is unclear when this took place. [Trinity College Dublin, MS 829, ff. 258r-259v, Deposition of John Pilkington (14/09/1642)]. Elizabeth Fowler was one of many widows who lost their husbands in Ireland during the British and Irish Civil Wars (1641-1653). For these women, petitions were an important means of survival and as such were tailored for the purpose of acquiring financial and material aid. Recent studies on war widows have highlighted the different strategies used in petitions to assist supplicants in attaining relief, such as expressions of loyalty and the language of poverty and helplessness. Five petitions and fourteen payments relating to women who lost their husbands in Ireland are currently available on the project website. For these women narrative tools were essential for receiving aid, due to the difficulties of acquiring proof of their husbands’ death. In England, widows only needed to obtain a certificate from their husband’s commanding officer, stipulating their husband had died in service, to apply for a pension. According to the Act providing for Maimed Soldiers and Widows of Scotland and Ireland (September 1651), however, widows needed a certificate from the senior commander of the army in which their husband served. This was a much more difficult task as these men were typically not local to the widows and were often still in military service. Of the nineteen payments and petitions only two appear to have provided proof of death. The payment to Christian Lesswell of Coggeshall, Essex, suggests that she had ‘proofe’ of her husband’s service in Ireland, entitling her to a pension of 40s per annum. Jane Plat of Denbighshire had also been able to acquire proof in the form of a certificate, but this was only from her husband’s captain, ‘William Wnlockes’. Nevertheless, she received a pension of £3 per annum. The rest of the women were unable to acquire a certificate and therefore did not meet the necessary criteria for a pension. These widows relied upon the narratives of their petitions to elicit sympathy from justices of the peace, with varying degrees of success. Martha Emming of Coggeshall, Essex, lost her husband at the siege of York in 1644 and a son in Ireland. Martha’s petition (1653) drew upon the language of poverty by describing the distress she was suffering as a result of the loss of her male relatives. She emphasised her inability to work due to her advanced age and was subsequently granted a one-off gratuity of 40 s. Jane Hart of Wellington, Somerset, meanwhile, was denied relief from the justices of the peace in 1653. Jane claimed that her husband had been absent in Ireland for three years leaving her and her poor children ‘destitute of any succour or relief’, but without proof of her husband’s death Jane was only entitled to poor relief under the Elizabethan Poor Law. Consequently, it was ordered that Jane should receive 12 d. per week from the parish. Joane Martin of Winchester, Hampshire, was similarly denied a gratuity or pension due to a lack of proof of death. The justices instead ordered that a place of habitation should be provided for her, another measure outlined in the Poor Law. While most petitioning strategies were common amongst war widows, one strategy for attaining relief was unique to the widows of soldiers in Ireland. On 14 October 1651 Elizabeth Tilston of Wrexham, Denbighshire, petitioned the Chief Justice of Chester, Colonel Humfrey Mackeworth, for relief. Elizabeth had lost her husband Valentine Tilson in Ireland, who had been ‘slain by the Irish [illegible] rebels, leaving your poor petitioner with two small children in great want and misery’. Similarly, Margaret Johnson of Halstead, Essex, petitioned the court of quarter sessions for relief having lost her husband in Ireland, where he ‘valiantly spent his life in the opposition of that grand rebellion, leaving your poor petitioner with two small and sickly children to provide for’. These two women drew upon the memory of the Irish rebellion to improve their chances of acquiring a pension. This was a shrewd approach, side-stepping the difficulties of providing details of a soldier’s military service as proof of loyalty. The scant geographical information offered in the petitions and payments supports the idea that many women were uninformed of their husband’s activities overseas. Of the five petitions available, only Elizabeth Fowler mentions an Irish place name, Lough Gur Castle, likely because she was informed of her husband’s death by a fellow soldier. Amongst the payments only two additional place names are mentioned. Ann Owen of Denbighshire claimed her husband died at Galway, while Elizabeth Bridge of Bocking, Essex, claimed her husband died at ‘Cleningo’. By utilising the Irish rebellion, service in Ireland was framed as part of the universal Protestant cause to defeat the forces of the antichrist, a cause which many Parliamentarians identified with strongly. Royalism was regarded by many as having strong links to the Irish rebels. Since the outbreak of the rebellion on the evening of 22 October 1641, suspicions had grown over the King’s involvement in a popish plot to destroy Protestantism. These suspicions were exacerbated on 4 November 1641 with the publication of a false royal commission, which ordered the rebels to reclaim Ireland for the King. Sir Phelim O’Neill, a notable rebel leader, had issued the forgery hoping that the pretence of royal assent would increase support for the rebel cause in Ireland. While members of Parliament and the political elite were likely aware that the document was fake, the association between Charles I, a universal Catholic conspiracy and the Irish rebels was politically advantageous. Consequently, parliamentarians emphasised these links throughout the 1640s, calling upon the memory of the rebellion to show that the royalists had chosen the wrong side. By claiming their husbands had died at the hands of the Irish rebels, war widows were thus able to justify their right to relief by highlighting the loyalty of their husbands to Parliament and the Protestant cause. The evidence so far suggests that utilising the memory of the rebellion was a lucrative strategy for attaining relief. Elizabeth Tilston was given 50s annually out of the county’s collections for maimed soldiers and war widows, an amount which increased to 60s in 1657, while Margret Johnson received a £3 gratuity. As more petitions are added to the site no doubt the extent to which the memory of the Irish rebellion was used as a petitioning strategy and what effect this had on relief will become even more clear, offering a new Irish dimension to the study of war widow petitions. Further reading Imogen Peck, ‘The great unknown: the negotiation and narration of death by English war widows, 1647-60’, Northern History, 53/2 (2016), pp. 220-235. Hannah Worthen, ‘Supplicants and guardians: the petitions of Royalist widows during the Civil Wars and Interregnum, 1642-1660’, Women’s History Review, 26/4 (2017), pp. 528-540. Dr Bethany Marsh is currently the Irish Government Senior Scholar at Hertford College, University of Oxford. Her research explores the lives and experiences of refugees from Ireland in the 1640s and 1650s, with a particular focus on the organisation and dispensation of parish relief in England.

Read More

‘This horrid kinde of cruelty’: narratives from the Irish theatre of the Wars

‘The English Civil Wars’, ‘the Great Rebellion’, ‘the English Revolution’, ‘the British Civil Wars’, ‘the Wars of the Three Kingdoms’. These are all names that have been used to refer to the various conflicts in what we now know as Great Britain and Ireland which occurred in the mid-seventeenth century. The last two terms were created to underline the key role that Ireland and Scotland played in these conflicts. But even the new terms remain contested – ‘British Civil Wars’, for example, creates a similar dispute to that of ‘British Isles’ being used as a shorthand for Great Britain and Ireland. Fortunately, however, the role of Ireland is nowadays rarely forgotten by the scholars of the Wars, even if historiographical debates continue. In this blog, Oresta Mukute, examines how narratives of loss from the Irish theatre of the Wars may be compared with those on Civil War Petitions... It is difficult to see how the Civil Wars in England would have erupted had the Irish Rebellion of 1641 not occurred. Beginning as an attempt at a coup d'état by a few members of Irish Catholic gentry, the Irish Rebellion of 1641 developed into an ethnic conflict between the wider community of Catholic Gaelic Irish and ‘Old English’ on one side, and English, Welsh and Scottish Protestant settlers on the other. The Rebellion immediately precipitated a political crisis in Westminster, as the King and Parliament could not trust each other to control the army which was intended to quell the Irish rebels. It is arguable that had Charles accepted the list of grievances presented to him by Parliament a couple months after the rebellion broke out, the revolt in Ireland may have been settled with relative ease. Instead, however, Charles I mobilised an army of his own, thus officially starting the First Civil War in England. The conflicts of the decade inflicted a huge death-toll on the population of Ireland, with estimates concluding that the loss of life at the time was more significant than that in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, or even the potato famine of the 1840s. In the midst of the tumult, the colonial administration was anxious to provide the Protestant refugees fleeing to Dublin with a framework for compensation and to find a way to acquire intelligence about the insurgents. The surviving collection of the depositions has been digitised and published on the 1641 Depositions website (http://1641.tcd.ie/). Similarly to the Civil Wars Petitions Project, it stores a great deal of very rich information on the events between 1641 and 1653. It contains a digitised collection of about 8,000 statements collected by the Commission for the Despoiled Subject, largely from refugees who fled to Dublin. Unfortunately, no equivalent for losses on the Catholic side exists. As with official documents from all time periods, the form and structure of the depositions were fairly standardised. Typically, after collecting the names, occupations and addresses of the deponents, the commissioners examined what robberies and spoils had been committed, under what circumstances, and to what value; any names of those known to be responsible; any memory of traitorous or disloyal words used by the rebels and any known instances of murder. The factual validity of the depositions has been questioned by historians ever since their collation, due to the 1641 Rebellion swiftly becoming the focus of religious and political propaganda. Nonetheless, these types of documents provide us with rare access to the voices of early modern people, even if these have been mediated by legal processes. They are important personal accounts which have a unique importance because they contain the most detailed information about what happened in Ireland during the decade of conflict. But they also convey the sense of the terror which the violence brought, which we know is also evident in English and Welsh accounts of the Wars. Although women were the smaller group of deponents, Protestant authorities, such as the head of the Commission for the Despoiled Subject, Henry Jones, often chose to include women’s narratives in disproportionate numbers in their descriptions of the events in Ireland. This is likely due to the fact that many female narratives may have been perceived as more emotional and therefore more appropriate for sensationalist reporting. Undeniably, however, the contents of their depositions featured heavily also due to the fact that many of them included descriptions of violence on Protestant women and children. The obligation to protect certain categories of people was understood to be a part of the unwritten laws of nature and Christian morality. In aiming to portray the Catholic Irish rebels as barbarous or otherwise unruly, violence against women, especially the kind that mimics biblical stories, was very useful. ‘This horrid kinde of cruelty’, Sir John Temple wrote in The Irish Rebellion (1646), ‘was principally reserved by these inhumane Monsters for Women, whose sex they neither pitied nor spared’. Although the goal of this post is not to explore violence against women specifically, the special place of women in this conflict is the reason it will compare a female deposition to a similar petition that can be found on the Civil War Petitions website: the deposition of Joane Parker, of County Cavan and the petition of Marie Burton of Stansty, Denbighshire. These documents were chosen for their two key similarities: both narratives were recorded in the late 1640s, and both women were widowed after their husbands died in imprisonment. But there are equally differences to be acknowledged. Firstly, the two documents served different functions. The depositions were originally created in Ireland to record the loss of goods and the activities and alleged crimes of the Irish insurgents. The petitions, meanwhile, were collected when soldiers, widows and orphans wished to claim help from the authorities due to the effects of the Wars on their families. And whereas most Protestant women deposing in Dublin would have witnessed the conflict in their communities, this would have been rarer among the females petitioning in England and Wales (although there are examples of women following army camps, living in garrison towns, or being combatants themselves). It is therefore clear that Joane’s and Marie’s narratives will express and emphasise different things. Joane’s experience of conflict, the way she recalls it, was very direct: some insurgent leaders ‘and a great number of their followers and people entered [her] dwelling house’, seized ‘some arms which the deponent’s said husband kept for the defence of himself and his family’ and carried away their animals and food. She then witnessed her husband being ‘carried by the rebels to Kilmore … as prisoner’, where he died. Joane’s deposition, however, somewhat unusually did not mention violence against her own body—many Irish depositions describe women being stripped of their clothes and being forced to flee their homes. Perhaps Joane did not experience this—if her husband’s imprisonment was the main goal of the rebels, they may not have been interested to humiliate his wife any more. Joane’s deposition claims that her losses added up to over £1200; a small fortune at the time. The wife of a rich yeoman, then, may not have been of interest as a target of further humiliation, as she was already ‘robbed and forcibly despoiled of all her estate’. However, these omissions can often have other causes too, such as the aforementioned fact that these actions were aimed to humiliate the victims. Marie Burton’s experience of conflict, although similar, was expressed in a slightly different way. She stated that her ‘family and estate’ were exposed ‘to the merciless cruelties of the enemy’, but these cruelties were not elaborated on. Whilst this phrase could have described the burden of taxation or free quarter, it was possible that it referred to more violent activities. It is unclear whether Marie experiened them, or whether she simply wished to state her vulnerability after her husband, John, enlisted himself as a soldier and left her and her four small children to fend for themselves. Unlike Joane who was regarded a victim by simply living in Dublin as a refugee who lost many material goods as well as her husband, Marie had to justify this status. Not only did she have to convince the Justices of the Peace in the county of Denbigh that she was in a ‘distressed condition’, but also that her husband was a loyal soldier who promoted ‘the parliament’s service to the utmost of his ability’. But is their experience that different after all? Although Joane, it is implied, witnessed the imprisonment of her husband personally, she, just like Marie—who received news of her husband’s ‘imprisonment, by the cruel and savage usage of the enemy’ and his consequent death—found out about it through someone else. Whether they received the bad news by letter, hearsay or via someone in the community, this aspect helps to level their stories. An interesting detail to note, however, is the fact that Marie’s petition initially said that her husband had been ‘slain’, and that this was crossed out and replaced with ‘dyed’. We cannot know whether Marie corrected this herself upon having the petition read back to her, or whether the scribe was the one who decided the latter word would be more appropriate. Either way, it suggests that whoever made this decision, acknowledged that the husband died in a more passive way as a prisoner, rather than being murdered instantly in a violent event. Additionally, just because Marie did not describe violence perpetrated within her home, does not mean that she, or other women in Wales, did not experience such incidents. If we were to assume that she did not suffer directly at the hands of the enemy, it would not be mistaken to claim she may have witnessed other lone women in Denbighshire faced violence. Marie, therefore, could have used their experiences to justify and explain her own fears. Her petition was submitted during the Second Civil War, and had she not trusted the Justices to be aware of local conflict and violence, it seems unlikely that she would have brought it up as a part of her plea for assistance. Unlike those deposing in Dublin, she was not there to recall events that the authorities were not witnesses to, but rather to fashion herself as a widow in need of help. Many women’s narratives in both the depositions and the petitions reflect not just their own stories, but also the stories of those around them. The aim of this comparison is not to suggest that Joane’s, Marie’s, or any other women’s sufferings were identical in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Rather, this small case study illustrates that there are ways to compare, quite directly, the experiences of certain women (and men) in the Wars, whether they struggled in a conflict at their doorstep, or one farther away. Not many accounts can be compared as fairly, and it is undoubtable that many people deposing in the 1641 Depositions recall atrocities that few (if any) English and Welsh accounts can match. Nonetheless, it shows that narratives of suffering and loss can and should be compared—the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, as historians now acknowledge, were unavoidably and inextricably linked. From this we can assume that there is much scope to begin investigating whether their suffering was linked in the same way. Further Reading The 1641 Depositions Project http://1641.tcd.ie/ Nicholas Canny, Making Ireland British, 1580-1650 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001). Aidan Clarke, ‘1641 Depositions’ in Peter Fox (ed.), Treasures of the Library (Dublin, 1986), pp. 111-22. Imogen Peck, ‘The great unknown: the negotiation and narration of death by English war widows, 1647–1660’, Northern History, 53:2 (2016), pp. 220–35. Oresta Muckute is a first year PhD student at the University of Leicester. She is working on comparing the narratives of loss in Ireland, England, and Wales in the mid-17 century.

Read More

‘Your petitioner having much suffered’ – Petitioners to the Court of Wards during the British Civil Wars

For families, the impact of loss of life during the British Civil Wars often went beyond the emotional and financial. For those who held land as tenants-in-chief of the King, there was the added burden of wardship and the legal processes and expense that it incurred. Widows whose husbands had been slain in battle now had to face a contest of their own as they fought to keep the custody of their children and protect their inheritance against competitors who saw financial profit in obtaining the wardship for themselves. Between 1642 and 1646 this burden was often exacerbated by rivalries within families induced by the conflict. It was also affected by the increased complexity of the legal processes as the Court split, with rival courts at Oxford (for the King) and Westminster (for Parliament). In this blog, Diane Strange uses petitions to the Court of Wards to investigate some of the problems faced by its litigants, as well as how the Wars affected the running of the Court and contributed to its demise in 1646. On 19 November 1645 a petition arrived in front of Viscount Saye and Sele, master of the Court of Wards and Liveries in London. It came from Elizabeth Dawnay, widow of John Dawnay of Cowick, Yorkshire, and daughter of Sir Richard Hutton, the common-law judge who opposed Ship Money during the Personal Rule. Elizabeth explained that her ‘late brother’, the second Sir Richard Hutton, had died about twenty days previously, ‘seized of diuers Mannors and lands in the Countie of York ... leaueing his son & heire within age & in warde to his Ma[jes]tie’. As Ronald Hutton relates in his blog post Meet a magistrate, Sir Richard had fought valiantly for the King up to his death in battle at Sherburn-in-Elmet on 15 October 1645. The object of Elizabeth’s petition was the third Richard Hutton, Sir Richard’s son who, we are glad to learn from Ronald Hutton, survived the war and its aftermath and at last ‘lived out ... his days in peace.’ As Elizabeth went on rather breathlessly to explain, she had learned that Sir John Savile, a distant relative of the ward, had petitioned the Court already for young Richard’s wardship, ‘upon some p[re]tence of Alliance to the ward’. With a strength of will of which we hope her father would have been proud, Elizabeth asked for a supersedeas, a writ that would override Savile’s suit, and for permission to pursue the wardship herself, effectively ousting Savile from the case [TNA WARD 10/39part1]. Such competitions were common, since wardships could be lucrative and offered inviting scope for playing out feuds and family rivalries through the battle for the child – or children, where there were female coheirs. But this case had uncomfortable undertones. For whereas Hutton had died fighting for the Royalists, Savile was a Parliamentarian colonel in the northern army under Ferdinando Lord Fairfax. This, then, was a war within a war: the battle for custody of Richard and his estate between adherents to rival sides. Nevertheless, as Elizabeth had rushed her petition into Court just within the month allowed to relatives to prioritise their claim over other potential guardians, the staunchly Parliamentarian Saye authorised the supersedeas (perhaps with a sigh) and granted Elizabeth the writ that she sought. Elizabeth Dawnay’s anxious petition is just one of thousands to the Court that survive in The National Archives at Kew. They originate from all sorts of people, from nobility boasting thousands of acres of land, through the gentry, and down to the poorer sort with just a small tenement an acre or two worth no more than a few pence per annum. Almost all of them held their land from the king ‘in capite by knights service’, meaning that if upon the death of the tenant the heir was a minor – 21 for a boy, 14 for a girl – they were liable for a wardship, which embarked their family on a prolonged and costly legal process. ‘Knights service’ had once meant fighting for the king in defence of the kingdom in return for the grant of royal land. If the tenant was a minor, then they became a ‘ward of court’ until they came of age, giving the Crown the right to their marriage and the lease of their lands. The custom of obligatory military service was long defunct by the seventeenth century; instead, recompense for living on the royal demesne took the form of a fine, levied through the sale of ‘the wardship of the body and lands’ as the petitions frequently term it, and the right to arrange his or her marriage. Thankfully, the morality or otherwise of this need not trouble us here. Instead, the focus is on the petitions as historical documents and the shaft of light they shine on the hidden effects of the Civil Wars: the fate of the widows and children of the slain, and their lands. In its rawest state, a petition to a court of law was a simple initiation of a legal process: it advised the court of the matter at issue and set the business in motion. So Elizabeth Dawney, in common with thousands of petitioners like her, summarised what had happened and then stated, in suitably humble terms, what she desired. In most cases the petitioners were reporting that a death had occurred and that there was a tenure for the king, and they were asking to compound for the wardship of the heir. But hanging on this bare framework is a wealth of detail that gives us fascinating and often illuminating insights into the politics, society, economics and land distribution of the age. Like Elizabeth Dawnay’s, every petition tells a story. Each has its cast of characters with hopes, prejudices, rivalries or anxieties. A few evince a plot. Sometimes there is a heroine, but rarely is there a hero, and often we encounter a villain. Underpinning each story is a plethora of detail and information about the aspirations and disappointments of an incredibly diverse spread of humanity, and each one is indicative, in some microcosmic form, of what it meant to be human in early modern England. They represent a part of what Diarmaid MacCulloch has termed ‘the flotsam from a host of individual stories of human beings’, unlikely survivals of what over the centuries has been the widespread and often unwitting destruction of a morass of manuscript material. Individually, each petition contributes to a corner of historical knowledge; en masse, they help to emphasise how deeply embedded wardship was in early modern law, society and economy, and offer intriguing hints at why the wardship system escaped abolition for so long. The British Civil Wars witnessed the twilight and final closure of the Court, and as the petitions illustrate, the problems of wardship and the covetousness of the officials who perpetuated it, set down in The Grand Remonstrance of 1641, were exacerbated by the pressures of war and the rivalry that ensued as both sides fought for control. In a royal proclamation dated 27 December 1642, and much to Parliament’s chagrin, the King announced the removal of the Court of Wards to Oxford. Unyielding despite Parliament’s petition to let it remain at Westminster, Charles ordered its personnel to move with him, including Saye, who had replaced Lord Cottington as master during the King’s reshuffle of offices in April 1641. Not all were obedient to Charles’s will. Twelve Court officers refused the move, as did two local officials: ‘Geruase ffeodary of South[amp]ton’, and Thomas Goodyere, the feodary of Gloucestershire, denounced in a strong hand as ‘an Arch Rebell’. [BL Egerton 2978, f. 76]. Unsurprisingly Saye too refused to accompany Charles, and by order of the Lords remained at Westminster. Thus there was a ‘curious paradox’ as historian of the Court H.E. Bell wrote, ‘when the men who had consistently opposed wardship and livery themselves maintained their own Court of Wards and Liveries’. What previously few on either side had wanted, now both sides wanted: control of the wardship machine. Petitioners to the Court of Wards now faced a choice. Did they start process through the King’s Court, or Parliament’s? For many, it would have been an obvious choice; for others it would have been a traumatic decision. The fate of their children, their lands, their finances and their lineage might rest on the outcome. Insights into how people made that choice are still hazy. Few petitions to the Oxford Court have yet emerged, so it is not possible to compare the operation of the Courts through their petitioners or to determine how individuals made their choices. Logically, Royalists would be expected to petition the Oxford Court, with Parliamentarians petitioning Westminster. Yet the evidence suggests it was not that clear cut. Elizabeth Dawnay petitioned Lord Saye despite her royalism, but as Sir John Savile had initiated the business through the Westminster Court she might have felt obliged to pursue that course. What the petitions suggest, however, is that some Royalists petitioned the Westminster Court voluntarily. Dame Elizabeth Hewett petitioned in 1644 for the wardship of her grandson, 17-year-old Thomas Richardson, the son of Lord Chief Justice Sir Thomas Richardson, a Royalist supporter who died in prison in Norwich in 1644. Also in 1644, Richard Foxley petitioned for the wardship of Newdigate Poyntz’s son; Poyntz was killed while fighting for the King at the battle of Gainsborough, which took place on 28 July 1643. We also find Lady Anne Harcourt petitioning the Court on 30 December 1645. Lady Anne was the widow of the Royalist Sir Simon Harcourt, who died fighting Irish rebels three years earlier, in 1642 [WARD 10/42part2]. It is nonetheless noteworthy that Lady Anne was still seeking a writ in 1645, three years after her husband’s death. Lady Anne’s case may suggest that Saye was unwilling to prioritise the suit of someone who had been shown open favour by the King. Charles had lauded Sir Simon for his service in Ireland following news of his death and had rewarded him posthumously: ‘after “much bewayling the losse” of Sir Simon, the King granted the forfeited lands and castle where Sir Simon had fallen to Harcourt’s widow and children.’ Saye, perhaps, felt little incentive to assist the widow of a fêted Royalist. Royalists might have made this choice because they found it hard to break with legal tradition or because they doubted the credentials of the breakaway Court. Or possibly the long-established Westminster Court was deemed to function more effectively than its Oxford rival. Bell, who has conducted some of the only research into the bifurcated nature of Court during the Civil Wars, was left with the impression ‘that the scope of the Oxford Court was limited’. Did any cases where there were rival competitors to the wardship, such as that of Elizabeth Dawney and Sir John Savile, involve petitions to both Courts, with rival claimants in each? It seems likely: but so far the evidence is lacking. What can be suggested, however, is that the Oxford Court was less well organised than the Westminster Court, not least because it lacked its Master. In the early months of the conflict Cottington was lying low at his house in Fonthill Gifford, Wiltshire, and did not join the King at Oxford until April 1643. In his absence, petitions were being handled by Charles’s secretary Sir Edward Walker, and by Richard Chamberlain, clerk of the Court, and some at least were overseen by Charles himself. [BL Egerton 2978, f. 87] The problems of running a court in wartime were not limited to Oxford. During the 1640s the Court began to witness a rapid rise in a form of petition rarely seen in earlier decades: prompts for the Master to appoint a date for a hearing. A slackening of business due to the difficulties of the times is evident from mid-1642. Margery Caesar, the guardian of John Caesar, a ward, petitioned on 15 June 1642 asking for a hearing; a month later, Roger Bodenham saw fit to reminded the Court that the depositions relating to his case had been published, ‘and the Cause [is] ready for hearing as by y[ou]r ord[e]r hereunto annexed may appear’. The widow Jane Dockwray, a defendant, also petitioned in 1642 asking for a hearing, reminding Saye that the case was ‘Ripe for yo[u]r Lor[dshi]pps Judgm[en]t’ [WARD 10/42part2]. Many more petitions tell a similar story of cases delayed or postponed and suggest that even before the split, the Court was experiencing difficulties in coping as the crisis unfolded. As the conflict developed, petitioners also found it difficult to pursue their cases due to the upheavals of war. Elizabeth Bewicke first petitioned for the wardship of her son in April 1642. She petitioned again in June, pleading for further time to find the office because of the absence of the necessary commissioners ‘beinge att London aboute business in parliam[ent]’. ‘The great destracc[i]ons of the times’ prevented Elizabeth Spitty from prosecuting her case in May 1644, while due to the plunder of Sir Edward Peyto’s house and the removal of the evidences late in 1645, Devereaux Peyto and James Prescott were hampered in their wardship bid. They, too, sought a grant of further time [WARD 10/39part1]. What many of these petitioners never got was any form of closure. Neither Elizabeth Dawnay nor Sir John Savile nor the persistent Dame Anne Harcourt could expect an official resolution to their fights, as the Court of Wards was formally abolished by the Long Parliament on 24 February 1646. In the following July the royal seal was brought from Oxford to London and broken. For many, the abolition came not a day too soon. Feudal tenures had long been thought on as an anachronism, a relic of dead times, an uncomfortable survival of pre-Reformation ideologies and honour values that had no place in the sensitive Protestant milieu of early modern England and Wales. Men no longer performed military service in return for land; family values were changing and the child was deemed to belong with the mother in the family home, not to be farmed out at the Court’s discretion. Feudal tenures had become an exploitative system of revenue generation, a tax on land – and no one loves a tax. Speaking at a conference of the Lords and Commons back in March 1610, the Earl of Salisbury had expressed the importance of wardship to the king in a rather strained metaphor, volunteering that it was ‘not a leaf but a bough and arm of ... a great tree in his garland’. Now the great limb had been struck from the royal garland and few were sorry to see it go. Especially glad, no doubt, were the thousands of petitioners for whom the stress of wardship and its associated litigation had been added to the tragedy and loss inflicted on them by the British Civil Wars. Further Reading E. Bell, An introduction to the history and records of the Court of Wards & Liveries (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953), pp. 150–153. Richard Cust, Charles I and the aristocracy, 1625–1642 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 232. Mark Charles Fissell, English Warfare, 1511–1642, 2nd edition (Oxford: Routledge, 2016 [First edition 1991]), p. 281. Elizabeth Read Foster (ed.), Proceedings in Parliament 1610, Vol. I: House of Lords (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1966), p. 25. Martin J. Havran, Caroline courtier: the life of Lord Cottington, (London: Macmillan, 1973), p. 159. Diarmaid MacCulloch, A history of Christianity, 2nd edition (London: Penguin, 2010), p. 11. Diane Strange is an M4C AHRC-funded PhD student at the University of Leicester. Her research focuses on petitions and petitioning strategies to the Court of Wards and Liveries between 1610 and 1645. She is currently developing her research into petitions to the Court of Wards during the British Civil Wars into a journal article, which she hopes to publish in 2021. Diane is the author of ‘From Private Sin to Public Shame: Sir John Digby and the use of Star Chamber in Northamptonshire and Bedfordshire, 1610’, Midland History, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Spring 2019), pp. 39–55, which won the Midland History Essay Prize in 2018. She is also the co-editor of the brochure for ‘The World Turned Upside Down’ exhibition at the National Civil War Centre.

Read More

Margaret Nightingale: War Widow – and Witch?

In recent years historians have become increasingly interested in the occult dimension of the English Civil War: in the attempts which were made by Parliamentarian and Royalist propagandists to capitalise on the contemporary fear of witches, and in the ways in which that fear manifested itself on the ground during the conflict - most notoriously, perhaps, during the terrible witch-hunt which broke out in Parliamentarian-controlled East Anglia in 1645, under the direction of the self-styled ‘Witchfinder General’, Matthew Hopkins. It is well known that the great majority of those who were prosecuted as witches in early modern England were women, and that, of these women, a high proportion were widows. Hopkins’s very first victim, indeed, was Elizabeth Clarke: a one-legged widow from Manningtree, in Essex, who was hanged at Chelmsford for witchcraft in July 1645. There is nothing to indicate that Clarke’s deceased husband had been a soldier - but recent research for the ‘Conflict, Welfare and Memory’ project has uncovered evidence which suggests that at least one seventeenth-century Englishwoman did suffer the devastating twin blows of first seeing her husband slain as a soldier during the Civil War and, then, many years later, undergoing prosecution as a witch. This blog-post, by Mark Stoyle, tells her story... In April 1661, almost a year after the Restoration of Charles II, the justices of the peace of the city and county of Exeter - the regional capital of South West England and then one of the kingdom’s largest urban communities - assembled at the Guildhall in order to sit as magistrates at the Easter meeting of the city’s quarter sessions court. With their judicial duties discharged, the JPs then turned to consider the annual rate which was levied on the nineteen city parishes for the support of the poor and, having set the amount for the following year, went on to direct that a large proportion of the monies raised should be spent, as usual, on providing relief for three specific groups of local ‘paupers’: the prisoners in the town gaol; the residents of the alms-houses at St Anne’s Chapel, in the suburban parish of St Sidwell’s, and the residents of St Katherine’s alms-houses, near the Cathedral. Yet, on this particular occasion, the JPs departed from their normal practice by identifying a fourth group of indigent persons whom they deemed to be worthy of the citizens’ collective charity and by ordering that ‘the residue’ of the monies raised from the rate should be paid ‘to the maymed souldiers [of this city] as the Justices … shall … direct’. Having recorded the JPs’ instruction in the quarter session order book, the clerk of the court then listed at the bottom of the page the names of nine men - four of them inhabitants of St Sidwell’s, and one of them a resident of St Katherine’s alms-house - all of whom, he noted, were from henceforth to be paid pensions of between £1 10 s. and £3 a year. We know for certain that one of the maimed soldiers who was supported by the rate had been wounded while serving in the Royalist army during the Civil War, and it seems highly likely that most, if not all, of the others had been too. The JPs’ order of April 1661 thus suggests that, in Exeter - as in several other English counties - magistrates had begun to award pensions to ex-Royalist soldiers who had been injured and had consequently fallen on hard times even before they had been specifically enjoined to do so in the Act ‘for the releife of poore and maimed … souldiers who have faithfully served his majesty and his royal father in the late wars’ which was to be passed by the so-called ‘Cavalier Parliament’ during the following year. As well as instructing JPs to arrange for the provision of pensions to former soldiers who had been injured while fighting for Charles I, the Act of 1662 also instructed them to provide unspecified forms of financial relief to ‘the Widowes … of such as have died … in the said service’. The inclusion of this latter clause in the Act almost certainly explains why, when the JPs next met to review the poor rate, in April 1662, they ordered that pensions should be paid, not only to ten maimed soldiers living within the county and city of Exeter, but to two soldiers’ widows as well. About the first of these women, a certain ‘Barbara Slooman’, little further evidence survives. The value of the pension awarded to her was left blank by the clerk of the court in 1662, but in subsequent years she enjoyed an annual stipend of £1 10 s. The second female recipient of the magistrates’ bounty was ‘Margarett Knightingall, widow’, under whose name the clerk scribbled the three additional words ‘her husband slayne’, meaning, presumably, that Nightingale’s husband had been killed while serving as a Royalist soldier during the Civil War. For reasons which remain unclear, Nightingale was awarded a slightly larger pension than Slooman: a stipend of £2 a year. This was a respectable sum - especially as post-Restoration JPs were far more likely to palm-off Royalist soldiers’ widows with a one-off gratuity of a few shillings than to award them a regular pension of the type which Slooman and Nightingale had secured. This atypical generosity becomes all the more surprising when we consider that, less than a year before Margaret Nightingale was awarded a widow’s pension by the Exeter magistrates, she had been tried before those same magistrates as a suspected witch. Nightingale had initially been denounced to the civic authorities in June 1661, after Maria Knowsley - the infant daughter of William Knowsley, a baker of Holy Trinity parish - had been ‘violently taken in fitts’. Desperate to find out what was wrong with his child, Knowsley had sought an acquaintance’s advice, only to receive the chilling assurance ‘that the said child was bewitched by some person’. Upon hearing these words, the terrified Knowsley had at once recalled that, at the time when Marie had first gone into convulsions, ‘one Margaret Knightingall of … [Exeter], widowe, was then in his house who hath beene formerlie convicted for witchcrafts & inchantments’. Knowsley had promptly rushed to inform the mayor of Exeter - who was also one of the JPs - of his suspicions: assuring him that he ‘verilie beleiveth that the said Margarett Knightingall did practice on his childe & is [the] cause of its distemper’, and adding, as further proof of his claim, ‘that the childe hath beene taken in such fitts [several times] since att the sight of the said Margaret Knightingall’. Knowsley’s accusation had clearly been taken extremely seriously by the mayor and by his fellow-magistrates - all the more so as the unfortunate child had died soon afterwards - and in September 1661 Margaret Nightingale had accordingly been brought before the sessions court at the Guildhall and charged with having murdered Maria Knowsley through the exercise of ‘witchcrafts, inchantments, charmes and sorceries’. Had Nightingale been found guilty on this charge, she could well have been sentenced to death by hanging, as so many other supposed ‘witches’ had been in England over the course of the preceding century. Yet, by the time of the Restoration, judicial scepticism about the possibility of proving, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that the supernatural ‘crime’ of witchcraft had really been committed was beginning to grow. It may well have been partly as a result of this shifting intellectual climate that the trial jury, or the judge - or possibly both - had eventually concluded that Nightingale was not guilty of bewitching the dead child, and the widow had been permitted to go free. How can we explain the fact that Margaret Nightingale, a woman whom we know for certain to have been indicted for witchcraft at the Exeter sessions court in September 1661 - and whom we may strongly suspect, on the basis of William Knowsley’s testimony, to have been actually convicted of that same offence on a previous, unspecified, occasion - should have been awarded a widow’s pension by the town magistrates just seven months later: this at a time when the granting of financial relief to both maimed soldiers and their widows tended to depend not only on those individuals’ wartime conduct but also on their social reputations? The sheer size of Exeter’s population - well over 12,000 people in 1662 - makes it hard to believe that Nightingale and Slooman were the only Royalist soldiers’ widows in the city and had therefore been chosen as the lucky recipients of pensions on that basis alone. It also seems unlikely - though not, perhaps, impossible - that Nightingale had a personal connection with one of the justices. Is it conceivable, then, that the decision to award Nightingale a pension was the result of some sort of politico-religious tussle within the city’s ruling elite? Could members of Exeter’s powerful puritan/non-conformist faction have chosen to encourage, or even to orchestrate, the prosecution of an ex-Royalist soldier’s wife as a witch? And could a majority group of Anglican/Royalist JPs on the bench have then chosen to celebrate Nightingale’s acquittal - and to thumb their noses as their discomfited rivals - by awarding her an annual stipend? Or is the most likely reason that this reputed ‘witch’ was granted a pension simply that she was even more wretchedly poor than were the other Royalist soldiers’ widows who were scratching out a living in post-Restoration Exeter? Whatever the true circumstances may have been, the story of Margaret Nightingale reminds us that, while, in many ways, the experiences of the men and women who lived through the English Civil War exhibit clear parallels with those of individuals who have lived through much more recent conflicts, in other respects, the experiences of mid-seventeenth-century combatants and their families now seem almost impossibly remote. Further Reading M. Gaskill, Witchfinders: A Seventeenth Century English Tragedy (London, 2005). S. Beale, ‘Military Welfare in the Midland Counties during and after the British Civil Wars, 1642-1700’, Midland History, 45 (2020), pp. 1-18. M. Stoyle, ‘Witchcraft in Exeter: The Cases of Bridget Wotton and Margaret Nightingale’ (forthcoming in Devon and Cornwall Notes and Queries, 2020).

Read More

The Case for Universal Access and Design: The Example of the Civil War Petitions Project